Green Defines Numerous Figures

“After the lahmu, the text goes on to prescribe a type whose name is lost in the break but which is to be inscribed “Go out death, come in life!” Rittig has already pointed out, on the basis of figurines from Aššur, that this is the creature called in modern literature the “bull-man.” (F.A.M. Wiggermann has suggested to me the possible Akkadian name kusarikku; … Reade, BaM 10 (1979), 40).

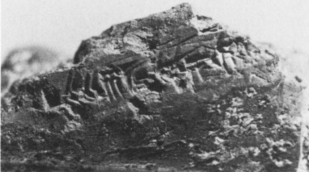

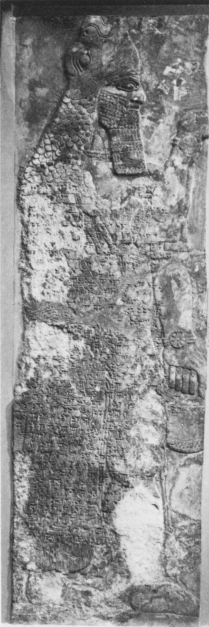

ND 4114. Sun-dried clay figurine of “bull-man” type discovered together with a “spearman” in a foundation box at the W. jamb of the S.E. doorway of court 18 of the Burnt Palace at Nimrud. Previously unpublished. Plate XIVa.

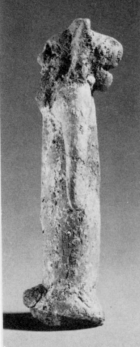

Plate XIVa shows a Burnt Palace example, with obvious taurine hindquarters, and Plate XIIId a rather different type from Fort Shalmaneser, broken but still with fairly clear bull’s legs; the latter was probably inscribed in the same fashion as the Aššur examples and as ritually prescribed.

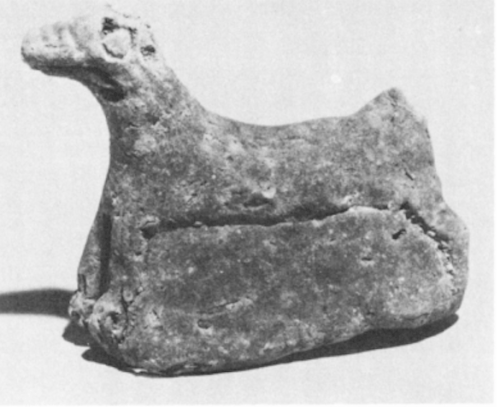

ND 9523 (IM 65138), British School of Archeology in Iraq, photograph by David A. Loggie. Plate XIIId.

Sun-dried clay figurine of “bull-man” type, discovered in a foundation box on the E. side of the N.E. courtyard, at the N. jamb of the doorway leading to room NE 21, Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud. Previously unpublished. Cf. D. Oates, Iraq 23 (1961), 14.

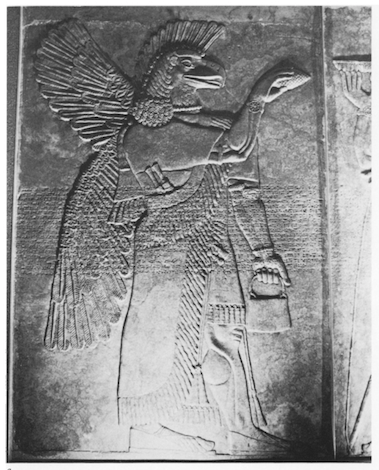

The being is apparently unknown in extant Assyrian monumental sculpture, but can be seen at Pasargadae with the fish-apkallū (Plate XIVc, placed second from the bottom for reasons of formatting), perhaps copied from an Assyrian or Babylonian original; the discovery of the fish-cloaked figure and a “bull-man” together on reliefs at Nineveh is referred to in a letter of Rassam to Rawlinson (quoted by Barnett, SNPAN, 42).

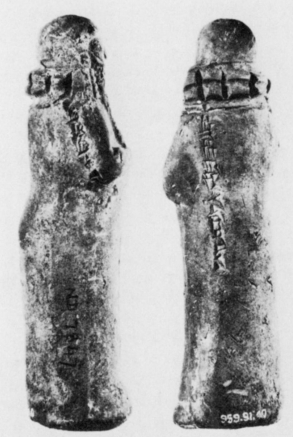

A type superficially resembling the “bull-man” but with some important iconographic distinctions and a different inscription is the figure of Plate XIIIc.

