I

I apologize for the length of this piece (5,187 words), but bear with me: An article leapt out at me from my academia.edu feed: Tzahi Weiss, “On the Matter of Language: The Creation of the World from Letters and Jacques Lacan’s Perception of Letters as Real,” 2009.

I read it. But I did not just stumble across it. Something is sending me smoke signals. The multiverse. Perhaps God. Or my subconscious. I was stuck on chapter 22 of my Grenada book for the past week. Then divine intervention struck. Surprised and alarmed, I combined sleep and coffee and alchemy ensued.

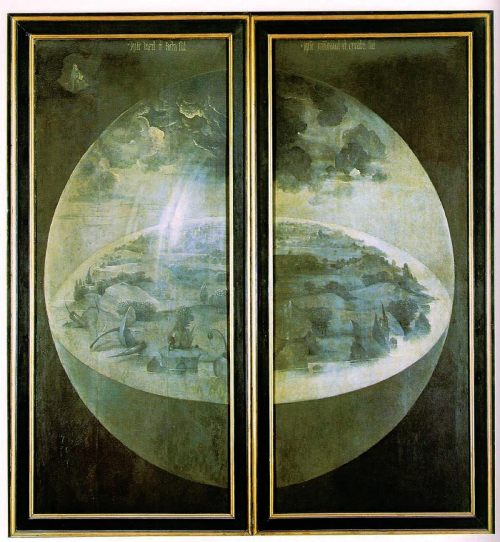

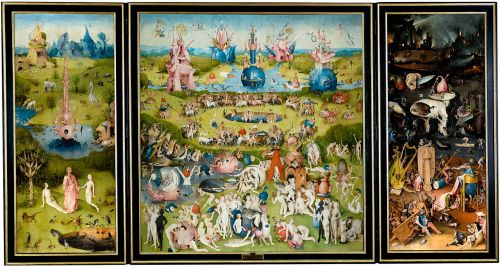

I am obsessed by the idea that we project reality through a mass delusion, shared consciousness, a form of hypnotic dreaming that generates everything in our multiverse. Genesis asserts that God spoke the world into existence: “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.”

The idea that the mind, or consciousness, creates reality through language merely changes the protagonists and specifies the method. We do it, dreaming as a species, or as conscious entities, which would permit even trees and insects, anything conscious, to participate.

Perhaps God does it, in His imponderable slumber. But whom hypnotizes whom? Did God set us all to dreaming, are we all, humans, animals, insects, plants, in a collective waking trance? Or did we lull Him to eternal sleep? And is it truly eternal? What happens when God wakes up?

