“Parpola discusses the role of these experts in relation to the king. Did the experts form a clique that was in the position to manipulate the king according to its own agenda? Parpola denies this possibility; on the one hand the “inner circle” was not permanently present at the court; on the other hand there was clearly rivalry between the scholars. In addition, the advisory role of the scholars was overwhelmingly passive and “academic.”

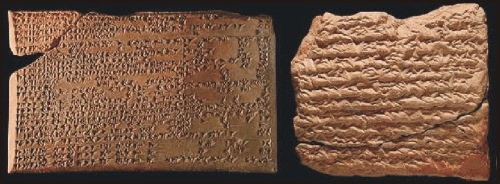

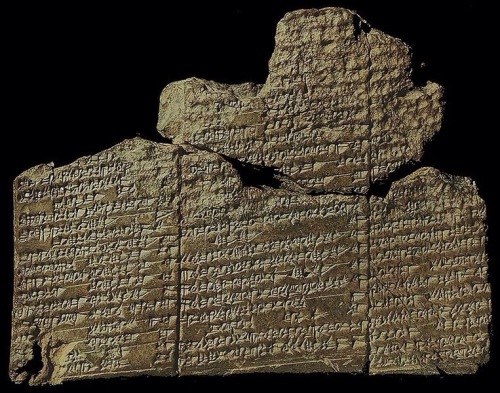

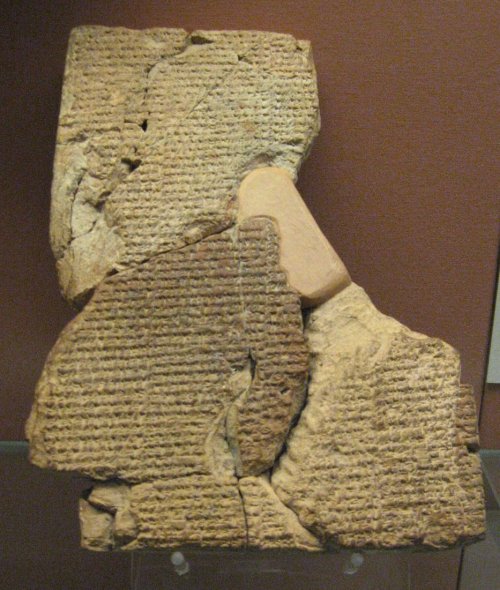

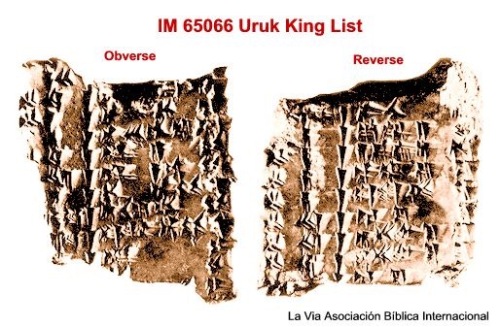

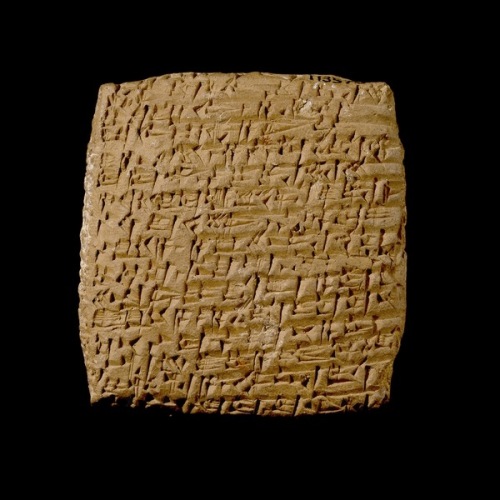

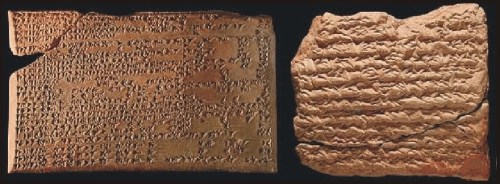

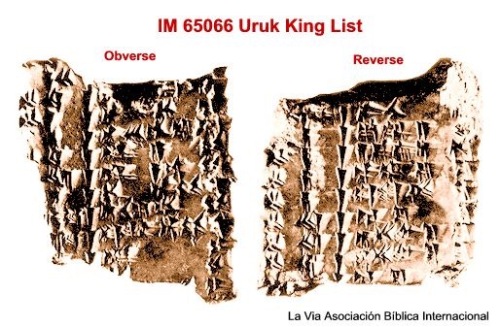

The cuneiform tablet (IM 65066) is in the Bagdad Museum.