ND 7901. Sun-dried clay figurine of a scorpion-tailed, bird-footed human creature, discovered with figures of other types in the fill of room SE 5 of Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud. Plate XIIIc.

The legs end in bird talons, and on the reverse (Plate XIVb) a curving ridge, formed by pressing the wet clay between the thumb and forefinger, would appear to represent a twisting scorpion-tail.

ND 7901. Sun-dried clay figurine of a scorpion-tailed, bird-footed creature, discovered with figures of other types in the fill of room SE 5 of Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud. Reverse of Plate XIIIc. This image is Plate XIVb.

The type would seem, therefore, to be analogous to a scorpion-tailed figure on an Assyrian relief who has the hindquarters and claws of a bird. This creature has been identified as the girtablīlu, “Scorpion-man;” but the inscription on the Nimrud figure may possibly correspond to that prescribed in the ritual for the type immediately after the bull-legged being, while for the girtablīlu no inscription is ordained. Unfortunately the Akkadian name is again lost.

After figures of snakes, whose identification is obvious enough, the ritual mentions figurines of the well-known mušhuššu, which is surely represented by the creature of Plate XIVd, regarded by the excavators as a dog.

ND 8194 (MMA 59.107.27). Sun-dried clay figurine of a mušhuššu, discovered in the same foundation box as the figure of Plate XIa. Previously published: D. Oates, Iraq 21 (1959), Mallowan, N&R II. Double-catalogued by Rittig. Plate XIVd.

The following prescriptions are for figures of the suhurmaššu, “Goat-fish” and kulīlu, “Fish-man,” rare types which do not occur at Nimrud, and are illustrated here by examples probably from Aššur, Plate XV. Their identities are indicated by comparison of the prescribed legends with actual inscriptions.

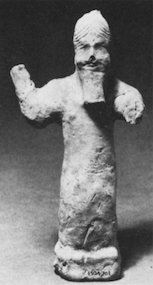

Sowie Museum 9-1796, sun-dried clay figurine of a suhurmaššu, probably from Aššur. Previously published: H.F. Lutz, University of California Publications in Semitic Philology 9/7 (1930), Rittig, 97.

Sowie Museum 9-1795, sun-dried figurine of a kilīlu, allegedly from Aššur. Previously published: Lutz, op. cit., Rittig, 95f. Plate XV.

A little later in the ritual appears the urmahlīlu, “Lion-man,” who has already been identified directly from the inscription on a bas-relief; it is the creature called in modern literature a “lion-centaur.”

After the urmahlīlu, the ritual prescribes clay figures of dogs, an actual set of which, inscribed and colored in close conformity to the prescription, was discovered by Loftus in a rectangular niche at the base of a sculptured doorway slab in the North Palace at Nineveh.

Relief at Pasargadae, in situ. Palace S. photograph by Dr. M.R. Edwards, Plate XIVc.

Limestone relief at one jamb of a doorway of Palace S. at Pasargadae. Achaemenid period. Previously published: D. Stronach, Pasargadae (Oxford 1978), Pl. 59.

Such clay dogs appear not to occur among the Nimrud figures, although seven copper or bronze examples, of differing breeds, sitting and standing, were found in the North-West Palace (Plate XIVe). These metal models have also been considered apotropaic, although there is no absolute proof, and the Nimrud examples were found out of context at the bottom of a well.

ND 3209. Copper or bronze figurine of a dog, discovered with six others down a well at the S. end of room NN of the N.W. Palace at Nimrud. Left ear chipped, and tip of tail broken in antiquity. Previously unpublished: see J.E. Curtis, Dissertation, II; Cf. also Mallowan, ILN 1952; Iraq 15 (1953); N&R I, 103. Plate XIVe.

It does seem possible, therefore, to identify a number of the creatures of Assyrian religious art on the basis of these figurines and their rituals, and to this process the Nimrud figurines, while they do not show the same typological diversity as those from Aššur, are able to make a number of significant contributions.”

Anthony Green, “Neo-Assyrian Apotropaic Figures,” Iraq, Vol. 45, 1983, pp. 92-4.