Selz: Plant of Birth or Plant of Life in the Etana Legend?

“The story of Etana, one of the oldest tales in a Semitic language, was, as I have argued elsewhere, modeled after the then extant Sumerian tales of the Gilgamesh Epic.

Gilgamesh’s search for “the plant of life,” the ú-nam-ti-la (šammu ša balāti) was, however, replaced by Etana’s search for the plant of birth-giving (šammu ša alādi). The entire story runs as follows:

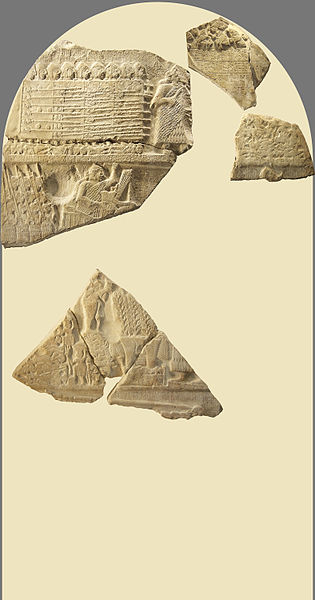

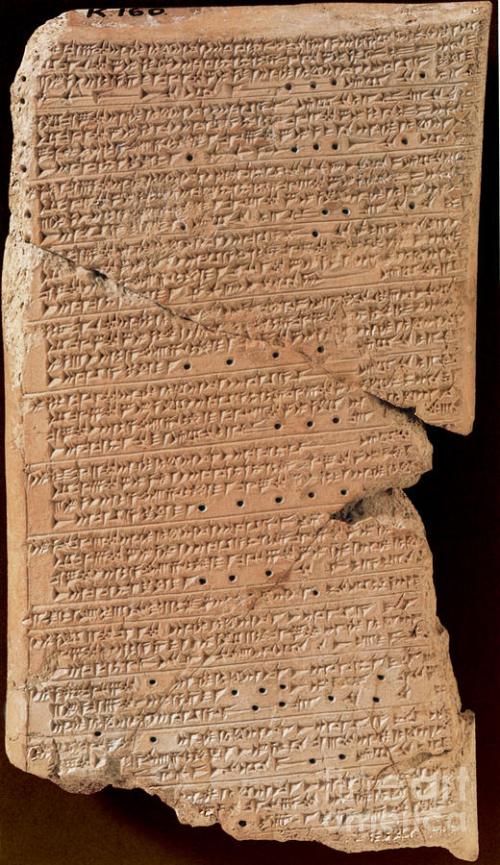

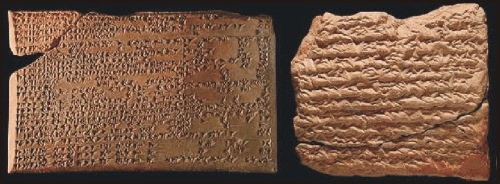

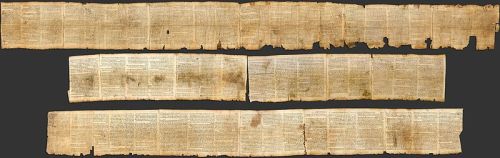

British Museum K. 19530, Library of Ashurbanipal (reigned 669-631 BCE), excavated from Kouyunjik by Austen Henry Layard. Neo-Assyrian 7th Century BCE, Nineveh.

This cuneiform tablet details the legend of Etana, a mythological king of Kish.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=287204&partId=1&searchText=WCT28297&page=1

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/c/cuneiform_the_legend_of_etana.aspx

This image is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

The gods build the first city Kish, but kingship is still in heaven. A ruler is wanted (and found). Due to an illness, Etana’s wife is unable to conceive. The plant of birth is wanted.

In the ensuing episode eagle and snake swore an oath of friendship. Suddenly the eagle plans to eat up the snake’s children; a baby eagle, with the name of Atrahasīs opposes this plan, but eagle executes it.

Now, the weeping snake seeks justice from the sun-god. With the god’s help the eagle is trapped in a burrow, and now the eagle turns to the sun-god for help. He receives the answer that, because of the taboo-violation he cannot help, but will send someone else.

Etana prays daily for the plant of birth and in a dream the sun-god tells Etana to approach the eagle. In order to get the eagle’s support Etana helps him out of his trap.

