Selz: Connects the Apkallu with the Fallen Angels

by Estéban Trujillo de Gutiérrez

“The correspondance between Enmeduranki, for a long time considered to be the Mesopotamian Enoch, with an apkallū named Utu-abzu, proved highly informative.

(See W.G. Lambert, “Enmeduranki and Related Matters,” JCS 21 (1967): pp. 126-38; idem, “New Fragment.”)

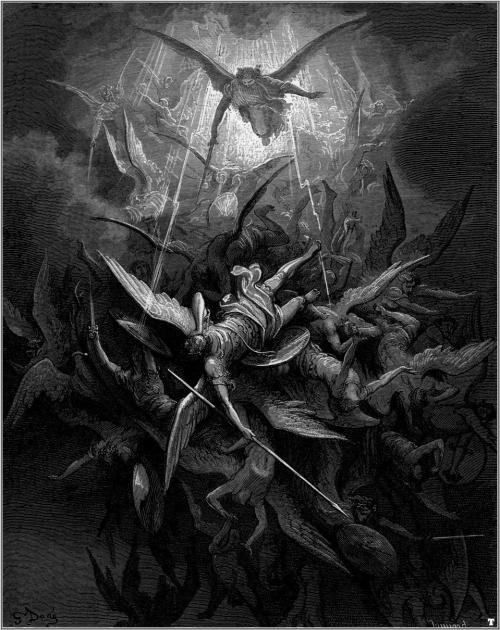

Paul Gustave Doré (1832-1883 CE), Michael Casts out all of the Fallen Angels, Illustration for Milton’s Paradise Lost, 1866.

This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art. The work of art itself is in the public domain for the following reason:

This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Doré

In 1974 Borger observed in an important article, that in tablet III of the omen series Bīt Mēseri (“House of Confinement”) a list of these apkallū is provided and that the apkallū Utu-abzu who is, as we have just seen, associated with the primeval ruler Enmeduranki is explicitly said to have “ascended to heaven.”

(“Beschwörung. U-anna, der die Pläne des Himmels und der Erde vollendet, U-anne-dugga, dem ein umfassender Verstand verliehen ist, Enmedugga, dem ein gutes Geschick beschieden ist, Enmegalamma, der in einem Hause geboren wurde, Enmebu-lugga, der auf einem Weidegrund aufwuchs, An-Enlilda, der Beschwörer der Stadt Eridu,” Utuabzu, der zum Himmel emporgestiegen ist, . . . ” (Borger, “Beschwörungsserie,” p. 192).

(“Summons. U -anna, completes the plans of the heavens and the earth, U-anne-dugga, accompanied by a comprehensive understanding, Enmedugga, who is granted good skill, Enmegalamma, who was born in a house, Enmebu-lugga, who grew up on a pasture, An-Enlilda, the Summoner of the city Eridu.”)

In Borger’s words we can therefore say: “The mythological conception of Enoch’s ascension to heaven derives . . . from Enmeduranki’s counselor, the seventh antediluvian sage, named Utuabzu!”

(Borger, “Incantation Series,” p. 232.)

Purādu-fish apkallū were antediluvian sages, the famous Seven Sages of Sumeria were purādu-fish.

The genotype is also attested in Berossus, as the form of the mentor of mankind, Oannes.

The iconographic evidence for these apkallū is manifold and best known from various Assyrian reliefs. We usually refer to them as genii. Bīt Mēseri, however, describes them as purādu-fishes, and this coincides with iconographic research undertaken by Wiggerman some twenty years ago in his study on Mesopotamian Protective Spirits.

(F.A.M. Wiggermann, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts (Cuneiform Monographs 1; Groningen: Styx, 1992).

The three types of apkallū are portrayed, with the human ummânū at far left, the Nisroch bird-apkallū type in the middle, and the antediluvian purādu-fish type at far right.

The human ummânū is attested in the Uruk List of Kings and Sages, while other references to bird-apkallū are legion, as documented in Wiggermann and other authorities.

The purādu-fish apkallū is principally attested in Berossus, though other authorities confirm them, as well.

The anthropomorphic qualities of the purādu-fish and the Nisroch apkallū remain unexplained, though the eagle is sacred to Enki / Ea.

Wiggerman could distinguish between basically three types of genii, attested in the Mesopotamian art: First, there is a human faced genius, second, a bird apkallū who occur only in “Assyrian” contexts, and third, a fish apkallū, the original Babylonian apkallū, as described by Berossos; according to the texts the last two groups of apkallū are coming in groups of seven.

The first type, the human faced genius must be kept apart because these genii are depicted wearing a horned crown which explicitly marks them as divine.

An ummânu, or sage of human descent. The ummânu raises his right hand in the iconic gesture of greeting, with what appear to be poppy bulbs in his left hand. Note the rosette design on his wristband, and the horned tiara headdress, indicative of divinity. Such human apkallū are invariably portrayed with wings, a further indicator of divinity or semi-divinity.

I cannot dwell here on the complicated issue of a possible intertextual relation between these apkallū and the “fallen angels” of the biblical tradition. Instead I will add some remarks concerning the following feature of the Enochic tradition, especially the Book of Giants.

1 Enoch 6:1-3 gives account of the siring of giants; men had multiplied and the watchers, the sons of heaven, saw their beautiful daughters and desired them.

Therefore, “they said to one another, ‘Come, let us choose for ourselves wives from the daughters of men, and let us beget children for ourselves.’

And Shemihazah, their chief, said to them, ‘I fear that you will not want to do this deed, and I alone shall be guilty of a great sin.’”

1 Enoch 7:1-2 describes that the women conceived from them and “bore to them great giants. And the giants begot Nephilim, and to the Nephilim were born . . . And they were growing in accordance with their greatness.”

Gebhard J. Selz, “Of Heroes and Sages–Considerations of the Early Mesopotamian Background of Some Enochic Traditions,” in Armin Lange, et al, The Dead Sea Scrolls in Context, v. 2, Brill, 2011, pp. 794-5.

[…] Selz: Connects the Apkallu with the Fallen Angels. […]

LikeLike