Editorial Note on the Apkallu and the Roadmap Ahead

I am breaking the narrative stream to speak directly to the process emerging from our reading on the apkallū, the antediluvian and postdiluvian sages of ancient Mesopotamia.

If you are reading along over my shoulder, you noticed that we digressed from Martin Lang, “Mesopotamian Early History and the Flood Story,” in a post titled On the Date of the Flood.

Martin Lang wrote:

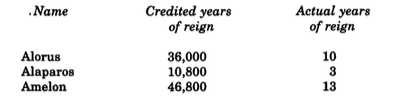

“Berossos’ own knowledge of primordial kings probably goes back to sources that were available in Hellenistic times. The Sumerian King List itself was still known in the Seleucid era, or rather versions of king lists that echo, structurally and stylistically, their ancient forerunners from the early second millennium.

In matching up the primordial kings with the seven sages, the apkallū, Berossos once again works in the vein of contemporary scholars, who demonstrably constructed lists with kings and apkallū in order to advertise their own importance, and the primordial roots of their knowledge, as Alan Lenzi has recently shown.”

I updated that post to include a link to Alan Lenzi, “The Uruk List of Kings and Sages and Late Mesopotamian Scholarship,” JANER 8.2, 2008, which is serialized and linked in posts below.

I also changed the link to the Sumerian King List to point to the beautiful 1939 edition by Thorkild Jacobsen generously published by the University of Chicago Press, available for free download off the web.

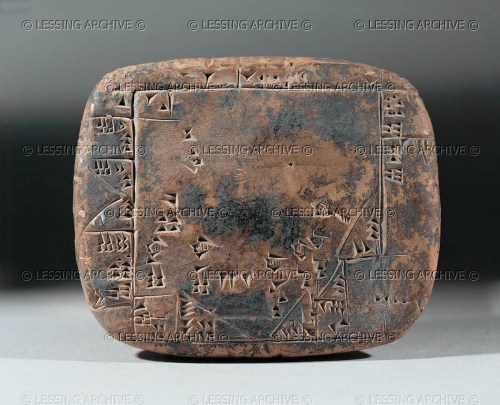

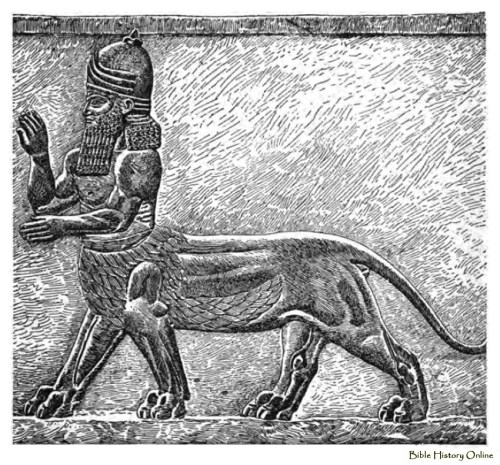

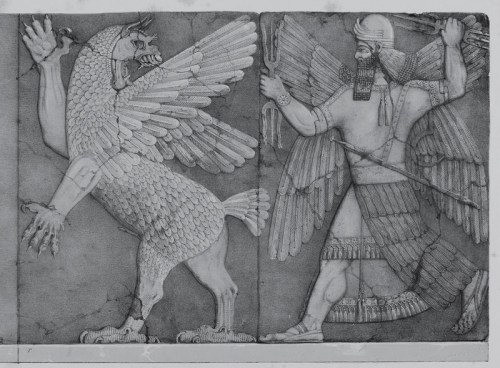

We then dipped into Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, “The Mesopotamian Counterparts of the Biblical Nephilim,” in Francis I. Andersen, et al, eds., Perspectives on Language and Text: Essays and Poems in Honor of Francis I. Andersen’s Sixtieth Birthday, 1985, in a post titled On the Apkallū.

