Gane: Review of the Literature on Monsters, Demons and gods

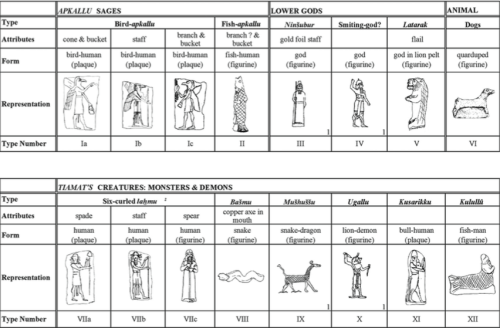

“When a monster is associated with an anthropomorphic deity, it operates in the same field of action or part of nature as that of the deity.

Whereas the deity functions in the entire domain of his or her rule, the monster’s activity is limited to only part of the god’s realm. Thus, a monster that is associated with a deity as its attribute creature represents part of the divine nature or a particular aspect of the divine function of the god.

Wiggermann observes that after a developmental period, during which Mesopotamian gods and monsters evolved, they eventually settled into “complementary” opposition in which “the gods represent the lawfully ordered cosmos, monsters represent what threatens it, the unpredictable.”

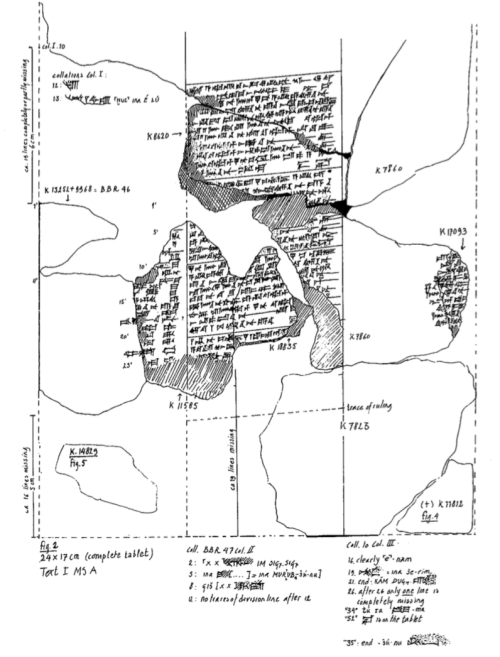

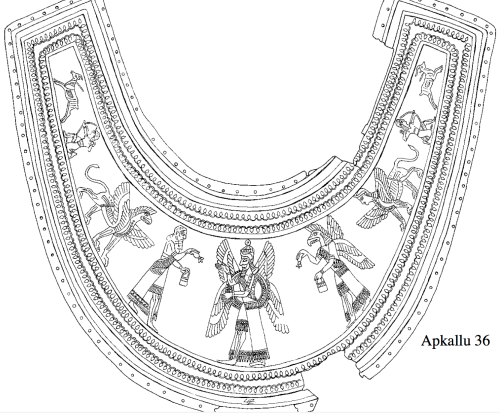

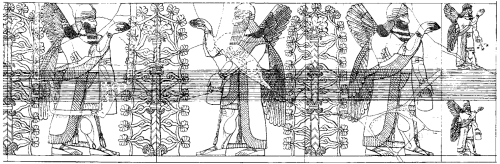

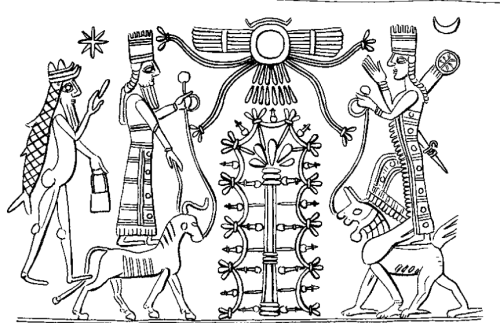

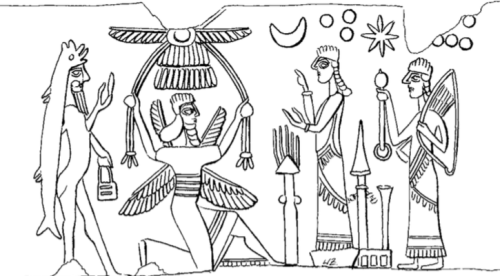

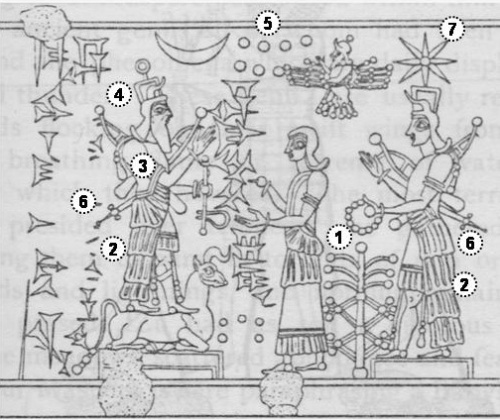

Detail from a drawing of a bronze plaque held in the Louvre.