A.K. Grayson, from the Reallexikon der Assyriologie, s.v. “Königslisten und Chroniken”.

A.K. Grayson, ‘Assyrian and Babylonian King Lists,’ in: Lišan mithurti. (Festschrift Von Soden) (Kevelaer : Neukirchen-Vluyn : Butzon & Bercker; 1969) Plate III.

http://www.livius.org/source-content/uruk-king-list/

Nevertheless, the importance of the scholars for the king must not be underestimated. They represented a wisdom going back to the seven apkallus from before the flood, and this wisdom was indispensable for the king. The experts provided the royal family with medical care (physicians and exorcists), protection against demons and angry gods (exorcists and chanters), and they provided the king with insight into the future (haruspices and astrologers).

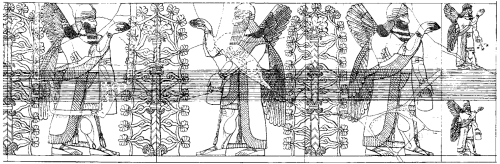

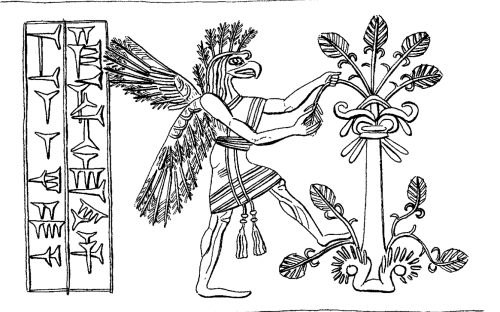

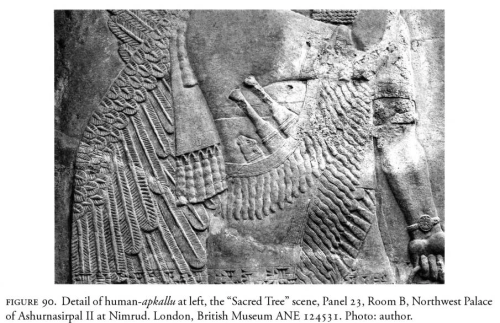

This appears to be an ummanu without wings, blessing the sacred tree with his right hand raised in the greeting gesture and his lowered left hand holding drooping poppy bulbs. This depiction of an apkallu wears a dual-horned tiara indicative of divinity or semi-divinity, but lacks all other indicators like wings. As the typical mullilu cone and banduddu bucket are absent, this could depict a king saluting the tree. Still, the figure wears a horned tiara, which is reserved for apkallu, and not worn by kings.

The horned tiara is atypical with a distinctive fleur de lis at the apex. Indeed this frieze is remarkably detailed, with three separate bands visible on the rosette bracelets, and individual strands visible on the tasseled garment.

The sacred tree is sparse and stark in comparison to other renditions, though it appears to be blossoming from a fleur de lis base.

(Génie tenant une fleur de pavot – Genie carrying a poppy flower.)

Bas-relief, 144 x 17cm.

Louvre, AO 19869

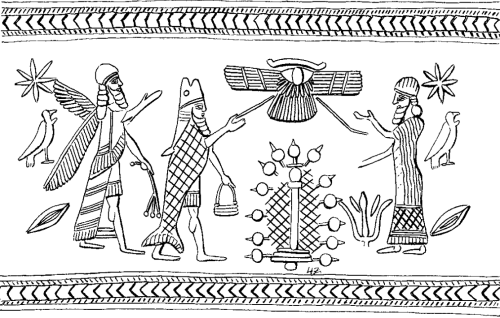

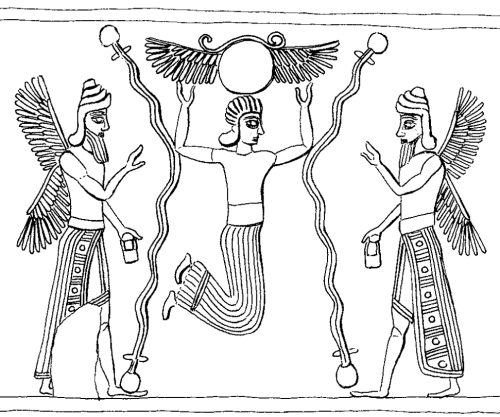

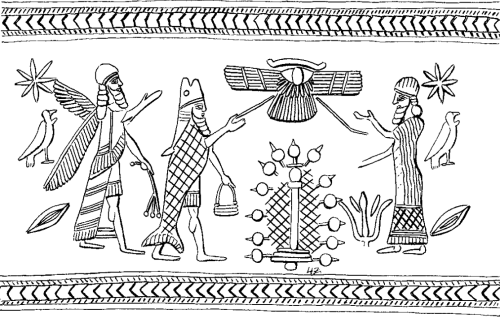

Both on Assyrian reliefs and cylinder seals depictions of the apkallus together with a date palm, and in some instances the king, are common. The date palm is here a holy tree, the Tree of Life. It symbolizes the benefits the gods and kings were expected to supply for the people.