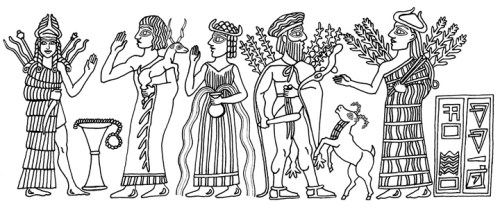

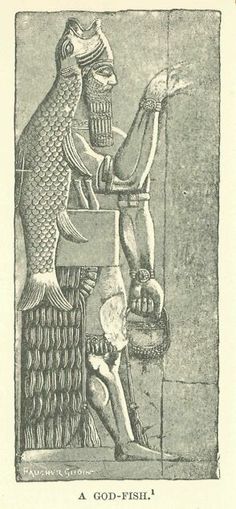

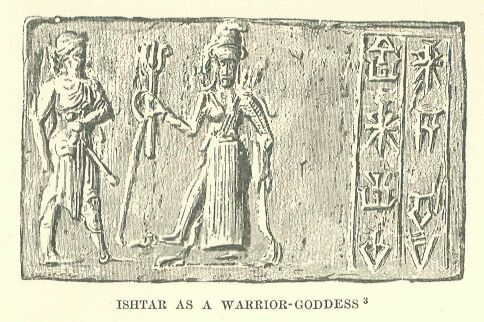

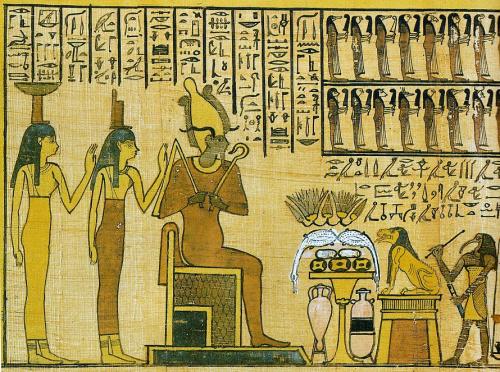

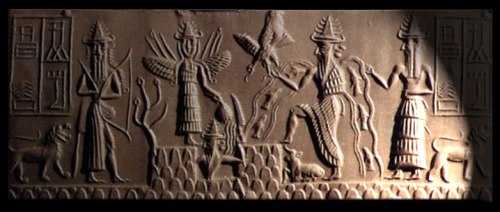

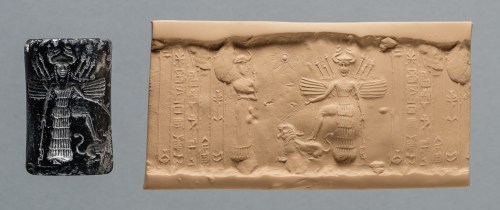

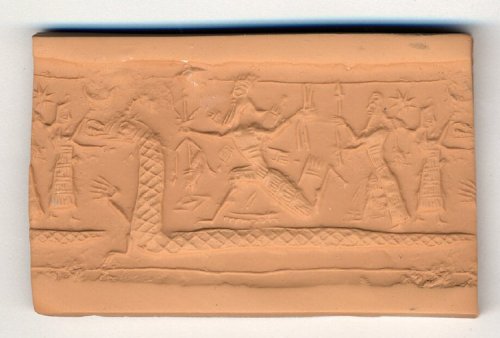

This is where I drilled in hard on the apkallū, incorporating bas reliefs and figurines held at the Louvre and the British Museum. Out of numerous posts addressing the apkallū, this one is well-illustrated, and lushly hyperlinked.

Moreover, Anne Kilmer synthesized the supporting research on the apkallū at the time of writing very effectively, so if you are overwhelmed by the other articles, just read this one. It goes without saying that you should not be intimidated by this academic literature. I have made it as readable and accessible as I can.

Yes, there is a lot of it. As I excavate the academic literature on the apkallū the hard way, mining references from footnote after footnote, I get a sense of what it might be like, to be an academic Assyriologist rather than an autodidact.

I do not include everything that I find. I assess and include just those pieces which accrue gravitas in that greater academic community. If you see glaring omissions, please let me know. This note is shaping up to be an academic survey of the literature on the apkallū, and it may save others treading these same paths some time.

Fair warning: our continuing digression into the apkallu will be deep.

As I complete serialization of source texts, I will include links to the posts beneath their citation below. These sources are sorted by date, so we can track the evolution of academic thinking on the apkallū. Our digression includes excerpts from:

- Erica Reiner, “The Etiological Myth of the “Seven Sages,” Orientalia, v. 30, No. 1, 1961, pp. 1-11. Posted as:

- Anthony Green, “Neo-Assyrian Apotropaic Figures,” Iraq, Vol. 45, 1983.

- Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, “The Mesopotamian Counterparts of the Biblical Nephilim,” in Francis I. Andersen, Edgar W. Conrad, & Edward G. Newing, eds., Perspectives on Language and Text: Essays and Poems in Honor of Francis I. Andersen’s Sixtieth Birthday, 1985, posted as:

- H.S. Kvanvig, Roots of Apocalyptic: The Mesopotamian Background of the Enoch Figure and the Son of Man, WMANT 61, 1988.

- E. Noort, “The Stories of the Great Flood: Notes on Genesis 6:5-9:17 in its Context of the Ancient Near East,” in F. Garcia Martinez and G.P. Luttikhuizen, eds., Interpretations of the Flood, 1988.

- Jean Bottéro, Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop (translators); Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- F.A.M. Wiggermann, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts, Brill, 1992. Posted as:

- Lahmu, “The Hairy One,” is Not Apkallu.

- Mesopotamian Apotropaic Gods and Monsters.

- Apkallu Details (Excerpt from Wiggermann).

- Statues in Private Rooms, the apkallū, “Sages.”

- On the Banduddū, or “Bucket.”

- On the Mullilu, the “cleaner,” the Purification Instrument of the Apkallū Exorcist.

- Things that Apkallū Hold.

- On the Names of the Ūmu-Apkallū.

- Bird-Apkallū, Characterized as Griffin Demons.

- On the Fish-Apkallū.

- Wiggermann Defines the Lamassu.

- F.A.M. Wiggermann, “Mischwesen A,” Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie (RlA) 8, Berlin, 1993-7.

- Anthony Green, “Mischwesen B,” Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie (RlA) 8, Berlin, 1993-7.

- Rykele Borger, “The Incantation Series Bīt Mēseri and Enoch’s Ascension to Heaven,” in I Studied Inscriptions from Before the Flood: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11 (ed. R.S. Hess and D.T. Tsumura; Sources for Biblical and Theological Study 4, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994), pp. 224-33.

- Schlomo Izre’el, Adapa and the South Wind: Language Has the Power of Life and Death, Eisenbrauns, 2001.

- Carolyn Nakamura, “Dedicating Magic: Neo-Assyrian Apotropaic Figurines and the Protection of Aššur,” World Archeology, 2004.

- Ronald Hendel, “The Nephilim Were on the Earth: Genesis 6:1-4 and its Ancient Near Eastern Context,” in Christoph Auffarth and Loren T. Stuckenbruck, eds., The Fall of the Angels, Brill, 2004, posted as:

- Carolyn Nakamura, “Mastering matters: magical sense and apotropaic figurine worlds of Neo-Assyria,” Archaeologies of materiality (2005): 18-45.

- Carolyn Nakamura on the Figurines.

- Nakamura: Rimbaud’s Derangement of All the Senses, Magic, and Archeology.

- Nakamura: More on Magic and Archeology.

- Nakamura: Magic Produces Wonder.

- Nakamura: Magic as Mimesis in Mesopotamia.

- Nakamura: Magic’s Perception and Performance.

- Nakamura: Clay Pit Ritual.

- Nakamura: The Common Terrain Shared by Myth and Iconography.

- Nakamura: An Idiom of Protection Arises in the Material Enactment of Memory.

- Nakamura: Humans Make Up the gods Who Make Them.

- Nakamura: The Figurines as Magical Objects.

- Nakamura: The āšipu was Master of the Figurines.

- Nakamura: Magic Enchants Us with the Possible Made Real.

- Alan Lenzi, “The Uruk List of Kings and Sages and Late Mesopotamian Scholarship,” JANER 8.2, 2008.

- Lenzi: The Uruk List of Kings and Sages.

- Lenzi: The Mythology of Scribal Succession.

- Lenzi: On the apkallū-ummânū Association.

- Lenzi: Human Apkallū are a Later Inclusion.

- Lenzi: A Fault Line Where Legend and History Collides.

- Lenzi: The Apkallū and the Ummânū May Be Artificially Related.