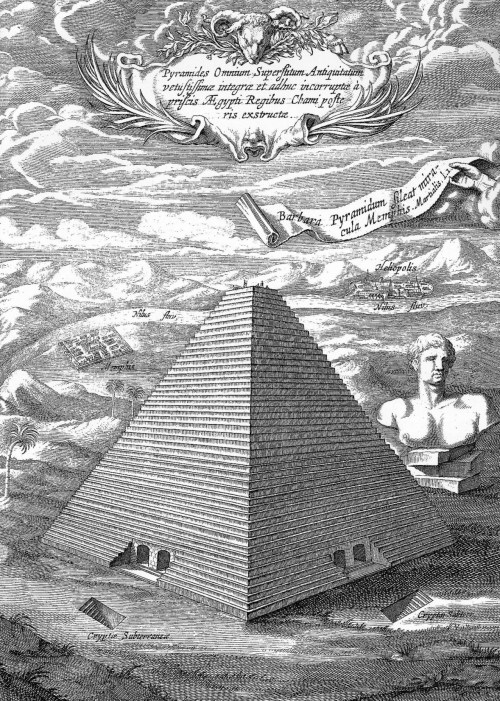

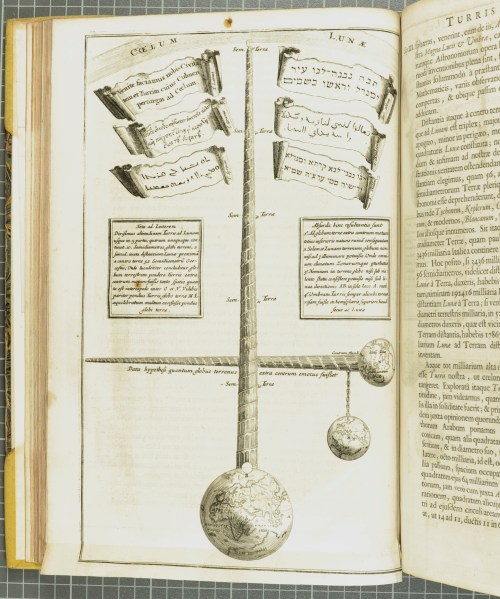

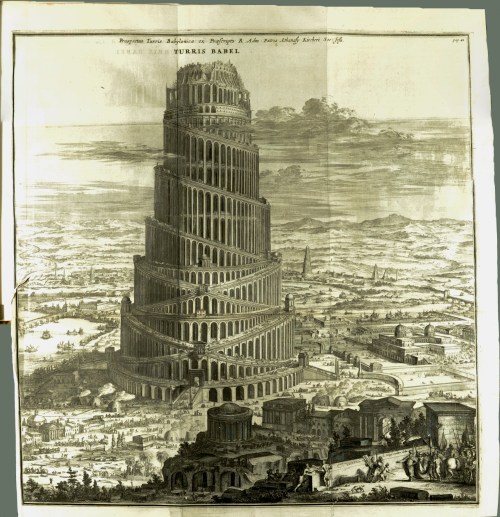

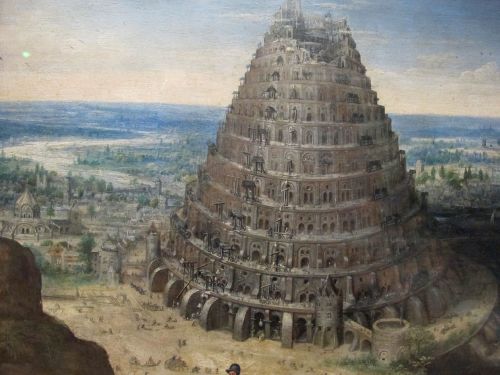

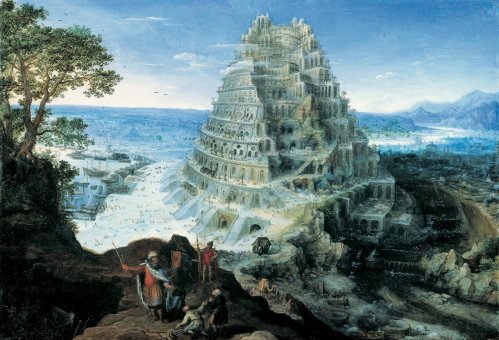

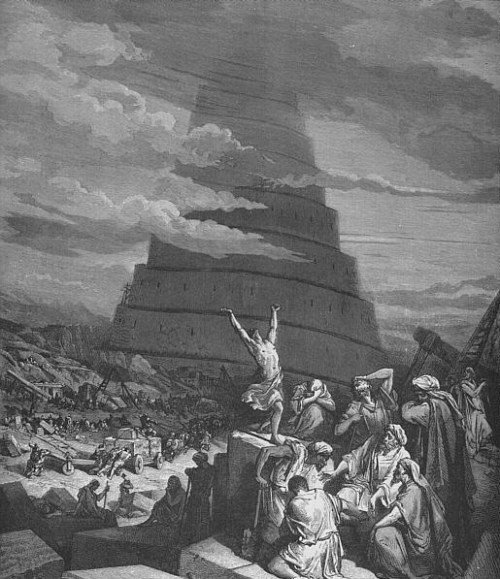

Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530-1569 CE), The Tower of Babel. Brueghel painted three versions of the Tower of Babel. One is kept in the Museum Bojimans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the second, this one, is held in the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna, while the disposition of the third version, a miniature on ivory, is unknown. Faithful reproductions of two-dimensional public domain works of art are public domain.

But what of the Tower of Babel, you say? Languages are just software. DNA programming for the wetware of species on one planet, a miraculous mote in the immensity of creation.

Dogs and cats have language, so do dolphins and whales. Do you not hear the screaming of the trees? Insects communicate. My wife reminded me that humans use just ten percent of our brain capacity. What is the other ninety percent doing?

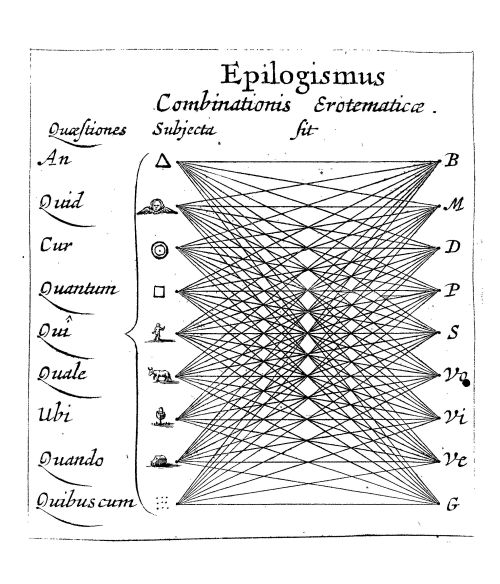

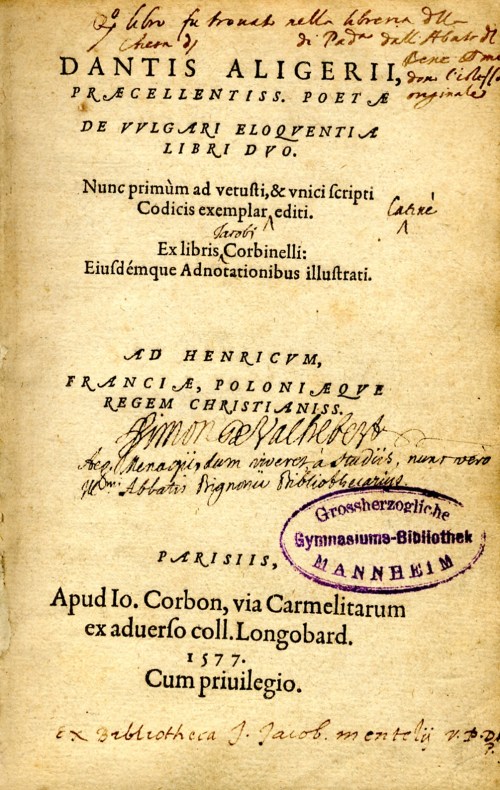

Tzahi Weiss dates the “myth” of the creation of the world from alphabetic letters to the 1st Millennium CE. I think that working on my pet project, Samizdat, shook my brain loose. I uploaded a new post last night.

Then Jorge Luis Borge’s 1964 story about Léon Bloy, “The Mirror of Enigmas,” crossed my path, and I knew that something was nudging me in a particular direction.

I now know how to organize the chapter headings of my book. The multiverse told me. I dreamt about it all night long.

Citing de Quincey, Borges writes:

“Even the articulate or brutal sounds of the globe must be all so many languages and ciphers that all have their corresponding keys — have their own grammar and syntax; and thus the least things in the universe must be secret mirrors to the greatest.”

