Eco: Later Critics

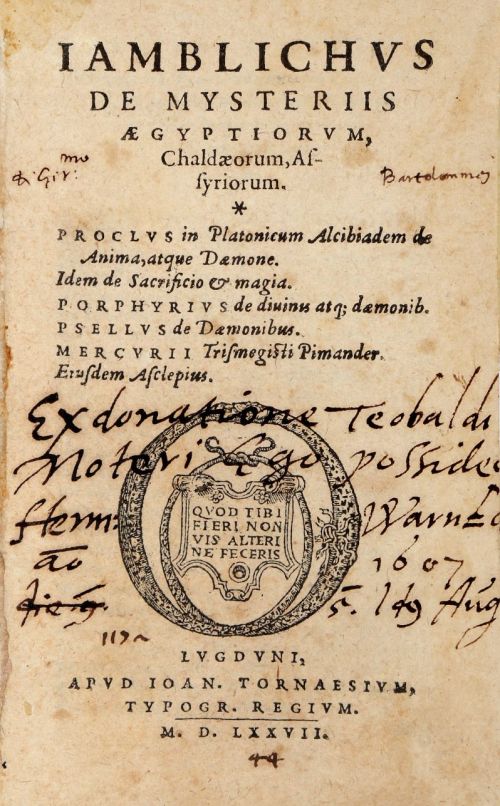

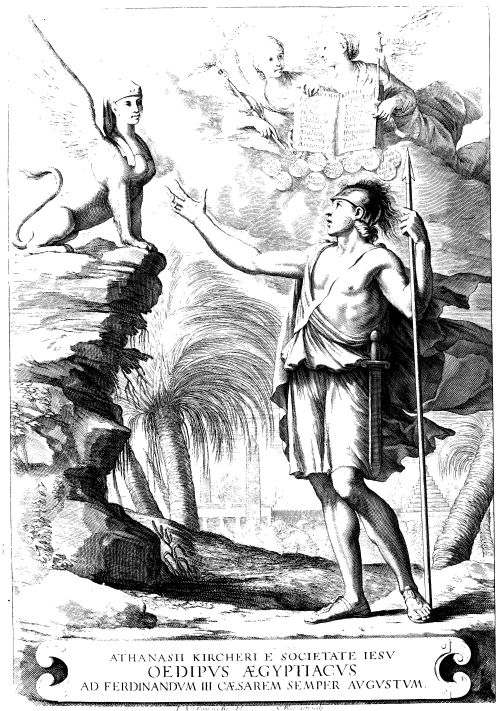

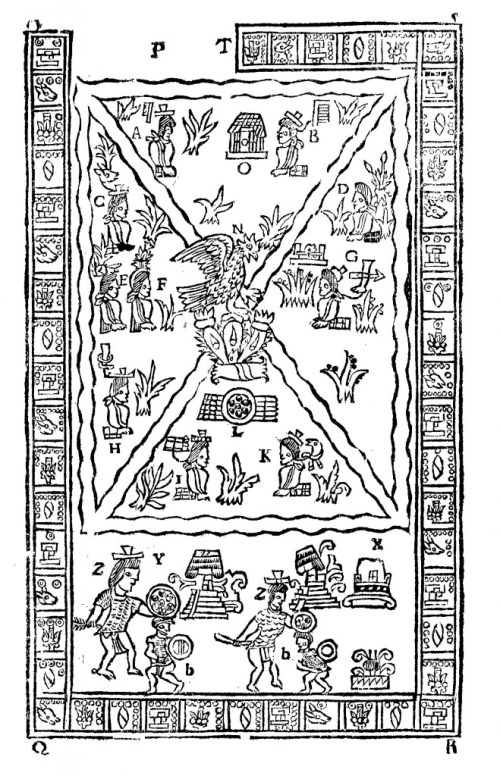

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), Aztec scripture depicting the founding of Mexico City, Oedipus Aegyptiacus, tom. 3, p. 32. A selection of images from works by and related to Athanasius Kircher held in the Special Collections and University Archives of Stanford University Libraries, curated by Michael John Gorman, 2001. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“About a century later, Vico took it for granted that the first language of humanity was in the form of hieroglyphics–that is, of metaphors and animated figures. He saw the pantomime, or acted-out rebus, with which the king of the Scythians replied to Darius the Great as an example of hieroglyphic speech.

He had intimated war with “just five real words;” a frog, a mouse, a bird, a ploughshare, and a bow.