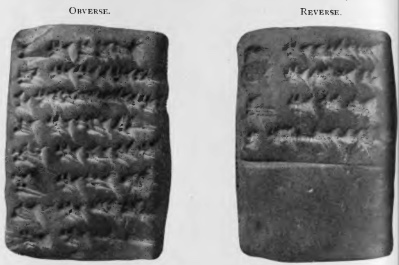

- Lenzi: The Antediluvian Medical Tablet from Ashurbanipal’s Library (K.4023).

- Lenzi: The ummânū Were The Scribal Heirs of the Antediluvian Sages.

- Lenzi: Strabo, Pausanias and Pliny All Have Agendas.

- Lenzi: On the Restoration of the Temples.

- Lenzi: On Nikarchos and Kephalon.

- Lenzi: The Exaltation of the god Anu.

- Lenzi: More on the Exaltation of the Anu Cult.

- Lenzi: Authority Rooted in Divinity.

- Lenzi: The Uruk List of Kings and Sages Renewed the Anu Cult.

- David P. Melvin, “Divine Mediation and the Rise of Civilization in Mesopotamian Literature and in Genesis 1-11,” The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, v. 10, art. 17, 2010.

- Melvin: Origins of Human Civilization–Divine Mediation or Human Endeavor?

- Melvin: Divine or Semi-Divine Intermediaries.

- Melvin: On the Role of Divine Counsel.

- Melvin: Human Civilization is a Gift of the gods.

- Melvin: Who Built the First City? Cain? Enoch? Chouser? Or Nimrod?

- Melvin: On the Tower of Babel.

- Melvin: Divine Instruction Reappears in 1 Enoch.

- Melvin: Divine Knowledge was Sexual Knowledge.

- Melvin: Divine Knowledge is Transcendent.

- Melvin: Human Knowledge is Sinful.

- Trevor Curnow, Wisdom in the Ancient World, Bloomsbury, 2010.

- Stephanie Dalley, “Apkallu,” Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East (IDD), Swiss National Science Foundation, University of Zurich, 2011 (text updated 2011 and illustrations updated 2007).

- Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011.

- Kvanvig: The Lists of the Seven Apkallus.

- Kvanvig: The Apkallu List From Bīt Mēseri.

- Kvanvig: Discrepancies Between the Lists.

- Kvanvig: Introducing Ahiqar.

- Kvanvig: Berossos and Primeval History.

- Kvanvig: Introducing the Apkallu Odakon.

- Kvanvig: The Apkallus Had a Cosmic Function.

- Kvanvig: Bīt Mēseri and the Adapa Myth.

- Kvanvig: The Adapa Myth Symbolizes the Initiation of Humanity into Civilization.

- Kvanvig: Adapa Breaks the Wing of the South Wind.

- Kvanvig: On the Destiny of Adapa.

- Kvanvig: The Apkallu are on the Borderline Between the Human and the Divine.

- Kvanvig: Human Knowledge is Dangerous to the Cosmic Order.

- Kvanvig: Limitations of Human Wisdom and the Loss of Eternal Life.

- Kvanvig: The Apkallus as Protective Spirits.

- Kvanvig: The Bīt Mēseri Ritual.

- Kvanvig: On Sēp lemutti, Averting Evil.

- Kvanvig: The ilū mušīti Are the Stars of the Night.

- Kvanvig: The Maklû Ritual Against Witchcraft.

- Kvanvig: The mīs pî and pīt pî Rituals of Mouth Washing and Mouth Opening.

- Kvanvig: Aššurbanipal Studied Inscriptions on Stone From Before the Flood.

- Kvanvig: Surpassing the Wisdom of the Abyss–Or Not.

- Kvanvig: Five Specialties of Sages Communicating with the Divine.

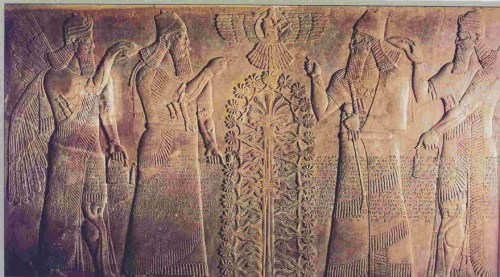

- Kvanvig: The Sacred Tree.

- Kvanvig: The apkallus as Watchers and Guardians.

- Kvanvig: Transmission of Antediluvian Revelation.

- Kvanvig: Antediluvian Scribes of the gods.

- Kvanvig: Initiation is a Restriction of Marduk.