Which reminded me of Blake’s immortal Auguries of Innocence:

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour”

Then Borges quotes Cipriano de Valra, translating Saint Paul: Videmus nunc per speculum in aenigmate: tunc autem facie ad faciem. Nunc cognosco ex parte: tunc autem cognoscam sicut et cognitus sum.

I prefer the Authorized King James Version (AKJV) of 1 Corinthians 13:12: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part, but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

What? I know. Bear with me.

It is important to recall the entirety of 1 Corinthians 13, if only for context:

“13 Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

2 And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing.

3 And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing.

4 Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up,

5 doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil;

6 rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth;

7 beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things.

8 Charity never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease; whether there be knowledge, it shall vanish away.

9 For we know in part, and we prophesy in part.

10 But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part shall be done away.

11 When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

12 For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

13 And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.”

For 1 Corinthians 13:12 is infamous, the temptation to cite it without its accompanying sentences to mean whatever you like is manifestly irresistible.

Apropos of nothing, I remember that only forty seven of the fifty four translators designated by King James I actually worked on the AKJV, which issued in 1611 CE.

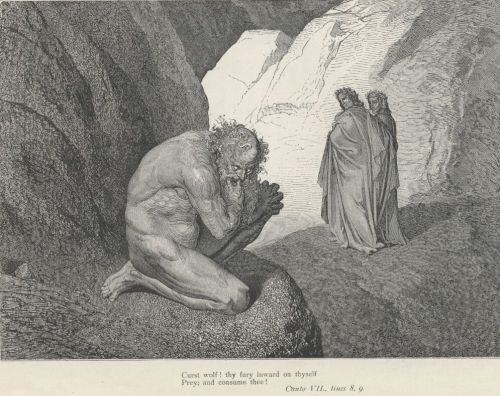

Continuing, Borges translates Léon Bloy, who shockingly mused:

“The statement by St Paul: Videmus nunc per speculum in aenigmate would be a skylight through which one might submerge himself in the true Abyss, which is the soul of man.

The terrifying immensity of the firmament’s abyss is an illusion, an external reflection of our own abysses, perceived “in a mirror.”

We should invert our eyes and practice a sublime astronomy in the infinitude of our hearts, for which God was willing to die…

If we see the Milky Way, it is because it actually exists in our souls.”

I remember first encountering Borges as a teenager in high school almost 40 years ago. Somebody handed me a copy of Labyrinths, changing my life. Borge’s erudition astonished me. I was staggered by his subject matter and his mastery of short story and essay formats, writing no novels. I was an amateur metaphysician in those days, and some will think that I still am. I am now, however, more witting about the messages that the multiverse sends to me.

Leaping ahead, Borges cites a letter written by Bloy in December, 1894 CE:

“Everything is a symbol, even the most piercing pain. We are dreamers who shout in our sleep. We do not know whether the things afflicting us are the secret beginning of our ulterior happiness or not.

We now see, St. Paul maintains, per speculum in aenigmate, literally: “in an enigma by means of a mirror” and we shall not see in any other way until the coming of the One who is all in flames and who must teach us all things.”

The imagery of dreamers shouting in nightmares, enigmas, mirrors, and a Teacher in flames flares in my imagination. Finally, Borges attests that Bloy wrote a book in 1912 CE titled L’Âme de Napoléon, citing just two final passages. The first:

“Every man is on earth to symbolize something he is ignorant of and to realize a particle or a mountain of the invisible materials that will serve to build the City of God.”

The second is used by Borges in at least two stories:

“There is no human being on earth capable of declaring with certitude who he is. No one knows what he has come into this world to do, what his acts correspond to, his sentiments, his ideas, or what his real name is, his imperishable Name in the register of Light …

History is an immense liturgical text where the iotas and the periods are worth no less than the entire versicles or chapters, but the importance of one or the other is indeterminable and profoundly hidden.”

This is Kabbalah, but there is no indication that Bloy knew. Borges, though, has read all books. In an echoing piece written in 1951, “On the Cult of Books,” Borges confirms:

“The world, according to Mallarmé exists for a book; according to Bloy, we are the versicles or words or letters of a magic book, and that incessant book is the only thing in the world: more exactly, it is the world.”

Borges concludes:

Bloy related to “the whole of Creation the method which the Jewish Cabalists applied to the Scriptures. They thought that a work dictated by the Holy Spirit was an absolute text: in other words, a text in which the collaboration of chance was calculable as zero.”

This portentous premise of a book impenetrable to contingency, of a book which is a mechanism of infinite purposes … moved them to exegetical rigors … Their excuse is that nothing can be contingent in the work of an infinite mind.

Léon Bloy postulates this hieroglyphical character — this character of a divine writing, an angelic cryptography —at all moments and in all beings on earth.”

This preposterous thesis rings true to me, which makes Borge’s summation of Bloy brutal:

“No man knows who he is, affirmed Léon Bloy. No one could illustrate the intimate ignorance better than he. He believed himself a rigorous Catholic and he was a continuer of the Cabalists, a secret brother of Swedenborg and Blake: heresiarchs.”

Indeed. Bloy is every man, and we are all Bloy. Secret brothers of Swedenborg, Shelley, and Blake, who unforgettably noted that John Milton was on the side of the fallen angels. Heresiarchs.

(Jorge Luis Borges, “The Mirror of Enigmas,” Labyrinths, Penguin, 1964. Translated by James E. Irby. For “On the Cult of Books,” see Selected Non-Fictions, Penguin, 1999.

