“For those who hold that the Grail story is essentially, and fundamentally, Christian, finding its root in Eucharistic symbolism, the title is naturally connected with the use of the Fish symbol in early Christianity: the Icthys anagram, as applied to Christ, the title ‘Fishers of Men,’ bestowed upon the Apostles, the Papal ring of the Fisherman–though it must be noted that no manipulation of the Christian symbolism avails satisfactorily to account for the lamentable condition into which the bearer of the title has fallen.” 2

So far as the present state of our knowledge goes we can affirm with certainty that the Fish is a Life symbol of immemorial antiquity, and that the title of Fisher has, from the earliest ages, been associated with Deities who were held to be specially connected with the origin and preservation of Life.

In Indian cosmogony Manu finds a little fish in the water in which he would wash his hands; it asks, and receives, his protection, asserting that when grown to full size it will save Manu from the universal deluge. This is Jhasa, the greatest of all fish. 1

The first Avatar of Vishnu the Creator is a Fish. At the great feast in honour of this god, held on the twelfth day of the first month of the Indian year, Vishnu is represented under the form of a golden Fish, and addressed in the following terms:

“Wie Du, O Gott, in Gestalt eines Fisches die in der Unterwelt befindlichen Veden gerettet hast, so rette auch mich 2.”

The Fish Avatar was afterwards transferred to Buddha.

In Buddhist religion the symbols of the Fish and Fisher are freely employed. Thus in Buddhist monasteries we find drums and gongs in the shape of a fish, but the true meaning of the symbol, while still regarded as sacred, has been lost, and the explanations, like the explanations of the Grail romances, are often fantastic afterthoughts.

In the Māhāyana scriptures Buddha is referred to as the Fisherman who draws fish from the ocean of Samsara to the light of Salvation. There are figures and pictures which represent Buddha in the act of fishing, an attitude which, unless interpreted in a symbolic sense, would be utterly at variance with the tenets of the Buddhist religion. 1

This also holds good for Chinese Buddhism. The goddess Kwanyin (= Avalokiteśvara), the female Deity of Mercy and Salvation, is depicted either on, or holding, a Fish.

In the Han palace of Kun-Ming-Ch’ih there was a Fish carved in jade to which in time of drought sacrifices were offered, the prayers being always answered.

Both in India and China the Fish is employed in funeral rites. In India a crystal bowl with Fish handles was found in a reputed tomb of Buddha.

