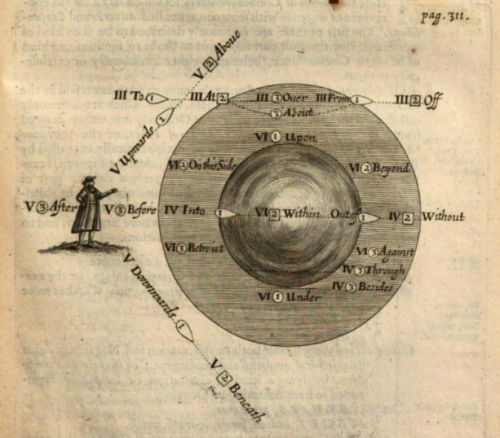

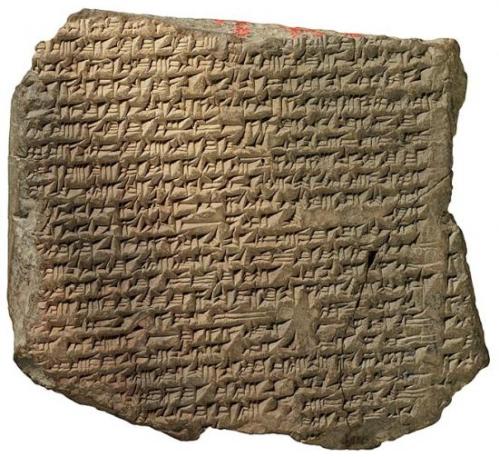

“This idea of a non-hierarchical organization seems, at one point, to have occurred to Wilkins as well. Figure 13.2 reproduces a table found on p. 311 of his Essay. The table describes the workings of prepositions of motion by relating the possible positions (and possible actions) of a human body in a three-dimensional space.

It is a table in which there is no principle of hierarchy whatsoever. Yet this is an isolated example, and Wilkins seems to have lacked the courage to extend this principle to his entire system of content.

Unfortunately, even Lodwick’s primitives for actions were not really primitive at all. It would undoubtedly be possible to identify a series of positions assumed by the human body in space–such as getting up or lying down–and argue that these were intuitively and universally comprehensible; yet the sixteen radicals proposed by Lodwick can be criticized in the same way as Degérando would later do for Wilkins: even such a simple notion as to walk must be defined in terms of movement, the notion of movement requires as its components those of place, of existence in a given place, of a moving substance which in different instants passes from one place to another.

All this presupposes the notions of departure, passage and arrival, as well as that of a principle of action which imparts motion to a substance, and of members which support and convey a body in motion in a specific way (“car glisser, ramper, etc., ne sont pas la même chose que marcher;” “since sliding, climbing, etc., are not the same as walking;” Des signes, IV, 395).

Moreover, it is also necessary to conceive of a terrestrial surface upon which movement was to take place–otherwise one could think of other actions like swimming or flying. However, at this point one should also subject the ideas of surface or members to the same sort of regressive componential analysis.

One solution would be to imagine that such action primitives are selected ad hoc as metalinguistic constructs to serve as parameters for automatic translation. An example of this is the computer language designed by Schank and Abelson (1977), based on action primitives such as PROPEL, MOVER, INGEST, ATRANS OR EXPEL, by which it is possible to analyze more complex actions like to eat (however, when analyzing the sentence “John is eating a frog,” Schank and Abelson–like Lodwick–cannot further analyze frog).

Other contemporary semantic systems do not start by seeking a definition of a buyer in order to arrive eventually at the definition of the action of buying, but start rather by constructing a type-sequence of actions in which a subject A gives money to a subject B and receives an object in exchange.

Clearly the same type-sequence can be employed to define not only the buyer, but also the seller, as well as the notions of to buy, to sell, price, merchandise, and so forth. In the language of artificial intelligence, such a sequence of actions is called a “frame.”

A frame allows a computer to draw inferences from preliminary information: if A is a buyer, then he may perform this and that action; if A performs this or that action, then he may be a buyer; if A obtains merchandise from B but does not pay him, then A is not a guyer, etc., etc.