- Kvanvig: Divine Origin of Antediluvian Texts.

- Kvanvig: On the Correspondences Between Antediluvian Myths.

- Kvanvig: At the Brink of Legendary Time and Historical Time.

- Kvanvig: Earthly Counterparts of the Divine Watchers.

- Kvanvig: Dates the apkallu to the Beginning of the 1st Millennium BCE.

- Gebhard J. Selz, “Of Heroes and Sages–Considerations of the Early Mesopotamian Background of Some Enochic Traditions,” in Armin Lange, et al, The Dead Sea Scrolls in Context, v. 2, Brill, 2011.

- Selz: Enoch Derives from 3d Millennium BCE Mesopotamia.

- Selz: On Giants.

- Selz: An Excerpt from the Book of Giants.

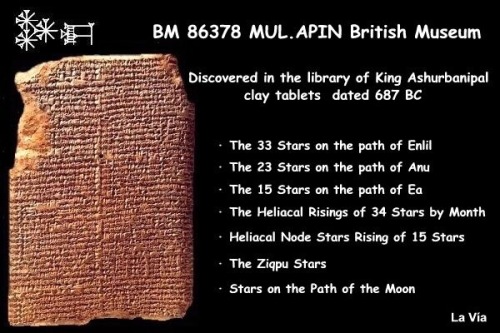

- Selz: Enūma Anu Enlil and MUL.APIN.

- Selz: On the Astronomical Diaries of Babylon.

- Selz: The Debate Over Mesopotamian Influence on Jewish Pre-History is 2000 Years Old.

- Selz: No Connection Between the Biblical Patriarchs and the Babylonian Antediluvian Kings.

- Selz: Tracking Gilgamesh Throughout History and Literature.

- Selz: Patriarchs and Sages.

- Selz: Connects the Apkallu with the Fallen Angels.

- Selz: On Sacred Marriage.

- Selz: Victory Steles, Dreams and the Erra Epic.

- Selz: The Dream of Gudea.

- Selz: Plant of Life or Plant of Birth in the Etana Legend?

- Constance Ellen Gane, Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, University of California, 2012.

After we complete our deep dive into the apkallu, we will return to the Sumerian King List, then resume with Berossos. This is the roadmap ahead.

Editorial note: In some cases citations above which are not followed by links in the bulleted list are internet dry holes, no digital versions are available. In other cases, links are to Google Books editions, which often limit visible pages. Google’s intent is to sell electronic versions of the texts that they scan.

Under these circumstances, I end up rekeying entire articles, at ruinous waste of time. If you have a moment, please send a sweet nastygram to Google asking them to post free and complete eBooks as they continue their vast project to digitize the entirety of human knowledge.

In other cases, I simply have not yet reviewed the articles and posted them. If you are following this project, you see that I post updates nearly every day. Stay tuned.

My purpose in publishing Samizdat is to highlight excerpts from the great books, mining synchronicities from legends and myths. As I point out in the About page, the Deluge was an historical event for the ancient Sumerians.

I now need to update that page, incorporating the research that we have already completed on the Sumerian King List, setting up a future digression into the concept of the Great Year, which Berossos associated with traditions of a Conflagration and the Deluge.

If you wondered where we were going, I wrote this for you.

Updated 20 November 2015, 23:39 hrs.

nor the qadištu nor the nu-gig are to be reckoned as sacred prostitutes, it remains necessary to prove that there was no such institution as sacred prostitution in Mesopotamia in spite of its widespread reputation among scholars, to which I would like to return in the conclusion.

nor the qadištu nor the nu-gig are to be reckoned as sacred prostitutes, it remains necessary to prove that there was no such institution as sacred prostitution in Mesopotamia in spite of its widespread reputation among scholars, to which I would like to return in the conclusion.

