Nebo, God of Wisdom, Scribe of the Gods, Patron of Writing

“The popularity of Nebo was brought about through his association with Merodach. His chief seat of worship was at Borsippa, opposite to Babylon, and when the latter city became the seat of the imperial power the proximity of Borsippa greatly assisted the cult of Nebo.

So close did the association between the deities of the two cities become that at length Nebo was regarded as the son of Merodach—a relationship that often implies that the so-called descendant of the elder god is a serious rival, or that his cult is nearly allied to the elder worship.

Nebo had acquired something of a reputation as a god of wisdom, and probably this it was which permitted him to stand separately from Merodach without becoming absorbed in the cult of the great deity of Babylon.

Nabu, or Nebo, sculpted bronze figure by Lee Lawrie. Door detail, east entrance, Library of Congress John Adams Building, Washington, D.C.

Photographed 2007 by Carol Highsmith (1946–), who explicitly placed the photograph in the public domain. – Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nabu#/media/File:Nabu-Lawrie-Highsmith.jpeg

He was credited, like Ea, with the invention of writing, the province of all ‘wise’ gods, and he presided over that department of knowledge which interpreted the movements of the heavenly bodies. The priests of Nebo were famous as astrologers, and with the bookish king Assur-bani-pal, Nebo and his consort Tashmit were especial favourites as the patrons of writing.

By the time that the worship of Merodach had become recognised at Babylon, the cult of Nebo at Borsippa was so securely rooted that even the proximity of the greatest god in the land failed to shake it.

Even after the Persian conquest the temple-school at Borsippa continued to flourish.

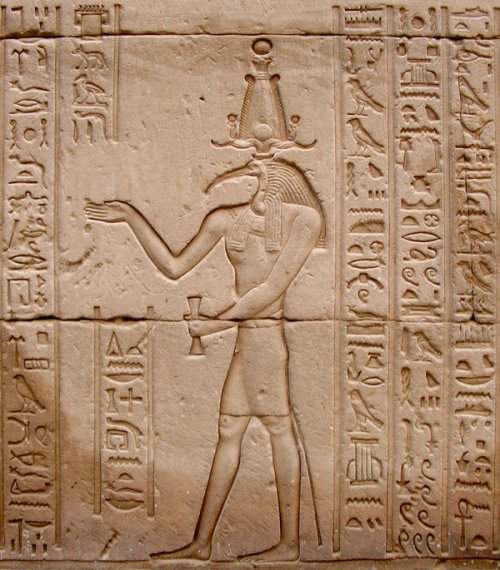

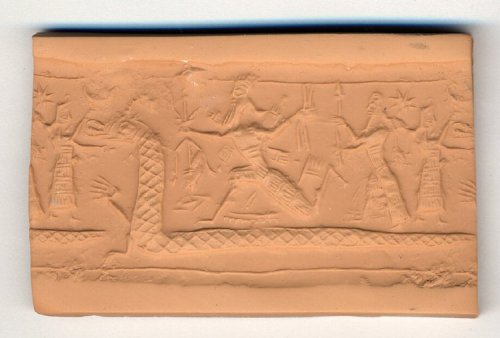

But although Nebo thus ‘outlived’ many of the greater gods it is now almost impossible to trace his original significance as a deity. Whether solar or aqueous in his nature—and the latter appears more likely— he was during the period of Merodach’s ascendancy regarded as scribe of the gods, much as Thoth was the amanuensis of the Egyptian otherworld—that is to say, he wrote at the dictation of the higher deities.

When the gods were assembled in the Chamber of Fates in Merodach’s temple at Babylon, he chronicled their speeches and deliberations and put them on record. Indeed he himself had a shrine in this temple of E-Sagila, or ‘the lofty house,’ which was known as E-Zila, or ‘the firm house.’

Once during the New Year festival Nebo was carried from Borsippa to Babylon to his father’s temple, and in compliment was escorted by Merodach part of the way back to his own shrine in the lesser city. It is strange to see how closely the cults of the two gods were interwoven.

The Kings of Babylonia constantly invoke them together, their names and those of their temples are found in close proximity at every turn, and the symbols of the bow and the stylus or pen, respectively typical of the father and the son, are usually discovered in one and the same inscription.

Even Merodach’s dragon, the symbol of his victory over the dark forces of chaos, is assigned to Nebo.”

Lewis Spence, Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria, 1917, pp. 184-6.

begins with a description of the Creation and then goes on to describe a Flood, and there is little doubt that certain passages in this text are the originals of the Babylonian version as given in the Seven Tablets.

begins with a description of the Creation and then goes on to describe a Flood, and there is little doubt that certain passages in this text are the originals of the Babylonian version as given in the Seven Tablets. .

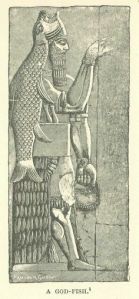

. , Ilu Nagar Ilu Nagar, i.e., “the workmen gods,” about whom nothing is known.

, Ilu Nagar Ilu Nagar, i.e., “the workmen gods,” about whom nothing is known.