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790 CE, object 6 (Bentley 6, Erdman 6, Keynes 6). The Blake Archive’s note on this etching states that Blake’s name as the publisher is “nowhere stated in the work, but the attribution is certain.” Acquired from Francis Douce in 1834 by the Bodleian Library, this etching is held in the Rare Books Department in the Douce Collection under Accession Number: Arch. G d.53. http://www.blakearchive.org/exist/blake/archive/copyinfo.xq?copyid=mhh.b

William Blake observed, “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”

Again, it is vital to read the surrounding text, as Blake has more to say to us. For example, in line 123 of the Bartleby 1908 edition of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake wrote:

“There they were received by Men who occupied the sixth chamber, and took the forms of books and were arranged in libraries.”

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790 CE).

William Blake (1757-1827 CE), God Judging Adam, 1795. Presented by W. Graham Robertson to the Tate Gallery in 1939. This work is in the public domain in the United States, and in those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less.

II

Contemplating these ideas leads to chicken and egg conundrums, but this is a background process for me.

I am always thinking about myself thinking, transfixed by the paradox, so when I trip across something that resonates like this, I wonder. I do not believe in coincidence. I sense synchronicity everywhere.

While reading Weiss, I wrote the following comments.

Jewish writers addressing the creation of reality from language do so in Hebrew, because the topic is best addressed in that language, or because they seek to reserve the subject for themselves. I do not blame them, though I must note that Weiss is one of the worst offenders, with virtually all pertinent papers on his academia.edu page posted in Hebrew.

Joseph Dan (On the Sanctity) and Ithamar Gruenwald (“Letters, Writing, and the Ineffable Name”) are obvious exemplars, though Tzahi Weiss lavishes a long footnote on Elliot R. Wolfson, reproduced below, and acknowledges Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, 1995.

Genesis 1 asserts that God used speech to create the world because of the holiness of the Hebrew language.

Weiss demurs, stating that Judaism holds no monopoly on the sacred, citing Franz Dornseiff’s Das Alphabet in Mystik und Magie.

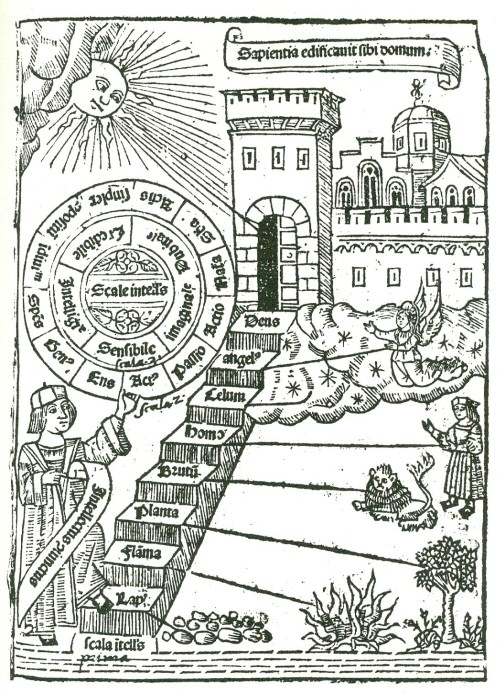

This is, in fact, an old idea, illustrated by the Greek term stoicheion, στοιχείον, which refers to both letters and the physical foundations of the world. Guy Stroumsa, whom I will momentarily cite at length, informs us that stoicheia is, “since Plato at least, the word for “elements,” i.e. ….water, earth, fire and air.”