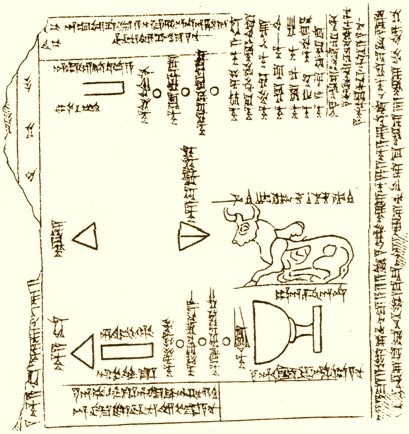

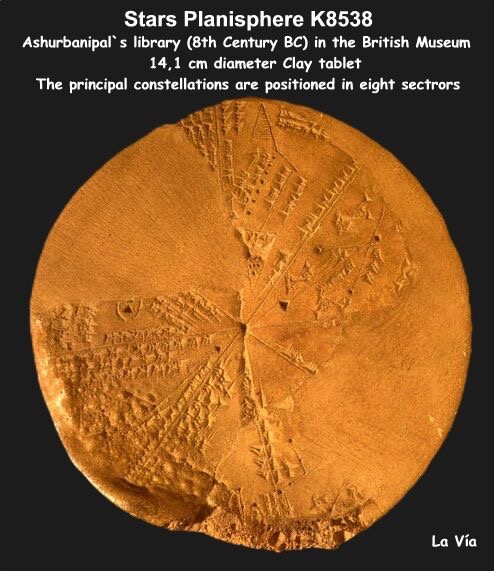

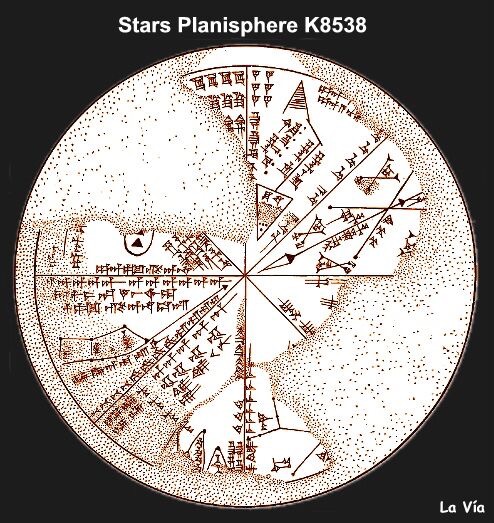

![Assyrian star planisphere found in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (Aššur-bāni-apli – reigned 668-627 BCE) at Nineveh. The function of this unique 13-cm diameter clay tablet, in which the principal constellations are positioned in eight sectors, is disputed. The texts and drawings appear to be astro-magical in nature. Kuyunjik Collection, British Museum, K 8538 [= CT 33, 10]. London. http://www.staff.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/babylon/babybibl.htm](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/babylonian-star-chart.jpg?w=500)

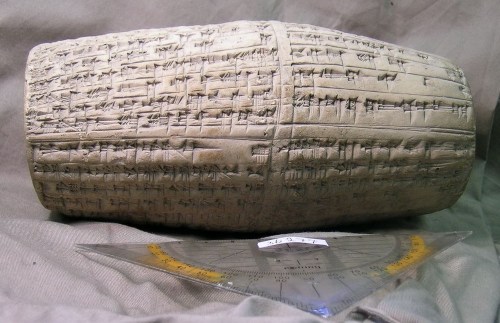

![In 1847 archaeologists discovered a prism of Sargon dated to the early 8th century BC reading: "At the beginning of my royal rule, I…the town of the Samarians I besieged, conquered (2 Lines destroyed) [for the god…] who let me achieve this my triumph… I led away as prisoners [27,290 inhabitants of it (and) equipped from among them (soldiers to man)] 50 chariots for my royal corps…. The town I rebuilt better than it was before and settled therein people from countries which I had conquered. I placed an officer of mine as governor over them and imposed upon them tribute as is customary for Assyrian citizens." (Nimrud Prism IV 25-41) https://theosophical.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg?w=500)

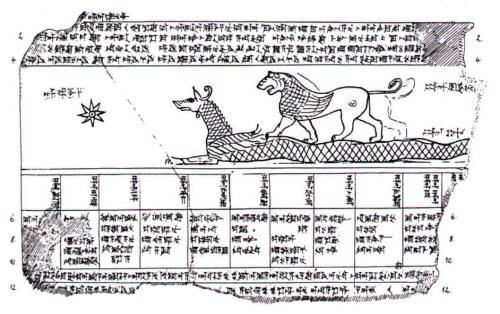

![http://doormann.tripod.com/asssky.htm Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff.](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/assyrian-star-map-from-nineveh.jpg?w=500)