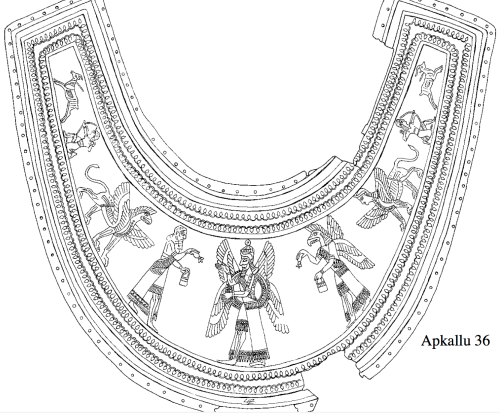

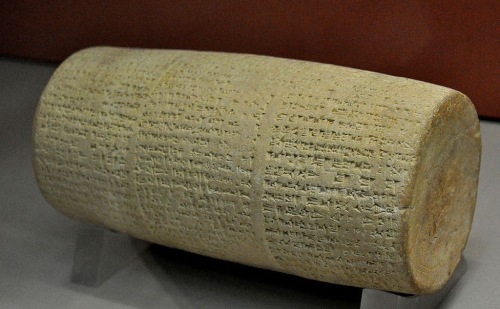

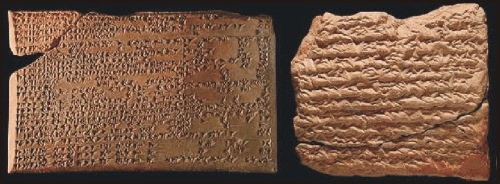

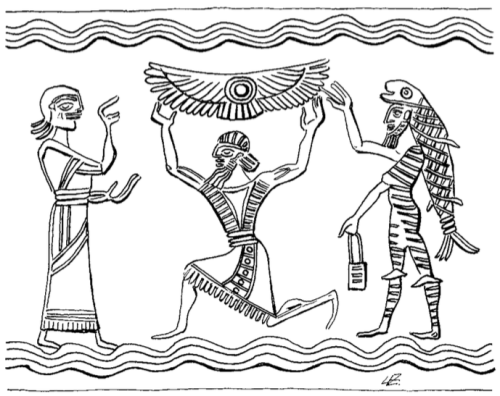

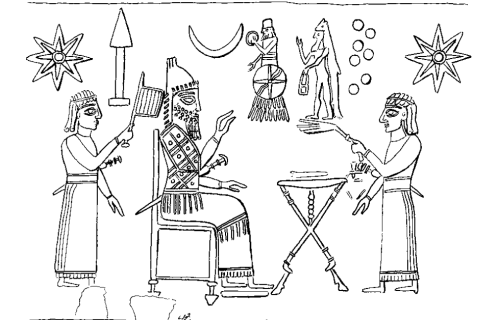

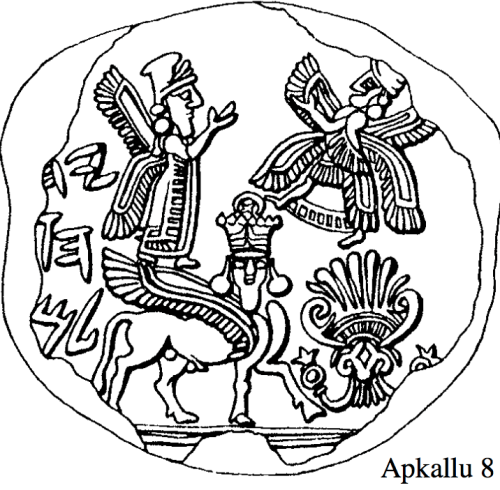

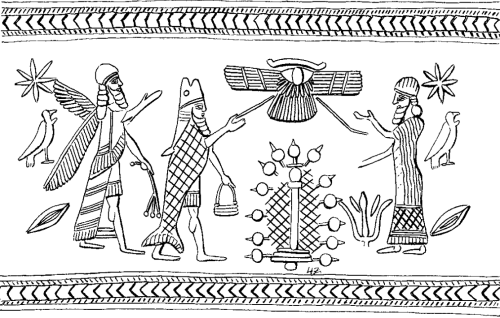

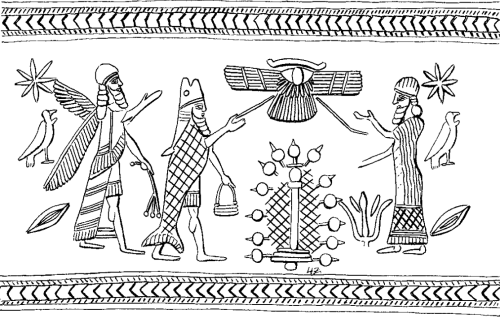

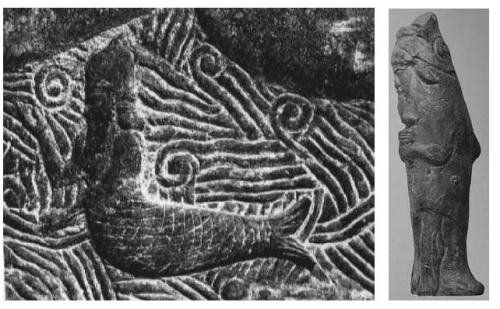

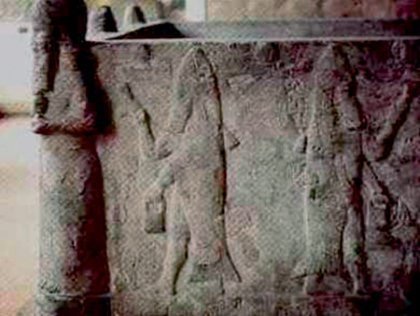

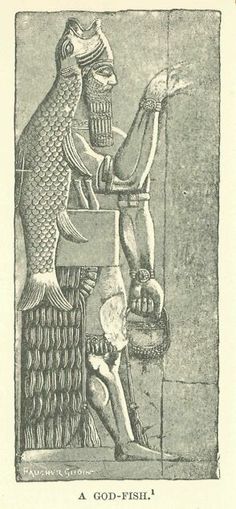

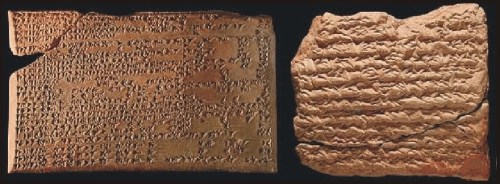

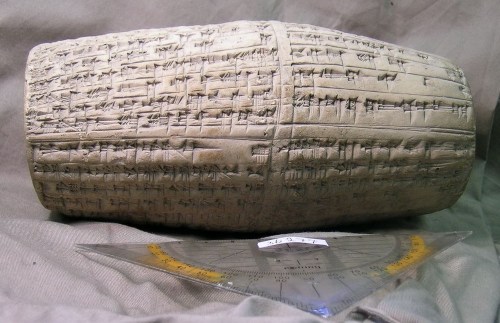

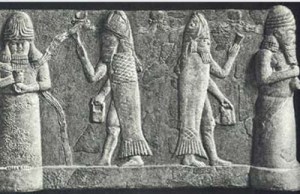

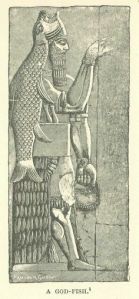

In China the symbol is found on stone slabs enclosing the coffin, on bronze urns, vases, etc. Even as the Babylonians had the Fish, or Fisher, god, Oannes who revealed to them the arts of Writing, Agriculture, etc., and was, as Eisler puts it, ‘teacher and lord of all wisdom,’ so the Chinese Fu-Hi, who is pictured with the mystic tablets containing the mysteries of Heaven and Earth, is, with his consort and retinue, represented as having a fish’s tail 2.

The writer of the article in The Open Court asserts that “the Fish was sacred to those deities who were supposed to lead men back from the shadows of death to life 3.”

If this be really the case we can understand the connection of the symbol first with Orpheus, later with Christ, as Eisler remarks:

“Orpheus is connected with nearly all the mystery, and a great many of the ordinary chthonic, cults in Greece and Italy. Christianity took its first tentative steps into the reluctant world of Graeco-Roman Paganism under the benevolent patronage of Orpheus.” 1

There is thus little reason to doubt that, if we regard the Fish as a Divine Life symbol, of immemorial antiquity, we shall not go very far astray.

We may note here that there was a fish known to the Semites by the name of Adonis, although as the title signifies ‘Lord,’ and is generic rather than specific, too much stress cannot be laid upon it.