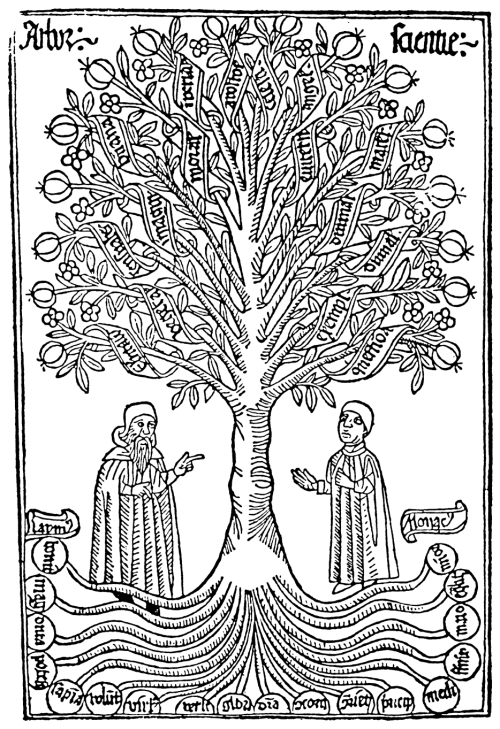

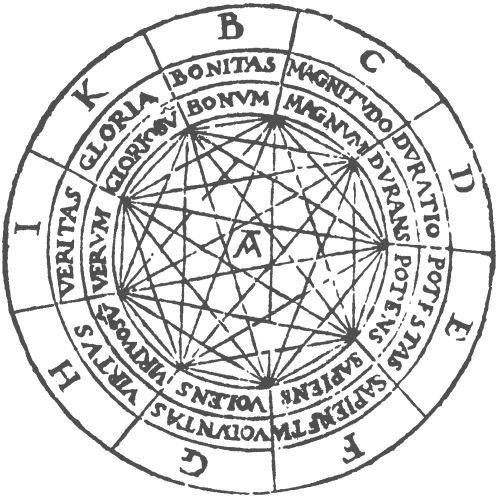

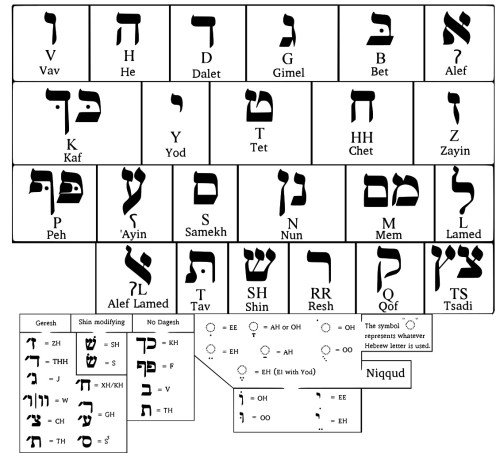

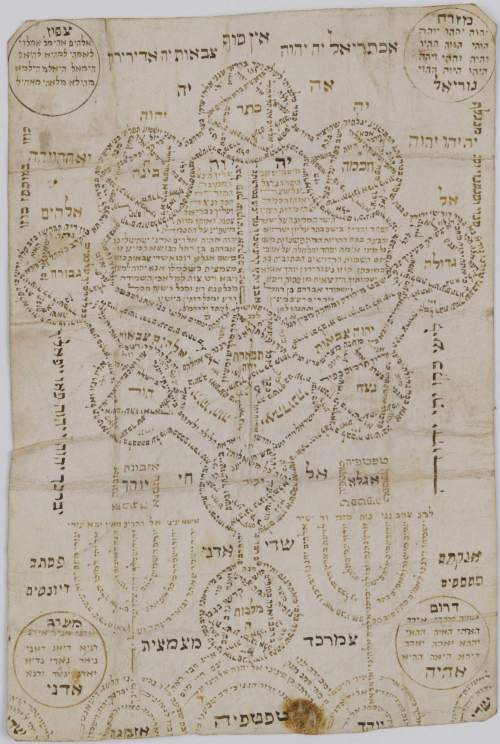

Weiss identifies three traditions, the first deriving from “rabbinic sources, Heikhalot literature and the Samaritan homiletic tractate Memar Marqah,” which claims that God created the world using the letters of the ineffable Name, the Tetragrammaton יהרה.

Weiss states that the second tradition derives from the Sefer Yetsirah, and an obscure tract titled The Mystery of the Greek Letters, attributed to a 6th century Christian monk named Saba or Sabas.

Guy Stroumsa, in “The Mystery of the Greek Letters: A Byzantine Kabbalah?” cites Cordula Bandt, in Der Traktat, who concluded that the attribution to Sabas is pseudepigraphic: “it must have been written by a follower of Sabas, a Melkite (and anti-Origenist) monk in sixth century Palestine.” (Pg. 36).

The second tradition is also reflected in the Memar Marqah, and states that all 22 letters of the Hebrew (or Aramaic) alphabet are required.

The second chapter of Sefer Yetsirah unforgettably begins:

“Twenty-two letters: he carved them out … and formed with them the life of all creation and the life of all that would be formed.” (§20).

The third tradition derives from Gnostic myths that 24 letters created the upper world, also comprising “celestial entities.”

I must again cite Guy Stroumsa:

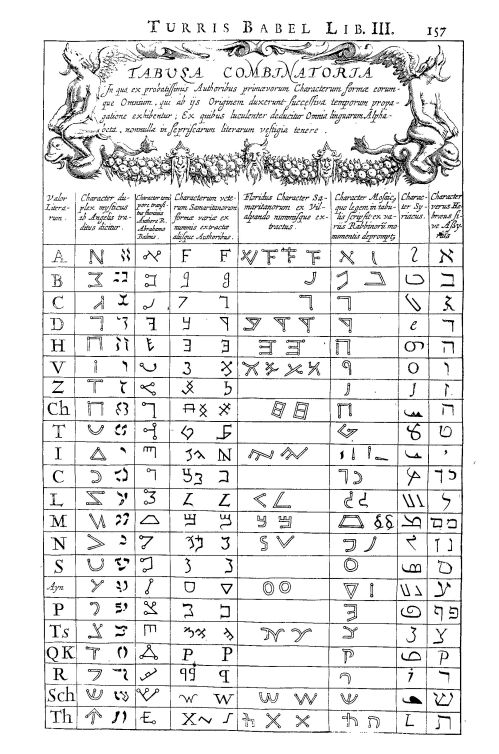

“The mysterion hidden in the letters (stoicheia) was revealed to Sabas by a Power (kratos) “as in ecstasy.” It is with the Greek letters (or characters) that our text deals. These letters were given (by God) “before idolatry” in order to bring humankind to the true cult of God. There are, however, only twenty-two letters in this alphabet, rather than twenty-four of the Greek alphabet!

Χ and Ψ were added later, by…the Hellenic pagan thinkers. The mystery of these letters, we are told, is “hidden since the beginning of the world.” There are twenty-two letters, like the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet, just as there are twenty-two books of the Bible “according to the Jews,” twenty-two works of God in the creation of the world, and twenty-two “marvelous works in the economy of Christ.”

…The seven vocal letters represent the seven hypostaseis of creation: heaven, water, firmament, air, earth, water between the two earths, and inferior earth. Elsewhere in the text, they also represent the seven creatures in possession of a voice. I have dealt elsewhere with the number of seven essential elements, or hypostaseis of creation, arguing that it reflects the seven Iranian Amesha Spenta, later reflected in the first seven Kabbalistic Sefirot.”

After addressing the shapes of the letters themselves, carefully observing that “The four elements, air, fire, earth and water are seen in parallel to the four cardinal points of the universe, the four directions of the wind, the four seasons, and the four great rivers: the Pishon, the Gehon, the Tigris and the Euphrates….” Stroumsa continues:

“Various signs in our text point to Jewish traditions. The most important of these signs, of course, is the number of the letters, which points to the Hebrew –or to the Syriac– alphabet…

This rather clearly points to a Hebrew context of at least the Urtext, or the origin of the exegetical traditions of the letters as they are preserved in our text.

