Selz: The Dream of Gudea

by Estéban Trujillo de Gutiérrez

“Whereas the giants sent Mahway to Enoch for an interpretation of their dreams, in earliest parallels from Mesopotamia the deities undertake this task:

(“Thereupon] all the giants [and monsters! grew afraid 15 and called Mahway to them and the giants pleaded with him and sent him to Enoch 16 [the noted scribe]” (Q II:). Translation taken from the Book of Giants edition of The Gnostic Society Library.)

Cuneiform cylinders of the Sumerian ruler Gudea. Dated to 2125 BCE, they recount the Building of Ningursu’s temple. Made by Gudea, ruler of Lagash, and excavated in 1877 during digs by Ernest de Sarzec beneath the Eninnu temple complex at Telloh (ancient Girsu), the complete name of the temple complex was “E-Ninnu-Imdugud-babbara,” meaning “House Ninnu, the Flashing Thunderbird,” a reference to a thunderbird in the second dream that compelled Gudea to build the temple.

Now in the permanent collection of the Louvre Museum, the pair are the largest cuneiform cylinders ever recovered, and they contain the longest known Sumerian text. Anomalous shards recovered on the same site indicate that a third cylinder did not survive the ravages of time. Labelled Cylinders A and B, the cuneiform was intended to be read with the cylinders in a horizontal position with a perforation in the middle for mounting.

The text has been translated by Jeremy Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson and G. Zólyomi, available from The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford, 1998.

http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section2/tr217.htm

Accession numbers MNB 1511 and MNB 1512.

Photo by Ramessos.

I, the copyright holder of this work, release this work into the public domain. This applies worldwide.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gudea_cylinders

The Sumerian ruler Gudea had difficulties to understand the precise meaning of his dream and addresses the goddess Nanshe, firstly describing his visions:

“(4:8) Nanshe, mighty queen, lustration priestess, protecting genius, cherished goddess of mine, . . . You are the interpreter of dreams among the gods, you are the queen of all the lands, O mother, my matter today is a dream.

There was someone in my dream, enormous as the skies, enormous as the earth was he.

That one was a god as regards his head, he was the Thunderbird as regards his wings, and a floodstorm as regards his lower body. There was a lion lying on both his left and right side . . . (but) I did not understand what (exactly) he intended. Daylight rose for me on the horizon.

(4:23) (Then) there was a woman—whoever she might have been—she (the goddess Nissaba[k]) held in her hand a stylus of shining metal, on her knees there was a tablet (with) stars of heaven, and she was consulting it.

(5:2) Furthermore, there was a warrior who bent (his) arm holding a lapis lazuli plate on which he was setting the ground-plan of a house. He set before me a brand-new basket, a brand-new brick-mould was adjusted and he let the auspicious brick be in the mould for me.”

(The translation from Cylinder A follows D.O. Edzard, ed., Gudea and his Dynasty (RIME 3:1, Toronto: University of Toronto Press,1997), pp. 71-2. Emphases are mine, G.J.S.).

Using much the same words the goddess explains the dream:

“(5:12) My shepherd, I will interpret your dream for you from beginning to end: The person who you said was as enormous as the skies, enormous as the earth, who was a god as regards his head, who, as you said, was the Thunderbird as regards his wings, and who, as you said, was a floodstorm as regards his lower parts, at whose left and right a lion was lying—he was in fact my brother Ningirsu-k; he talked to you about the building of his shrine Eninnu.

The daylight that had risen for you on the horizon—that was your (personal) god Ningishzida-k: like daylight he will be able to rise for you from there.

The young woman coming forward, who did something with sheaves, who was holding a stylus of shining metal, had on her knees a tablet (with) stars, which she was consulting was in fact my sister Nissaba-k—she announced to you the bright star (auguring) the building of the House.

Furthermore, as for the warrior who bent his arm holding a lapis lazuli plate—he was Ninduba: he was engraving thereon in all details the ground-plan of the House.”

Certainly, the setting of this dream is very different from those of the Enoch tradition. We note, however, that the dreams in the Book of Giants also show a clear connection with the scribal art, especially the “Tablets of Heavens,” to the dreams as a message of God and also to the flood.

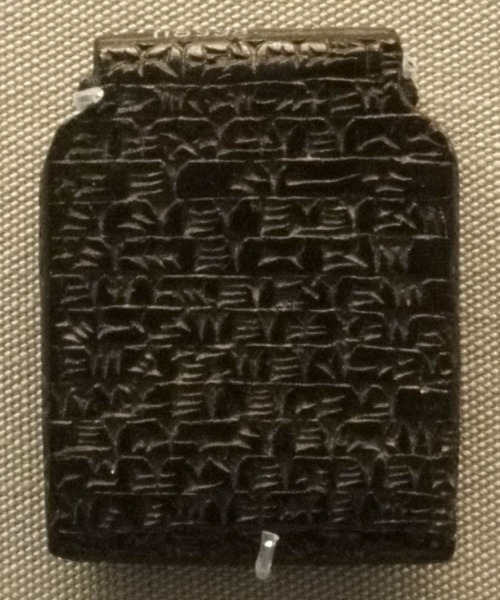

Black stone amulet against plague.

A quotation from the Akkadian Epic of Erra.

BM 118998, British Museum, Room 55.

Registration: 1928,0116.1.

Photo by Fae.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

The latter motif as found in the Book of Giants shows a clear connection to the story of the Erra Epic, where to Marduk’s horror, the deity of pestilence and destruction, Erra, decides to annihilate mankind and its foremost sanctuaries.

The reason for the annihilation of the world and the expression of a certain degree of hope looks very similar indeed. It is important to note that this text from the eight century BCE had a considerable audience as can be deduced from the over 35 tablets unearthed so far.

In many respects, the wording of the text and its attitude ask for elaborate comparison with the Jewish apocalyptical tradition, but this would be another article.”

(For an overview of Mesopotamian “apocalyptic motifs” see C. Wilcke, “Weltuntergang als Anfang: Theologische, anthropologische, politisch-historische und ästhetische Ebenen der Interpretation der Sintflutgeschichte im babylonischen Atram-hasīs-Epos,” in Weltende: Beiträge zur Kultur-und Religionswissenschaft (ed. A. Jones; Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1999), pp. 63-112.)

Gebhard J. Selz, “Of Heroes and Sages–Considerations of the Early Mesopotamian Background of Some Enochic Traditions,” in Armin Lange, et al, The Dead Sea Scrolls in Context, v. 2, Brill, 2011, pp. 797-9.

[…] Selz: The Dream of Gudea. […]

LikeLike