It is more interesting to know that in Babylonian cosmology Adapa the Wise, the son of Ea, is represented as a Fisher. 2

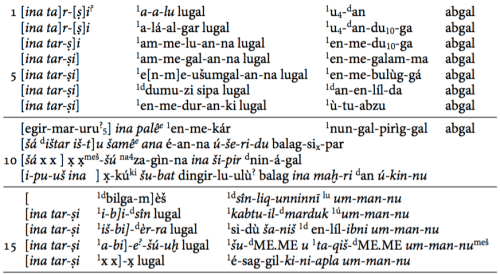

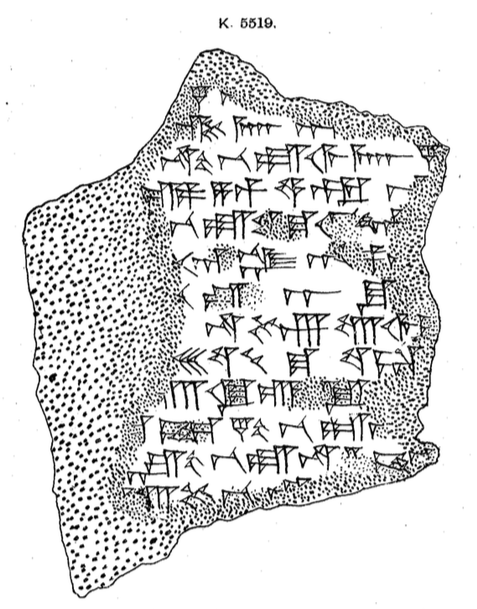

In the ancient Sumerian laments for Tammuz, previously referred to, that god is frequently addressed as Divine Lamgar, Lord of the Net, the nearest equivalent I have so far found to our ‘Fisher King.’ 3

Whether the phrase is here used in an actual or a symbolic sense the connection of idea is sufficiently striking.

In the opinion of the most recent writers on the subject the Christian Fish symbolism derives directly from the Jewish, the Jews, on their side having borrowed freely from Syrian belief and practice. 4

What may be regarded as the central point of Jewish Fish symbolism is the tradition that, at the end of the world, Messias will catch the great Fish Leviathan, and divide its flesh as food among the faithful.

As a foreshadowing of this Messianic Feast the Jews were in the habit of eating fish upon the Sabbath. During the Captivity, under the influence of the worship of the goddess Atargatis, they transferred the ceremony to the Friday, the eve of the Sabbath, a position which it has retained to the present day.

Eisler remarks that “in Galicia one can see Israelite families in spite of their being reduced to the extremest misery, procuring on Fridays a single gudgeon, to eat, divided into fragments, at night-fall.

In the 16th century Rabbi Solomon Luria protested strongly against this practice. Fish, he declared, should be eaten on the Sabbath itself, not on the Eve.” 1

This Jewish custom appears to have been adopted by the primitive Church, and early Christians, on their side, celebrated a Sacramental Fish-meal. The Catacombs supply us with numerous illustrations, fully described by the two writers referred to.

The elements of this mystic meal were Fish, Bread, and Wine, the last being represented in the Messianic tradition: “At the end of the meal God will give to the most worthy, i.e., to King David, the Cup of Blessing–one of fabulous dimensions.” 2

Fish play an important part in Mystery Cults, as being the ‘holy’ food. Upon a tablet dedicated to the Phrygian Mater Magna we find Fish and Cup; and Dölger, speaking of a votive tablet discovered in the Balkans, says, “Hier ist der Fisch immer und immer wieder allzu deutlich als die heilige Speise eines Mysterien-Kultes hervorgehoben.” 3

Now I would submit that here, and not in Celtic Folk-lore, is to be found the source of Borron’s Fish-meal. Let us consider the circumstances. Joseph and his followers, in the course of their wanderings, find themselves in danger of famine. The position is somewhat curious, as apparently the leaders have no idea of the condition of their followers till the latter appeal to Brons. 1

Brons informs Joseph, who prays for aid and counsel from the Grail. A Voice from Heaven bids him send his brother-in-law, Brons, to catch a fish.

Meanwhile he, Joseph, is to prepare a table, set the Grail, covered with a cloth, in the centre opposite his own seat, and the fish which Brons shall catch, on the other side.

He does this, and the seats are filled–“Si s’i asieent une grant partie et plus i ot de cels qui n’i sistrent mie, que de cels qui sistrent.”