To be sure, the text retains a clearly polemical tone against the Jews, who belong to Satan from the beginning and are called Deicide. Syriac was Adam’s language.

The Syriac letters God himself engraved on a stone tablet, like the Law, with His hand and finger. This tablet, upon which the theosophy was inscribed, was found after the flood by Cadmus, “the Greek philosopher,” and was at the source of science in Palestine and Phoenicia, before the letters reached Greece.” (Pp. 36-7).

These three traditions differ only in the number of letters used in the creation of the universe, though Sefer Yetsirah emphasizes gematria as a paradigm for the 22 Hebrew letters.

This is a colorized version of Camille Flammarion’s woodcut, L’Atmosphere–Météorologie Populaire, Paris, 1888. Colorization was executed by Hugo Heikenwaelder, 1998. I prefer its Spanish name, “imagen de la teoría de la eternidad.” This enigmatic woodcut was not done by Flammarion, he allegedly just commissioned and published it. A missionary peers through the curtained firmament of the earth to perceive the mechanisms of the spheres and the phantasmagoria of the universe. The original caption, “A medieval missionary finds the point where heaven and earth meet,” is attributed to Voltaire. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Universum.jpg

This reminds me of the perplexing revelation that Haaretz, the Israeli newspaper, reported that computer experiments discovered that the letters that form the word “Torah” appear throughout Genesis, “one by one, in strict order, at regular intervals of 49 letters, perfectly integrated into the words that compose the text.” This secret clue was said to be “too complicated to have been thought of by human beings.”

This “secret clue” awaited the conjunction of humans, programs and computers sufficiently sophisticated to expose it, making me wonder what other secrets remain to be discerned, and most of all, it is a clue to what?

(Guy Stroumsa, “The Mystery of the Greek Letters: A Byzantine Kabbalah?” History Religionum, Numero 6, pp. 35-43.

Guy Stroumsa, A Zoroastrian Origin to the Sefirot? in Irano-Judaica 3, 1994, pp. 17-33.

Cordula Bandt, Der Traktat, “Vom Mysterium der Buchstaben.” Kritischer Text mit Einführung, Übersetzung und Anmerkungen, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2007, and “The Alphabet as “Henotikon.” The Tract “On the Mystery of the Letters” Against the Background of the Origenist Controversies of the Fourth and Sixth Centuries,” Historia Religionum, Numero 6, 2014, pp. 45-57.

Jorge Luis Borges and Richard Burgin, Jorge Luis Borges: Conversations, University Press of Mississippi, 1998, p. 244.

I am also reminded of Arthur C. Clarke’s apotheosis in “The Nine Billion Names of God,” a 1953 story in a collection of the same name, 1967, page 9:

“Look,” whispered Chuck, and George lifted his eyes to heaven. (There is always a last time for everything.)

Overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.”)

III

Then Weiss omits to mention an incredible controversy within Kabbalah, which obliges a long excerpt from Gershom Scholem, Origins of the Kabbalah:

“… Several passages suggest that in the current shemittah one of the letters of the Torah is missing. This lack can be understood in two ways. It could signify that one of the letters has a defective form, contrary to its past perfection, that would of course be restored in a future shemittah.

[ … ]

According to this view, one such “defective” or incomplete letter of the alphabet is shin, which in its perfect form should have four heads, but which is written at present with three: ש.

But the statement also could signify that today one of the letters of the alphabet is missing completely: it has become invisible in our aeon but will reappear and become legible once again in the future aeon.

[ … ]

According to another and no less audacious idea, the complete Torah contained in reality seven books, corresponding to the seven sefiroth and shemittoth. It is only in the current shemittah that, through the restrictive power of Stern Judgment, two of these books have shrunk to the point that only a bare hint of their existence remains.

The proof text of this assertion was a passage in the Talmud (Shabbath 116a), according to which the book of Numbers actually consists of three books.

A tradition from the school of Nahmanides specifies that the power inherent in the Torah will manifest itself in the future aeon in such manner that we shall again perceive seven books.

The Book Temunah itself (fol. 31a) avers that the first chapter of Genesis is merely the vestige of a fuller Torah revealed to the shemittah of Grace, but which has become invisible in our shemittah, as the light of this earlier book has disappeared.”

Gershom Scholem, Origins of the Kabbalah, 1962, pp. 471-3.

Hebrew letters lost to history, infernal grammars, Adamic language, antediluvian tablets, lost pronunciations, “secret clues,” missing books of Numbers, all stagger me. Such are my obsessions.

Continuing, Dornseiff explains that στοιχείον had multiple meanings: as a component of a series, the shadow of a sundial, an astronomical unit, a physical element, or, as a letter of the alphabet.

Mystics discern correspondences, but for me, a word with multiple meanings glistens in a woven narrative, echoing messages from the Muse, smoke signals, cosmic semaphore, the whisperings of our forefathers, racial memories from our collective human unconscious.

Jewish and Greek texts differ, Weiss says, because στοιχεΐα does not refer to a certain row or order, as in στοΐχον, but reflects archetypes and elements, or στοιχείων of the created world.

Weiss then introduces Jacques Lacan, whom I had never heard of, highlighting his 20th seminar, “Encore,” (1973), which explains that the letter A, for the “Autre,” or unconscious, was omitted from the incipit of the Bible, which begins with the letter B:

“…la Bible ne commence qu’à la lettre B, elle a laissé la lettre A—pour que je m’en charge.”

