Kvanvig: Berossos and Primeval History

“Berossos does not only list the sages in succession. He is especially interesting because of the information he gives about the first sage, Oannes, who parallels Uan in the two other lists. Berossos’ account is here so noteworthy that we quote it as a whole:

“In Babylonia there was a large number of people of different ethnic origins who had settled in Chaldea. They lived without discipline and order, just like animals.

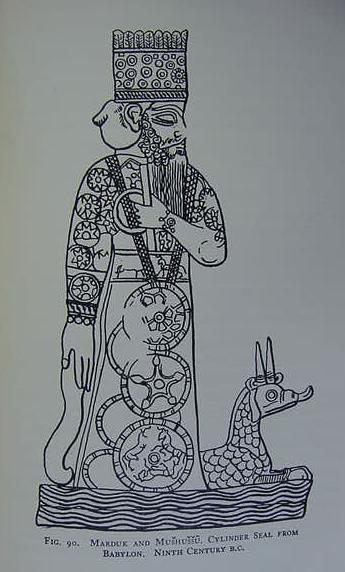

In the very first year there appeared from the Red Sea (the Persian Gulf) in an area bordering Babylonia a frightening monster named Oannes, just as Apollodoros says in his history.

It had the whole body of a fish, but underneath and attached to the head of the fish there was another head, human, and joined to the tail of the fish, feet, like those of a man, and it had a human voice.

Its form has been preserved in sculpture to this day.

Berossos says that this monster spent its days with men, never eating anything, but teaching men the skills necessary for writing and for doing mathematics and for all sorts of knowledge: how to build cities, found temples, and make laws.

It taught men how to determine borders and divide land, also how to plant seeds and then harvest their fruits and vegetables. In short, it taught men all those things conducive to a stalled and civilized life.

Since that time nothing further has been discovered.

At the end of the day, this monster, Oannes, went back to the sea and spent the night. It was amphibious, able to live both on land and in the sea.

Later also other monsters similar to Oannes appeared, about whom Berossos gave more information in his writings on the kings. Berossos says about Oannes that he had written as follows about the creation and government of the world and had given these explanations to man.”

(A creation story based on Enuma Elish follows.)

(Eusebius, (Arm.) Chronicles, p.6, 8-9, 2 and Syncellus p. 49, 19).

It is not difficult to recognize the Sumerian concept of civilization in Berossos’ account. We have met this several times earlier in the way it also permeated some of the Babylonian literature.

Fish-man known as a Kulullû. Terracotta figurine (8th-7th BCE) in the Louvre collection, Nr. 3337.

The Kulullû is distinct from the fish-Apkallū. They are not the same.

In Atrahasis we met it in the relation between the lullû-man and the ilu-man. In the Eridu Genesis we met in it the description of human’s first uncivilized state, before the gods had given the human race kingship and they had established cities.

Sowie Museum 9-1796, sun-dried clay figurine of a suhurmaššu, probably from Aššur. Previously published: H.F. Lutz, University of California Publications in Semitic Philology 9/7 (1930), Rittig, 97.

Sowie Museum 9-1795, sun-dried figurine of a kilīlu, allegedly from Aššur. Previously published: Lutz, op. cit., Rittig, 95f. Plate XV.

In the Royal Chronicle of Lagash this wrecked state of humankind was transposed to the period after the destruction by the flood. In condensed form, we find it in the Sumerian concept of me, which is linked to the names of both antediluvian kings and sages.

In many ways Berossos’ account is a description of how the me first was bestowed on the human race after they had lived like animals.

In the sources we have dealt with so far, Berossos is the first who explicitly combines the tradition of the apkallus with other blocks of tradition from primeval time. This may be suggested in Bīt Mēseri in the transition from the seven to the four sages, but it is not explicitly stated.”

Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011, pp. 113-4.