(Click to zoom in)

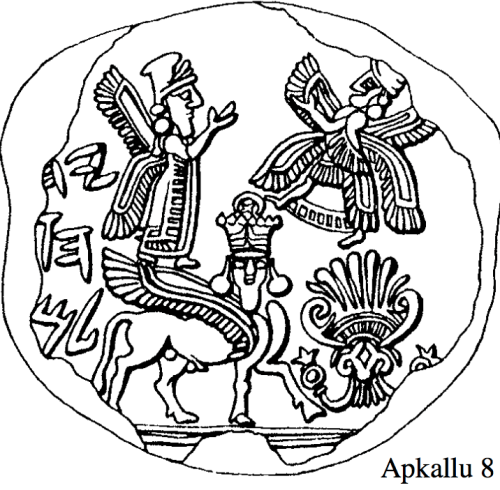

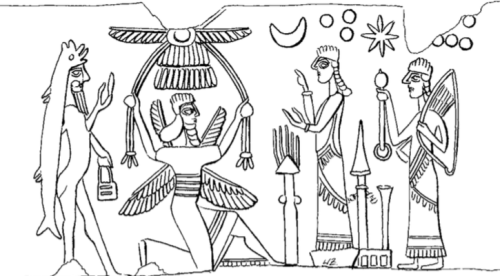

On the imprint from this chalcedony cylinder seal dated to the 9th Century BCE, an umu-apkallu, an ummanu, winged with mullilu and banduddu bucket, blesses (or pollinates) the sacred tree with an undefined female figure.

Note that this more or less symmetrical rendition of the sacred tree is mounted on a pedestal with bulbs that resemble cones.

Cylinder seal and imprint: Cult of the sacred tree. Chalcedony,

H: 3,2 cm

Louvre: AO 22348

(“This palm in art then is not the symbol of a god or the whole pantheon of gods, but is a symbol of the benefits which gods and kings were expected to supply.” W.G. Lambert, “The Background of the Neo-Assyrian Sacred Tree,” in S. Parpola and R.M. Whiting, eds., Sex and Gender in the Ancient Near East, XLVIIe Recontre Assyriologique Internationale, Helsinki, 2002, pp. 321-6.)

The role of the apkallus is to pollinate the tree. Through this guest (sic), fertility, vitality, and power were transferred to the tree; in the scenes where the king is present, he is a receiver of these benefits from apkallus.

(Cf. Kolbe, Die Reliefprogramme, 21, 29, pp. 83-8).

Parpola returns to this mythological representation of the role of the king in his new edition of the letters. The Assyrian kings had the position of the god’s representative on earth. This position was above all symbolized through the Tree of Life.

(Parpola, Letters from Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars, XIII-XXXV.)

Three superposed lotus flowers forming a “Sacred tree.” Ivory (open-work, fragment)

Right: Lotus flower with 5 petals.

11.3 x 3 cm, Louvre AO 11481;

Left: Ivory plaque with top and bottom border from Arslan Tash, ancient Hadatu, Northern Syria.

7.6 x 2.1 cm, Louvre AO 11482.

I believe that the sacred tree fragment on the left is upside down. The blossoms should be oriented upwards.

The tree represented the divine world order maintained by the king. At the same time the symbolism of the tree was projected upon the king as the perfect image of the god. A king who could not conform to this role would automatically disrupt the cosmic harmony.

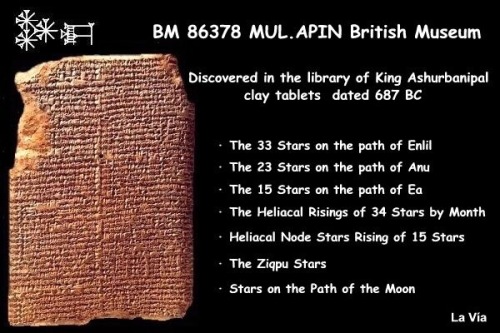

To execute this duty the king needed experts who could interpret the signs of the god. Therefore he needed the advisory circle of scholars: the tupšarru, “astrologer, scribe;” bārû, “haruspex / diviner;” āšipu, “exorcist / magician;” asû, “physician;” and kalû, “lamentation chanter.”

A memorandum from the reign of Ashurbanipal names 45 scholars from these professions. The scholars were mostly native, but could also include foreigners, such as Syrian, Anatolian, and Egyptian.