Genesis Rabbah 1:10 explains that the first word in the Bible, bereshit (בראש׳ת), begins with the letter B (ב), the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet, rather than with the first letter, A (א).

Now Weiss has me enthralled, and I must adapt the opening sentence of my manuscript to mirror this. He continues with Lacan:

“Why was it created with a beth (ב) … and not with an aleph (א)? Because it connotes cursing (ארךר).

Another interpretation: Why not with an aleph (א), in order not to provide a justification for heretics to plead, “How can the world endure, seeing that it was created with the language of cursing?”

Then Lacan alludes to the ineffable Name, (Hebrew ha-Shem) יהרה and the relation between the Name and the changeable letters that comprise it.

For those who may not know, the pronunciation of yhwh as Yahweh is no more than a guess, as the pronunciation of the secret Name in the tradition of Kabbalah was transmitted orally, whispered with trembling lips, from mouth to ear.

The Tetragrammaton יהרה was never spoken aloud, with the word adonay substituted in its place. The Kabbalists so assiduously obeyed this proscription that the pronunciation died with the last real Kabbalist.

Did that rabbi deem his successors unworthy of the patrimony of their race? In an unspeakable tragedy, the line of oral transmission was interrupted, and the correct pronunciation was lost.

Lacan wrote:

“The name of this God is only The Name, what is called Shem (שם). With regard to the Name that is meant by Shem, I would never have pronounced it during this year’s seminar for reasons which I could have explained to you, although some know its pronunciation.

In fact, regarding pronunciation, there is not only one, we know of many, for example those provided by the Ma’assiot (מעשיךת), and they have varied during the centuries. Moreover the property of this term is rather better pointed at by letters entering the composition of the Name, which are always letters chosen from among the consonants.”

The historical use of consonants in Hebrew is a whole other subject which must be addressed elsewhere. I will note that Gershom Scholem wrote:

“Also related to the magic of language mysticism is the author’s view that the six dimensions of heaven are “sealed” (1:13) by the six permutations of “His great name Yaho” (Hebrew YHW). These three consonants, utilized in Hebrew as matres lectionis for the vowels i, a, and o, which are not written, make up the divine name Yaho, which contains the three consonants of the four-letter name of God, YHWH, as well as the form Yao, which penetrated into the documents of Hellenistic syncretism where its permutations likewise play a role. The signs that were subsequently developed to designate vowels were still unknown to the author.”

Ah, hah. Scholem continues:

“This idea concerning the function of the name Yaho or Yao suggests important parallels. In the system of the Gnostic Valentinus, Iao is the secret name with which the Horos (literally: the limit, the limitation!) frightens away from the world of the pleroma the Sophia-Akhamoth who is in pursuit of Christ.

Does not the cosmos (as distinct from the pleroma), sealed by means of the six permutations of Yao in the Book Yesirah, constitute a sort of monotheistic parallel, perhaps even inspired by polemical intentions, to this Valentinian myth?

In another text of manifestly Jewish-syncretistic character, we similarly find the name Iao, as an invocation that consolidates the world in its limits, a perfect analogy to the sealing in Yesirah: in the cosmogony of the Leiden magical papyrus the earth writhed when the Pythian serpent appeared “and reared up powerfully. But the pole of heaven remained firm, even though it risked being struck by her.”

“Then the god spoke: Iao! And everything was established and a great god appeared, the greatest, who arranged that which was formerly in the world and that which will be, and nothing in the realm of the Height was without order any more.”

This is a long excerpt, but bear with me. Scholem concludes:

“The name Iao appears again among the secret names of this greatest god himself. It is difficult not to suspect a relation here between Jewish conceptions and those of Gnosticism and syncretism.”

Gershom Scholem, Origins of the Kabbalah, 1987, pp. 31-3.

I am not sure that more can be said.

To wrap up, after 1953, Lacan distilled human communication into three registers: the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real.

The Imaginary register is reflective, like a mirror, and therefore confined to the self.

The Symbolic defines and forms a subject, and precedes the Imaginary, though the two are interwoven in actual discourse.

The Real, on the other hand, cannot be expressed. It is left unsaid.

Numerous sources forbid discussion of the secrets of creation, including b. Hagigah 11:2, y. Hagigah 73:3, Genesis Rabbah 1:10 and 8:9, the Memar Marqah, and Philo of Alexandria (Yehuda Liebes, “Maase Bereshit and Maase Merkava as Secret Lore in Philo of Alexandria”).

The Mishnah and the Tosefta prescribe caution when addressing secrets of the Godhead, the secrets of creation, and incest.

In a terse conclusion archetypical of academic literature, Weiss suggests that these forbidden subjects share a “conceptual affinity” to the ineffable Name of the Father, even a Name of the Name.

Estéban Trujillo de Gutiérrez

Smoke Signals: Comments on Borges, Tzahi Weiss, Kabbalah, “On the Matter of Language: The Creation of the World From Letters and Jacques Lacan’s Perception of Letters As Real,” JJTP 17.1, Brill, 2009.

