“Jupiter, the largest of the planets, was identified with Merodach, head of the Babylonian pantheon. We find him exercising control over the other stars in the creation story under the name Nibir.

Ishtar was identified with Venus, Saturn with Ninib, Mars with Nergal, Mercury with Nabu. It is more than strange that gods with certain attributes should have become attached to certain planets in more countries than one, and this illustrates the deep and lasting influence which Semitic religious thought exercised over the Hellenic and Roman theological systems.

The connexion is too obvious and too exact not to be the result of close association. There are, indeed, hundreds of proofs to support such a theory. Who can suppose, for example, that Aphrodite is any other than Ishtar?

The Romans identified their goddess Diana with the patroness of Ephesus. There are, indeed, traces of direct relations of the Greek goddess with the moon, and she was also, like Ishtar, connected with the lower world and the sea.

The Greeks had numerous and flourishing colonies in Asia Minor in remote times, and these probably assisted in the dissemination of Asiatic and especially Babylonian lore.

The sun was regarded as the shepherd of the stars, and Nergal, the god of destruction and the underworld, as the “chief sheep,” probably because the ruddy nature of his light rendered him a most conspicuous object.

Anu is the Pole Star of the ecliptic, Bel the Pole Star of the equator, while Ea, in the southern heavens, was identified with a star in the constellation Argo.

Fixed stars were probably selected for them because of their permanent and elemental nature. The sun they represented as riding in a chariot drawn by horses, and we frequently notice that the figure representing the luminary on Greek vases and other remains wears the Phrygian cap, a typically Asiatic and non-Hellenic headdress, thus assisting proof that the idea of the sun as a charioteer possibly originated in Babylonia.

Lunar worship, or at least computation of time by the phases of the moon, frequently precedes the solar cult, and we find traces in Babylonian religion of the former high rank of the moon-god. The moon, for example, is not one of the flock of sheep under guidance of the sun. The very fact that the calendar was regulated by her movements was sufficient to prevent this.

Like the Red Indians and other primitive folk, the Babylonians possessed agricultural titles for each month, but these periods were also under the direct patronage of some god or gods.

Thus the first month, Nizan, is sacred to Anu and Bel; and the second, Iyar, to Ea. Siwan is devoted to Sin, and as we approach the summer season the solar gods are apportioned to various months.

The sixth month is sacred to Ishtar, and the seventh to Shamash, great god of the sun. Merodach rules over the eighth, and Nergal over the ninth month.

The tenth, curiously enough, is sacred to a variant of Nabu, to Anu, and to Ishtar. The eleventh month, very suitably, to Ramman, the god of storms, and the last month, Adar, falling within the rainy season, is presided over by the seven evil spirits.

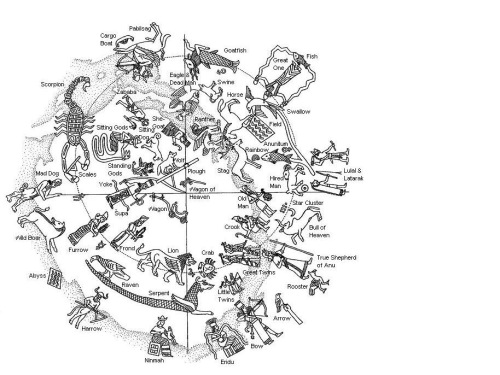

![Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff. http://doormann.tripod.com/asssky.htm](https://ma91c1an.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/assyrian-star-map-from-nineveh.jpg?w=500)

Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff.

http://doormann.tripod.com/asssky.htm

None of the goddesses received stellar honours. The names of the months were probably quite popular in origin.

Thus we find that

- the first month was known as the ‘month of the Sanctuary,’

- the third as the ‘period of brick-making,’

- the fifth as the ‘fiery month,’

- the sixth as the ‘month of the mission of Ishtar,’ referring to her descent into the realms of Allatu.

- The fourth month was designated ‘scattering seed,’

- the eighth that of the opening of dams,

- and the ninth was entitled ‘copious fertility,’

- while the eleventh was known as ‘destructive rain.’

We find in this early star-worship of the ancient Babylonians the common origin of religion and science. Just as magic partakes in some measure of the nature of real science (for some authorities hold that it is pseudo-scientific in origin) so does religion, or perhaps more correctly speaking, early science is very closely identified with religion.

The Zodiac of Dendera (or “Dendara”), a stone diagram from an Egyptian temple dated to the mid-1st century BCE, depicts the twelve signs of the zodiac and the 36 Egyptian decans, and numerous other constellations and astronomical phenomena.

The Hellenistic-era portrayal of the zodiac is dated to between June 15th and August 15th, 50 BCE based on astronomical data in the diagram. The positions of planets in specific signs of the zodiac and eclipses that took place on March 7th, 51 BCE and September 25, 52 BCE are depicted.

The Dendera Egyptian temple complex dates back to the 4th century BCE, during the rule of the last native Egyptian pharaoh Nectanebo II. It was renovated by later Hellenistic and Roman rulers.

http://horoscopicastrologyblog.com/2007/05/24/the-zodiac-of-dendera/

Thus we may believe that the religious interest in their early astronomy spurred the ancient star-gazers of Babylonia to acquire more knowledge concerning the motions of those stars and planets which they believed to be deities.

We find the gods so closely connected with ancient Chaldean astronomy as to be absolutely identified with it in every way. A number was assigned to each of the chief gods, which would seem to show that they were connected in some way with mathematical science.

Thus Ishtar’s number is fifteen; that of Sin, her father, is exactly double that. Anu takes sixty, and Bel and Ea represent fifty and forty. Ramman is identified with ten.

It would be idle in this place to attempt further to outline astrological science in Babylonia, concerning which our knowledge is vague and scanty. Much remains to be done in the way of research before anything more definite can be written about it, and many years may pass before the workers in this sphere are rewarded by the discovery of texts bearing on Chaldean star-lore.”

Lewis Spence, Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria, 1917, pp. 235-7.

![Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff. http://doormann.tripod.com/asssky.htm](https://ma91c1an.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/assyrian-star-map-from-nineveh.jpg?w=500)

![Assyrian star planisphere found in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (Aššur-bāni-apli – reigned 668-627 BCE) at Nineveh. The function of this unique 13-cm diameter clay tablet, in which the principal constellations are positioned in eight sectors, is disputed. The texts and drawings appear to be astro-magical in nature. Kuyunjik Collection, British Museum, K 8538 [= CT 33, 10]. London. http://www.staff.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/babylon/babybibl.htm](https://ma91c1an.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/babylonian-star-chart.jpg?w=500)