In still other contemporary semantics, the verb to kill, for example, might be represented as “Xs causes (Xd changes to (- live Xd)) + (animate Xd) & (violent Xs):” if a subject (s) acts, with violent means or instruments, in a way that causes another subject (d), an animate being, to change from a state of living to a state of death, then s has killed d. If we wished, instead, to represent the verb to assassinate, we should add the further specification that d is not only an animate being, but also a political person.

It is worth noting that Wilkins‘ dictionary also includes assassin, glossing it by its synonym murther (erroneously designating it as the fourth species of the third difference in the genera of judicial relations: in fact, it is the fifth species), but limiting the semantic range of the term by “especially, under pretence of Religion.”

It is difficult for a philosophic a priori language to follow the twists and turns of meaning of a natural language.

Properly worked out, Lodwick’s project might represent to assassinate by including a character for to kill and adding to it a note specifying purpose and circumstances.

Lodwick’s language is reminiscent of the one described by Borges in “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” (in Ficciones), which works by agglutinations of radicals representing not substances but rather temporary fluxes. It is a language in which there would be no word for the noun moon but only the verb to moon or to moondle.

Although it is certain that Borges knew, if only at second hand, the work of Wilkins, he probably had never heard of Lodwick. What is certain, however, is that Borges had in mind the Cratylus, 396b–and it is by no means impossible that Lodwick knew this passage as well.

Here Plato, arguing that names are not arbitrary but motivated, gives examples of the way in which, rather than directly representing the things that they designate, words may represent the origin or the result of an action.

For instance, the strange difference (in Greek) between the nominative Zeus and the genitive Dios arose because the original name of Jupiter was a syntagm that expressed the habitual activity associated with the king of the gods: di’hoòn zen, “He through whom life is given.”

Other contemporary authors have tried to avoid the contortions that result from dictionary definitions by specifying the meaning of a term by a set of instructions, that is, a procedure which can decide whether or not a certain word can be applied.

This idea had already appeared in Charles Sanders Pierce (Collected Papers, 2.330): here is provided a long and complex explanation of the term lithium, in which this chemical element was defined not only in relation to its place in the periodic table of elements and by its atomic weight, but also by the operations necessary to produce a specimen of it.

Lodwick never went as far as this; still, his own intuition led him to run counter to an idea that, even in the centuries to follow, proved difficult to overcome. This was the idea that nouns came first; that is, in the process in which language had emerged, terms for things had preceded terms for actions.

Besides, the whole of Aristotelian and Scholastic discussion privileged substances (expressed by common nouns) as the subjects of a statement, in which the terms for actions played the role of predicates.

We saw in chapter 5 that, before the advent of modern linguistics, theorists tended to base their research on nomenclature. Even in the eighteenth century, Vico could still assume that nouns arose before verbs (Scienza nuova seconda, II, 2.4). He found this to be demonstrated not only by the structure of a proposition, but by the fact that children expressed themselves first in names and interjections, and only later in verbs.

Condillac (Essai sur l’origine des connaissances humaines, 82) also affirmed that “for a long time language remained with no words other than nouns.” Stankiewicz (1974) has traced the emergence of a different trend starting with the Hermes of Harris (1751: III), followed by Monboddo (Of the Origins and Progress of Language, 1773-92) and Herder, who, in his Vom Geist der hebräischen Poesie (1787), noted that a noun referred to things as if they were dead while a verb conferred movement upon them, thus stimulating sensation.

Without following Stankiewicz’s reconstruction step by step, it is worth noting that the reevaluation of the role of the verb was assumed in the comparative grammars by the theorists of the Indo-European hypothesis, and that in doing so they followed the old tradition of Sanskrit grammarians, who derived any word from a verbal root (1974: 176).

We can close with the protest of De Sanctis, who, discussing the pretensions of philosophic grammars, criticized the tradition of reducing verbs to nouns and adjectives, observing that: “I love is simply not the same as I am a lover [ . . . ] The authors of philosophical grammars, reducing grammar to logic, have failed to perceive the volitional aspect of thought” (F. De Sanctis, Teoria e storia della litteratura, ed. B. Croce, Bari: Laterza, 1926: 39-40).

In this way, in Lodwick’s dream for a perfect language there appears the first, timid and, at the time, unheeded hint of the problems that were to become the center of successive linguistics.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 264-8.