Those who are seated at the table are conscious of a great “douceur,” and “l’accomplissement de lor cuers,” the rest feel nothing.

Now compare this with the Irish story of the Salmon of Wisdom 2.

Finn Mac Cumhail enters the service of his namesake, Finn Eger, who for seven years had remained by the Boyne watching the Salmon of Lynn Feic, which it had been foretold Finn should catch.

The younger lad, who conceals his name, catches the fish. He is set to watch it while it roasts but is warned not to eat it. Touching it with his thumb he is burned, and puts his thumb in his mouth to cool it.

Immediately he becomes possessed of all knowledge, and thereafter has only to chew his thumb to obtain wisdom.

Mr Nutt remarks: “The incident in Borron’s poem has been recast in the mould of mediaeval Christian Symbolism, but I think the older myth can still be clearly discerned, and is wholly responsible for the incident as found in the Conte du Graal.”

But when these words were written we were in ignorance of the Sacramental Fish-meal, common alike to Jewish, Christian, and Mystery Cults, a meal which offers a far closer parallel to Borron’s romance than does the Finn story, in which, beyond the catching of a fish, there is absolutely no point of contact with our romance, neither Joseph nor Brons derives wisdom from the eating thereof; it is not they who detect the sinners, the severance between the good and the evil is brought about automatically.

The Finn story has no common meal, and no idea of spiritual blessings such as are connected therewith.

In the case of the Messianic Fish-meal, on the other hand, the parallel is striking; in both cases it is a communal meal, in both cases the privilege of sharing it is the reward of the faithful, in both cases it is a foretaste of the bliss of Paradise.

Furthermore, as remarked above, the practice was at one time of very widespread prevalence.

Now whence did Borron derive his knowledge, from Jewish, Christian or Mystery sources?

This is a question not very easy to decide. In view of the pronounced Christian tone of Borron’s romance I should feel inclined to exclude the first, also the Jewish Fish-meal seems to have been of a more open, general and less symbolic character than the Christian; it was frankly an anticipation of a promised future bliss, obtainable by all.

Orthodox Christianity, on the other hand, knows nothing of the Sacred Fish-meal, so far as I am aware it forms no part of any Apocalyptic expectation, and where this special symbolism does occur it is often under conditions which place its interpretation outside the recognized category of Christian belief.

A noted instance in point is the famous epitaph of Bishop Aberkios, over the correct interpretation of which scholars have spent much time and ingenuity. 1 In this curious text Aberkios, after mentioning his journeys, says:

“Paul I had as my guide,

Faith however always went ahead and set before me as food a Fish from a Fountain, a huge one, a clean one,

Which a Holy Virgin has caught.

This she gave to the friends ever to eat as food,

Having good Wine, and offering it watered together with Bread.”

Aberkios had this engraved when 72 years of age in truth.

Whoever can understand this let him pray for Aberkios.”

Eisler (I am here quoting from the Quest article) remarks, “As the last line of our quotation gives us quite plainly to understand, a number of words which we have italicized are obviously used in an unusual, metaphorical, sense, that is to say as terms of the Christian Mystery language.”

While Harnack, admitting that the Christian character of the text is indisputable, adds significantly: “aber das Christentum der Grosskirche ist es nicht.”

Thus it is possible that, to the various points of doubtful orthodoxy which scholars have noted as characteristic of the Grail romances, Borron’s Fish-meal should also be added.

Should it be objected that the dependence of a medieval romance upon a Jewish tradition of such antiquity is scarcely probable, I would draw attention to the Voyage of Saint Brandan, where the monks, during their prolonged wanderings, annually ‘kept their Resurrection,’ i.e., celebrate their Easter Mass, on the back of a great Fish. 1

On their first meeting with this monster Saint Brandan tells them it is the greatest of all fishes, and is named Jastoni, a name which bears a curious resemblance to the Jhasa of the Indian tradition cited above. 2

In this last instance the connection of the Fish with life, renewed and sustained, is undeniable.