(Parpola, Letters from Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars, XIV.)

Click to zoom in.

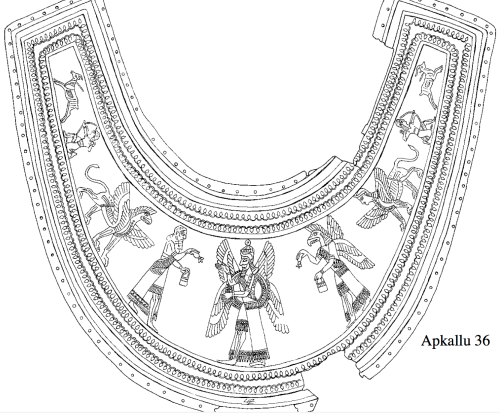

This reproduction of the bas reliefs in Room I of the Northwestern Palace of King Ashurnasirpal at Nimrud is remarkable for the sheer number of apkallus portrayed interacting with endless renditions of the sacred tree.

All apkallu are winged, even the beardless specimens in I-16. All others are either bearded males, or griffin-headed bird apkallus.

Samuel M. Paley and R.P. Sobolewski, The Reconstruction of the Relief Representations and Their Positions in the Northwest Palace at Kalhu (Nimrud) II. (The Principal Entrances and Courtyards). Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1992.

From Mehmet-Ali Atac, The Mythology of Kingship in Neo-Assyrian Art, Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 100.

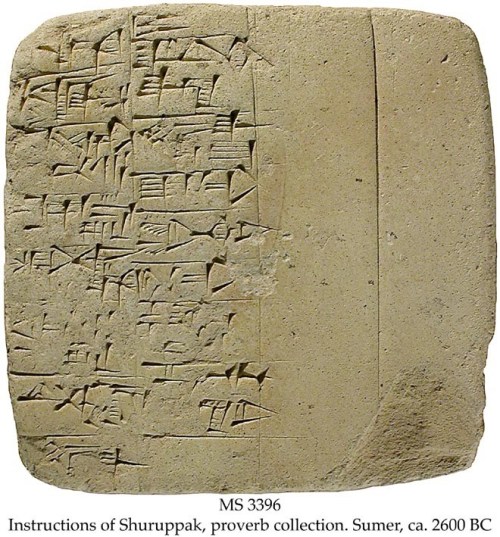

The Catalogue of Texts and Authors shows that the actual scholars at the royal court stood in a line of transmission; they performed a profession, the wisdom of which went back to famous ummanus of the past, and ultimately to the antediluvian apkallus.

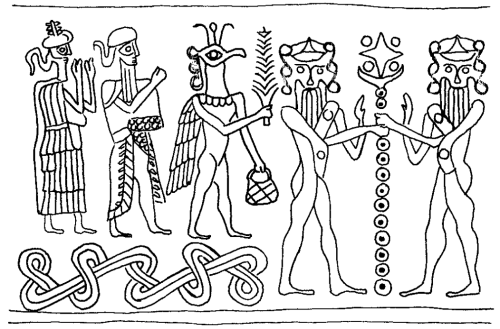

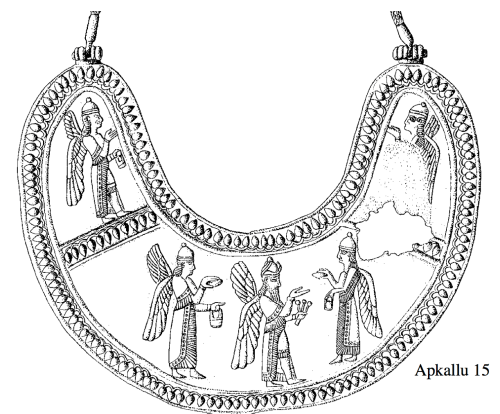

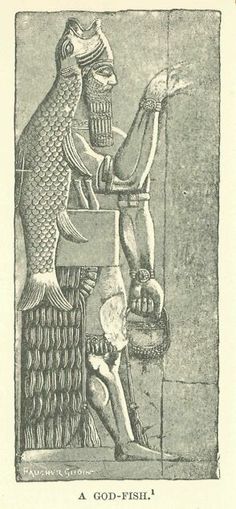

These apkallus were, as we have seen in the rituals, imagined in three shapes. The fish-garb symbolized the connection with apsû, the ocean of wisdom; the head and wings of the eagle symbolized their connection to heaven.

The genies symbolizing the human apkallus often have crowned horns, indicating divine status. Parpola thinks that this symbolized their transformation from humans to saints after their death. (Ibid., XX). “

Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011, pp. 143-4.