Puradu-fish apkallu minister to an ill patient in bed. The lamp of Nusku is depicted at far left, and ugallu attack with upraised fists in concert with Lulal, identified by Wiggerman as “a minor apotropaic god.”

I believe that this plaque portrays an exorcism.

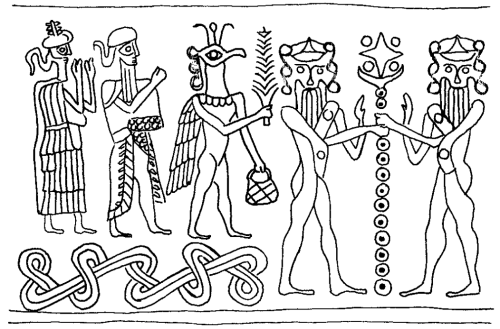

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a bronze plaque of which an engraving was published by Clermont-Ganneau.

The original, which belonged to M. Péretié, was in the collection of M. de Clercq before it was acquired by the Louvre.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17323/17323-h/17323-h.htm#linkBimage-0039%5B/caption%5D

Wiggermann’s 2007 article, “Some Demons of Time and Their Functions in Mesopotamian Iconography,” in Die Welt der Götterbilder, updates research on a number of the hybrid creatures under discussion in the present study.

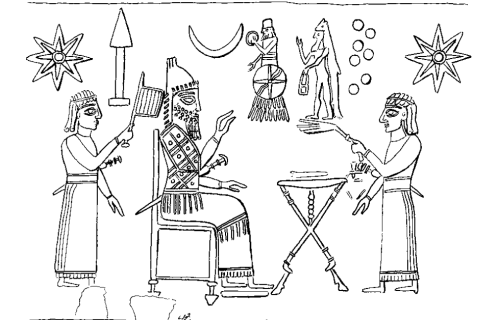

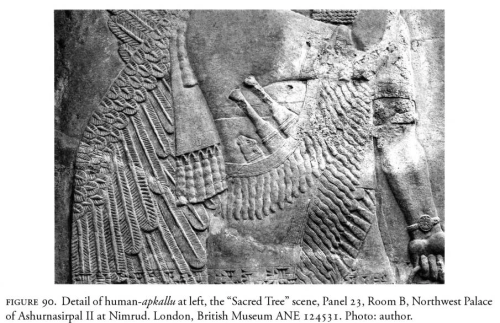

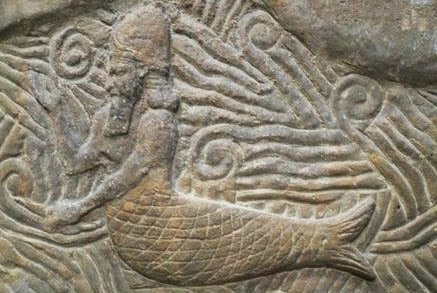

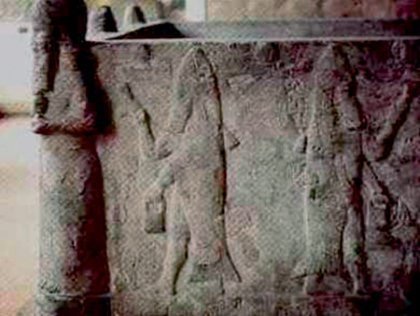

[caption width="432" id="attachment_2864" align="aligncenter"] This is the actual bronze frieze from which the illustration above is extracted, held in the collection of the Louvre as AO 22205.

This is the actual bronze frieze from which the illustration above is extracted, held in the collection of the Louvre as AO 22205.

(Frans A. M. Wiggermann, “Some Demons of Time and Their Functions in Mesopotamian Iconography,” in Die Welt der Götterbilder (ed. Hermann Spieckermann and Brigitte Groneberg; Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 376; Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2007).

The 1992 illustrated dictionary written by Jeremy A. Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, has provided an initial launching point for dealing with the maze of interrelated deities, demons, and composite creatures of ancient Mesopotamia.

(Jeremy A. Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia (illustrated by Tessa Richards); Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992).

While the work is far from exhaustive and does not provide references for its sources, it has proven to be a valuable guide through the daunting complexities of the topic.