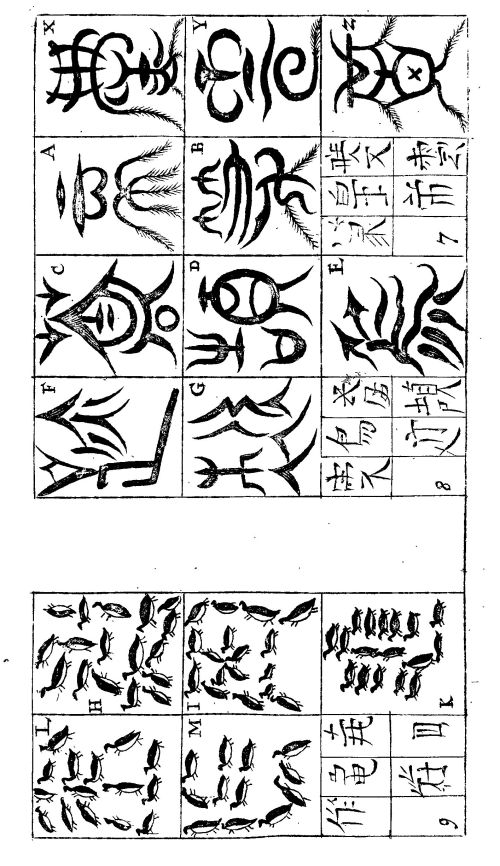

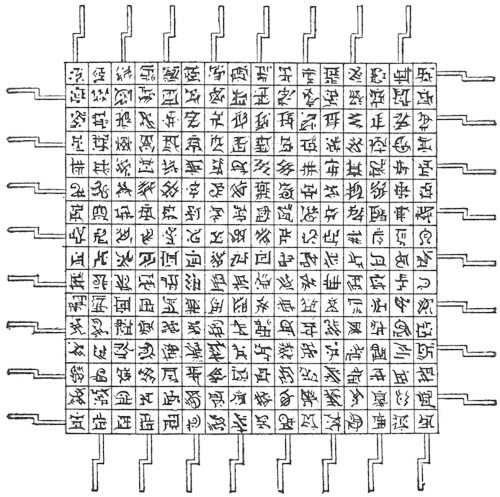

The London Magical Papyrus, British Museum number EA10070,2. On the recto are a series of spells and recipes arranged in 29 columns, including spells for divination, love spells, poisons, and healing. On the verso are “apparently discontinuous memoranda, prescriptions and short invocations.” Column 4 famously features a spell for a revelation, including a recitation in Greek that is intended to be read in the opposite direction as the demotic (4/9-19). The British Museum entry notes that the papyrus was sold in two parts in Thebes, with the first part going to London and the second to Leiden. Griffith and Thompson state that the 3d century CE manuscript is closely connected with the Greek magical papyri from Egypt of the same era, but is heavy in Egyptian mythology. Discovered at Thebes, it was purchased by Anastasi, then Swedish consul at Alexandria. It is believed that it was already torn when he acquired it, as the two halves were later sold separately, with the Leiden MS going to the Dutch government in 1828, and the London MS to the British Museum in 1857, as Number 1072 in Lenormant’s Catalogue. The Leiden half was first introduced to the world in 1830 by C.J.C. Reuvens (Lettres à M. Letronne sur les papyrus bilingues et grecs, Leide, 1830), with a lithograph appearing courtesy of Conrad Leemans in 1839. The London papyrus languished in the British Museum until 1892, when JJ Hess reproduced it in Freiburg. Professor Reuvens focused on the gnostic nature of the MS, which includes names of spirits, gods and demons from Egyptian, Syrian and Jewish traditions, but closer scrutiny revealed that it was not so thoroughly gnostic as initially perceived. The combined MS is consequently termed The Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden, or Pap. mag. LL. London MS: Papyrus Number 10070, formerly Anastasi 1072. Leiden MS: I.383, or Anastasi MSS A.65. © The Trustees of the British Museum. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=933551001&objectId=114184&partId=1#more-views http://www.etana.org/sites/default/files/coretexts/15139.pdf F.LL. Griffith and Herbert Thompson, The Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden, 1904. http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/dmp/

IV

=========Selected Footnotes from the Original=========

“See, for example, Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, trans. James Fentress (London: Fontana Press, 1995), p. 31;

Joseph Dan, On the Sanctity (Hebrew) (Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, 1994), p. 113;

Ithamar Gruenwald, “Letters, Writing, and the Ineffable Name: Magic, Spirituality and Mysticism” (Hebrew), in Massu’ot: Studies in Kabbalistic Literature and Jewish Philosophy in Memory of Prof. Ephraim Gottlieb, ed. Michal Oron and Amos Goldreich ( Jerusalem: Bialik Institute Press, 1994), p. 75.”

I did search for linked versions of these works on the net, and I came up empty. If you have electronic versions, please send them along. I will post them here.

Here is the entire footnote on Wolfson.

“In recent years, Elliot R. Wolfson has made extensive use of Lacan’s concepts in the study of Jewish mysticism, by utilizing, for instance, Lacan’s concept of jouissance and his distinction between the penis as a biological organ and the phallus as a symbolic signifier to explain basic issues in Jewish mysticism.

See, e.g., Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 128–36, 278–79;

Elliot R. Wolfson, Alef, Mem, Tau: Kabbalistic Musings on Time, Truth, and Death (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 135–36;

Elliot R. Wolfson, Through a Speculum That Shines: Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Mysticism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 339–40).

See also Wolfson’s articles on the symbolism of letters:

Elliot R. Wolfson, “Letter Symbolism and Merkavah Imagery in the Zohar,” Alei Shefer: Studies in the Literature of Jewish Thought Presented to Rabbi Dr. Alexandre Safran, ed. Moshe Hallamish (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 1990), 195–236;

Elliot R. Wolfson, “The Anthropomorphic and Symbolic Image of the Letters in the Zohar” (Hebrew), Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought 8 (1989): 147–82.

On the influence of Judaism on Lacan’s thought, see Gerard Haddad, “Judaism in the Life and Work of Jacques Lacan: A Preliminary Study,” trans. Noah Guynn, Yale French Studies 85 (1994): 201–15.

On Lacan’s use of Kabbalistic sources, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being, p. 482 n. 119.”