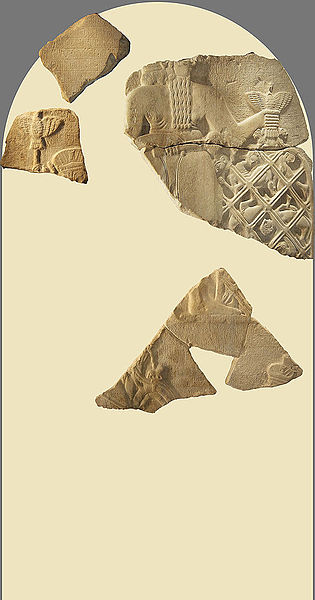

BM 89767, Limestone cylinder seal illustrating the myth of Etana, shepherd and legendary king of Kish, who was translated to heaven by an eagle to obtain the plant of life.

This seal portrays Etana’s ascent, witnessed by a shepherd, a dog, goats and sheep. Dated 2250 BCE, this seal was excavated by Hormuzd Rassam, and came from an old, previously unregistered collection acquired before 1884.

Dominique Collon, Catalogue of the Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum: Cylinder Seals II: Akkadian, Post-Akkadian, Ur III Periods, II, London, British Museum Press, 1982.

R.M. Boehner, Die Entwicklung der Glyptic wahrend der Akkad-Zeit, 4, Berlin, 1965.

Alfred Jeremias, Das Alte Testament im Lichte des Alten Orients: Handbuch zur biblisch-orientalischen Altertumskunde, Leipzig, JC Hinrichs, 1906.

Also AN128085001, 1983, 0101.299.

This image is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?partid=1&assetid=128085001&objectid=368707

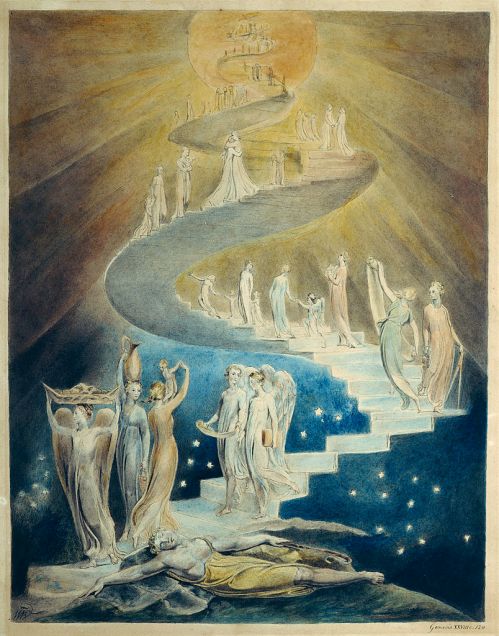

Now the eagle, carrying Etana on his back, ascends to the heavens. On the uppermost level of the heavens Etana becomes afraid and the eagle takes him back to the earth.

The end of the story is missing, but that Etana finally got hold of the plant of birth is very likely, since other sources mention his son.

To summarize: I have tried to show that some features of the Enoch tradition are a re-writing of very ancient concepts. I do not claim that they all can be explained assuming dependencies, as earlier scholarship has done.

I do not intend to idolize “origins,” but what might eventually come out of such a research—if the topics mentioned here are thoroughly worked out and elaborated in detail—is, that our texts implicate many more meanings than tradition may have supposed.

In my opinion there can be little doubt that the official transmission of texts in Mesopotamia was supplemented by a wealth of oral tradition. Indeed, the situation may be comparable to the one attested in the (still) living oral tradition on Enoch in the Balkanian vernaculars.”

This Akkadian clay tablet, dated to circa 1900-1600 BCE, preserves a partial version of the Sumerian Legend of Etana.

Held by the Morgan Library.

http://www.codex99.com/typography/1.html

(See G.J. Selz, “Die Etana-Erzählung: Ursprung und Tradition eines der ältesten epischen Texte in einer semitischen Sprache,” Acta Sumerologica (Japan) 20 (1998): pp. 135-79.

A different opinion is expressed by P. Steinkeller, “Early Semitic Literature and Third Millennium Seals with Mythological Motifs,” in Literature and Literary Language at Ebla (ed. P. Fronzaroli; Quaderni di Semitistica 18; Florence: Dipartimento di linguistica Università di Firenze, 1992), pp. 243-75 and pls. 1-8.

Further remarks on the ruler’s ascension to heaven are discussed by G.J. Selz, “Der sogenannte ‘geflügelte Tempel’ und die ‘Himmelfahrt’ der Herrscher: Spekulationen über ein ungelöstes Problem der altakkadischen Glyptik und dessen möglichen rituellen Hintergrund,” in Studi sul Vicino Oriente Antico dedicati alla memoria di Luigi Cagni (ed. S. Graziani; Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 2000, pp. 961-83.)

Gebhard J. Selz, “Of Heroes and Sages–Considerations of the Early Mesopotamian Background of Some Enochic Traditions,” in Armin Lange, et al, The Dead Sea Scrolls in Context, v. 2, Brill, 2011, pp. 799-800.