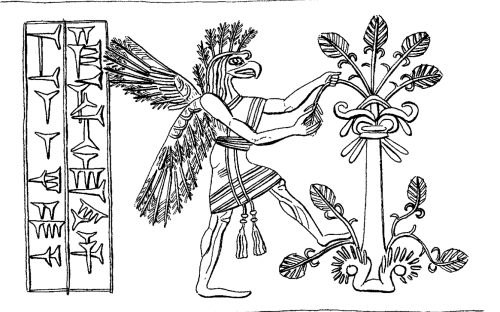

This lion-headed eagle was called Anzu in Akkadian and Imdugud in Sumerian. It was symbolic of the god Ningursu.

In the Myth of Anzu, the Anzu steals the me, the Tablet of Destinies, from the god Ea, when he disrobed to bathe.

The Tablet of Destinies was a cuneiform tablet upon which the fates of all creatures were written, granting its holder supreme power.

It was Ningursu who defeated the Anzu and recovered the me. Other versions of the myth claim that Anzu stole the me from Enlil, with Ninutra recovering it.

Source: Stephanie Dalley, Myths From Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford University Press, 1991.

http://www.piney.com/Babmythanzu.html

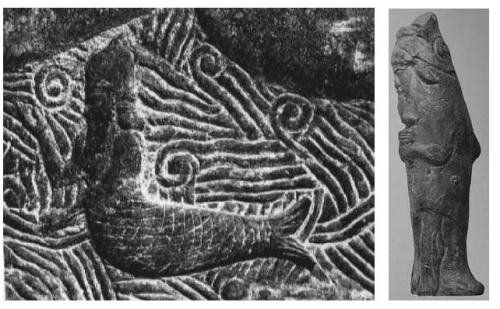

This panel was excavated from the ruins at the base of the Temple of Goddess Ninhursag at Tell-Al-Ubaid in Southern Mesopotamia (Iraq).

Dated to the Early Dynastic Period, circa 2500 BCE, this artifact is currently held by The British Museum.

Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, this file is licensed under the Creative Common Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frieze_of_Imdugud_(Anzu)_grasping_a_pair_of_deer,_from_Tell_Al-Ubaid..JPG%5B/caption%5D

A number of works by Green are formative in the study of composite creatures. He has written numerous articles, among which the most significant are his 1984 article, “Beneficent Spirits and Malevolent Demons: The Iconography of Good and Evil in Ancient Assyria and Babylonia,” and his 1997 RlA article on “Mischwesen. B. Archäologie.”

(Anthony Green, “Beneficent Spirits and Malevolent Demons: The Iconography of Good and Evil in Ancient Assyria and Babylonia,” Visible Religion 3 (1984): pp. 80-105.

Anthony Green, “Mischwesen. B. Archäologie,” Reallexikon der Assyeriologie (RlA) 8: pp. 246-264.)

In 2003, Paul-Alain Beaulieu published The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. This work provides a systematic, period-specific treatment of Neo-Babylonian religion at the ancient site of Uruk.

(Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period (CM 23; Leiden: Brill, 2003. Note: this book in its entirety is available for free download from archive.org in multiple formats including .pdf. Say thank you to the publishers, Brill.)

One of the most important current resources is Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East, edited by Jürg Eggler, which is still under development, but available in electronic pre-publication form.

(Jürg Eggler, ed., Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East, Electronic Pre-Publication ed., n.p. [cited 11 July 2012 and verified 21 October, 2015]. Online: http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/index.php.)