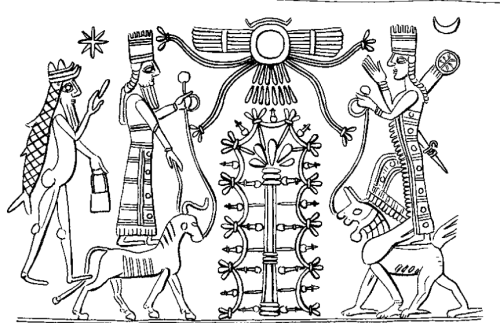

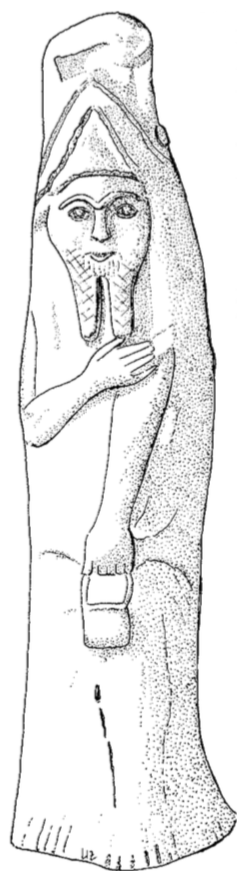

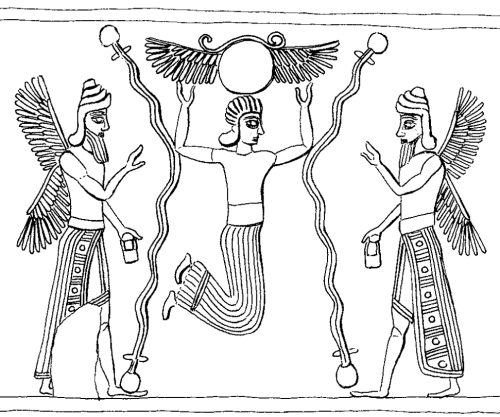

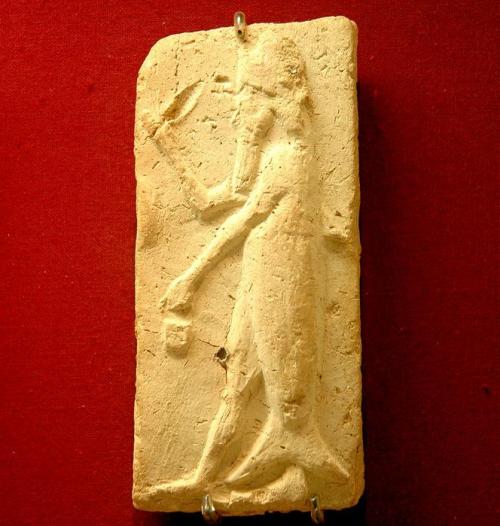

The original source of such a symbol is most probably to be found in the belief, referred to in a previous chapter, 1 that all life comes from the water, but that a more sensual and less abstract idea was also operative appears from the close connection of the Fish with the goddess Astarte or Atargatis, a connection here shared by the Dove.

Cumont, in his Les Religions Orientales dans le Paganisme Romain, says:

“Two animals were held in general reverence, namely, Dove and Fish.

Countless flocks of Doves greeted the traveller when he stepped on shore at Askalon, and in the outer courts of all the temples of Astarte one might see the flutter of their white wings.

The Fish were preserved in ponds near to the Temple, and superstitious dread forbade their capture, for the goddess punished such sacrilege, smiting the offender with ulcers and tumours.” 2

But at certain mystic banquets priests and initiates partook of this otherwise forbidden food, in the belief that they thus partook of the flesh of the goddess. “

Jessie L. Weston, From Ritual to Romance, 1920, pp. 118-26.