The frog signified that he was born in Scythia, as frogs were born from the earth each summer; the mouse signified that he “like a mouse had made his home where he was born, that is, he had established his nation there;” the bird signified “there the auspices were; that is that he was subject to none but God;” the plough signified that he had made the land his own through cultivation; and finally the bow meant that “as supreme commander in Scythia he had the duty and the might to defend his country.” (Scienza nuova, II, ii, 4, 435).

Despite its antiquity and its primacy as the language of the gods, Vico attributed no quality of perfection to this hieroglyphic language. Neither did he regard it as inherently either ambiguous or secret: “we must here uproot the false opinion held by some of the Egyptians that the hieroglyphs were invented by philosophers to conceal in them their mysteries of lofty esoteric wisdom.

For it was by a common natural necessity that all the first nations spoke in hieroglyphs.” (ibid.).

This “speaking in things” was thus human and natural; its purpose was that of mutual comprehension. It was also a poetic form of speaking that could not, by its very nature, ever be disjoined from either the symbolic language of heroes or the epistolary language of commerce.

This last form of speech “must be understood as having sprung up by their [the plebeians’] free consent, by this eternal property, that vulgar speech and writing are a right of the people” (p. 439).

Thus the language of hieroglyphs, “almost entirely mute, only very slightly inarticulate” (p. 446), once reduced to a mere vestibule of heroic language (made up of images, metaphors, similes and comparisons, that “supplied all the resources of poetic expression,” p. 438) lost its sacred halo of esoteric mystery.

Hieroglyphs would become for Vico the model of perfection for the artistic use of language, without making any claim, however, to replace the ordinary languages of humanity.

Other eighteenth-century critics were moving in the same direction. Nicola Frèret (Reflexions sur les principles généraux de l’art d’écrire, 1718) wrote of hieroglyphic writing as an archaic artifice; Warburton considered it hardly more advanced than the writing systems of the Mexicans (The Divine Legation of Moses, 1737-41).

We have seen what the eighteenth century had to say on the subject of monogeneticism. In this same period, critics were developing a notion of writing as evolving in stages from a pictographic one (representing things), through hieroglyphs (representing qualities and passions as well) to ideograms, capable of giving an abstract and arbitrary representation of ideas.

This, in fact, had been Kircher’s distinction, but now the sequence followed a different order and hieroglyphs were no longer considered as the ordinary language.

In his Essai sur l’origine des langues (1781) Rousseau wrote that “the cruder the writing system, the more ancient the language,” letting it be understood that the opposite held as well: the more ancient the language, the cruder the writing.

Before words and propositions could be represented in conventional characters, it was necessary that the language itself be completely formed, and that the people be governed by common laws.

Alphabetic writing could be invented only by a commercial nation, whose merchants had sailed to distant lands, learning to speak foreign tongues. The invention of the alphabet represented a higher stage because the alphabet did more than represent words, it analyzed them as well.

It is at this point that there begins to emerge the analogy between money and the alphabet: both serve as a universal medium in the process of exchange–of goods in the first instance, of ideas in the second (cf. Derrida 1967: 242; Bora 1989: 40).

This nexus of ideas is repeatedly alluded to by Chevalier de Jaucourt in the entries that he wrote for the Encyclopédie: “Writing,” “Symbol,” “Hieroglyph,” “Egyptian writing,” and “Chinese writing.”

Jaucourt was conscious that if hieroglyphics were entirely in the form of icons, then the knowledge of their meanings would be limited to a small class of priest. The enigmatic character of such a system (in which Kircher took such pride) would eventually force the invention of more accessible forms such as demotic and hieratic.

Jaucourt went further in the attempt to distinguish between different types of hieroglyph. He based his distinctions on rhetoric. Several decades earlier, in fact, in 1730, Du Marsais had published his Traités des trophes, which had tried to delimit and codify all the possible values that a term might take in a process of rhetorical elaboration that included analogies.

Following this suggestion Jaucourt abandoned any further attempt at providing Hermetic explanations, basing himself on rhetorical criteria instead: in a “curiological” hieroglyph, the part stood for the whole; in the “tropical” hieroglyph one thing could be substituted for another on the grounds of similarity.

This limited the scope for interpretive license; once the mechanics of hieroglyphs could be anchored in rhetoric, the possibility for an infinite proliferation of meanings could be reined in.

In the Encyclopédie the hieroglyphs are presented as a mystification perpetrated at the hands of the Egyptian priesthood.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 166-8.