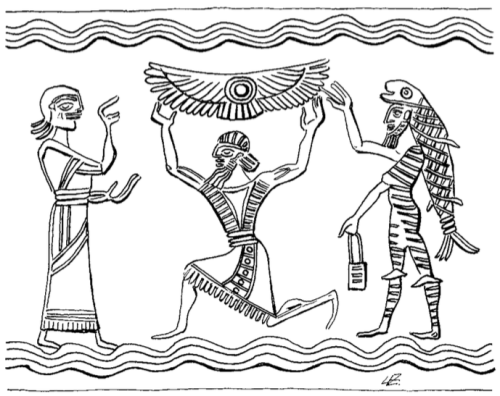

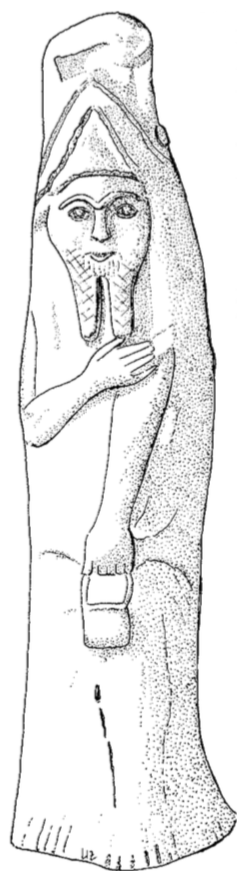

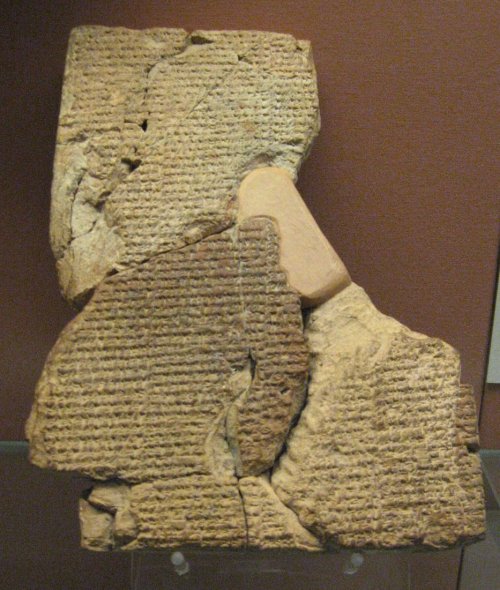

[caption width="600" id="attachment_2344" align="aligncenter"] Amulet with a figure of Lamashtu

Amulet with a figure of Lamashtu

From Mesopotamia, around 800 BC

A demonic divinity who preys on mothers and children

This is a protective image of Lamashtu, a fearsome female divinity of the underworld, intended to keep evil at bay. Although she is usually described in modern works as a demon, the writing of her name in cuneiform suggests that in Babylonia and Assyria she was regarded as a kind of goddess. Unlike the majority of demons, who acted only on the commands of the gods, Lamashtu practised evil apparently for its own sake and on her own initiative. There is a cuneiform incantation on the reverse to frighten her away.

Lamashtu’s principal victims were unborn and new-born babies. Slipping into the house of a pregnant woman, she tries to touch the woman’s stomach seven times to kill the unborn baby, or she kidnaps the child. Magical measures against Lamashtu included wearing a bronze head of Pazuzu. Some of these plaques show a bedridden man rather than a pregnant woman, so they seem to relate to Lamashtu as a bringer of disease.

Lamashtu is described in texts as having the head of a lion, the teeth of a donkey, naked breasts, a hairy body, stained hands, long fingers and finger nails, and the talons of a bird. Plaques also show her suckling a piglet and a whelp while she holds snakes in her hands. She stands on her sacred animal, the donkey, which is sometimes shown in a boat, riding through the underworld.

H.W.F. Saggs, Babylonians (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

J. Black and A. Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia (Austin, University of Texas Press, 1992)

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/a/amulet_with_figure_of_lamashtu.aspx

The 2004 catalogue accompanying the exhibition titled “Dragons, Monsters and Fabulous Beasts in the Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem” and compiled by Joan Goodnick Westenholz illustrates the formation and function of hybrid creatures in the ancient Near East and the classical world.

The catalogue, following the format of the exhibition, is divided into four main areas: “creatures of the sea, creatures of the earth, creatures of the air, and the battles of the gods and mortals against the monsters.”

(Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Dragons, Monsters and Fabulous Beasts, Rubin Mass, 2007, p. 9.)

The treatment of selected composite beings is detailed, but limited to the examples specific to the exhibit.

A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East, edited by Billie Jean Collins (2002), focuses on animals found in Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran, and Syro-Palestine, with particular attention to the native fauna; animals in art, literature, and religion; and the cultural use of animals.

(Billie Jean Collins, ed., A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East (Handbook of Oriental Studies 64; Leiden: Brill, 2002). Note: Chapter 5 by Margaret Cool Root, “Animals in the Art of Ancient Iran,” is available for download from archive.org.)

The volume is more a historical narrative of human relations with animals than a history of animals in the ancient world. As such, it provides insights into rationales behind selection of certain animals to represent particular characteristics of divine or sub-divine beings.

Collins builds on the work of E. Douglas Van Buren, whose formative study, The Fauna of Ancient Mesopotamia as Represented in Art (1939), focuses on forty-eight animal species, but without discussing their significance.”

(E. Douglas Van Buren, The Fauna of Ancient Mesopotamia as Represented in Art (AnOr 18; Rome: Institutum Biblicum, 1939).

Constance Ellen Gane, Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, Doctoral Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 2012, pp. 3-4.