From a papyrus of the Ptolemaic period we obtain some interesting facts about the great skill in working magic and about the knowledge of magical formulæ which were possessed by a prince called Setnau Khâ-em-Uast.

He knew how to use the powers of amulets and talismans, and how to compose magical formulæ, and he was master both of religious literature and of that of the “double house of life,” or library of magical books.

One day as he was talking of such things one of the king’s wise men laughed at his remarks, and in answer Setnau said, “If thou wouldst read a book possessed of magical powers come with me. and I will show it to thee, the book was written by Thoth himself, and in it there are two formulæ. The recital of the first will enchant (or bewitch) heaven, earth, hell, sea, and mountains, and by it thou shalt see all the birds, reptiles, and fish, for its power will bring the fish to the top of the water. The recital of the second will enable a man if he be in the tomb to take the form which he had upon earth,” etc.

When questioned as to where the book was, Setnau said that it was in the tomb of Ptah-nefer-ka at Memphis. A little later Setnau went there with his brother and passed three days and three nights in seeking for the tomb of Ptah-nefer-ka, and on the third day they found it; Setnau recited some words over it, and the earth opened and they went down to the place where the book was.

When the two brothers came into the tomb they found it to be brilliantly lit up by the light which came forth from the book; and when they looked they saw not only Ptah-nefer-ka, but his wife Ahura, and Merhu their son.

Now Ahura and Merhu were buried at Coptos but their doubles had come to live with Ptah- nefer-ka by means of the magical power of Thoth.

Setnau told them that he had come to take away the book, but Ahura begged him not to do so, and related to him the misfortunes which had already followed the possession of it.

She was, it seems, the sister of Ptah-nefer-ka whom she married, and after the birth of her son Merhu, her husband seemed to devote himself exclusively to the study of magical books, and one day a priest of Ptah promised to tell him where the magical book described above might be found if he would give him a hundred pieces of silver, and provide him with two handsome coffins.

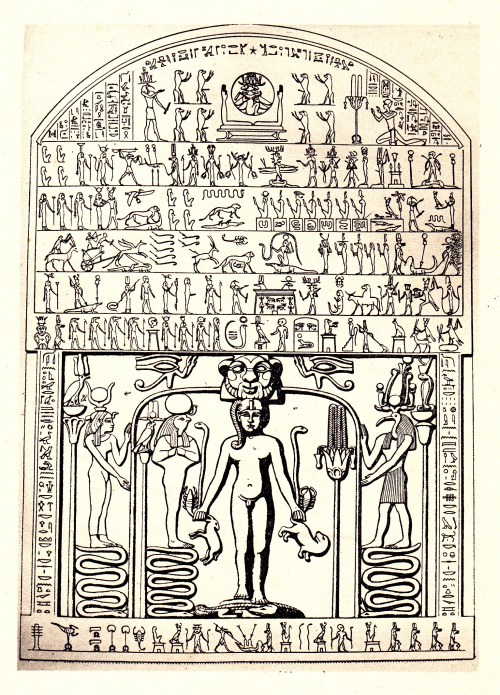

When the money and the coffins had been given to him, the priest of Ptah told Ptah-nefer-ka that the book was in an iron box in the middle of the river at Coptos.

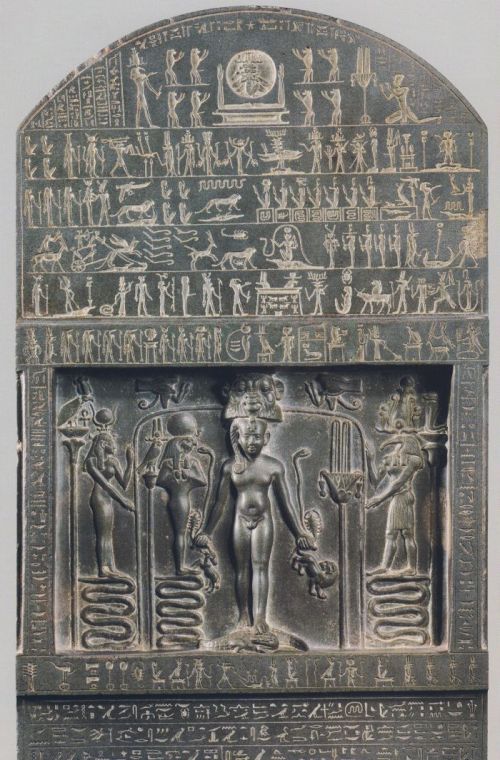

“The iron box is in a bronze box, the bronze box is in a box of palm-tree wood, the palm tree wood box is in a box of ebony and ivory, the ebony and ivory box is in a silver box, the silver box is in a gold box, and in the gold (sic) box lies the book.

The box wherein is the book is surrounded by swarms of serpents and scorpions and reptiles of all kinds, and round it is coiled a serpent which cannot die.”

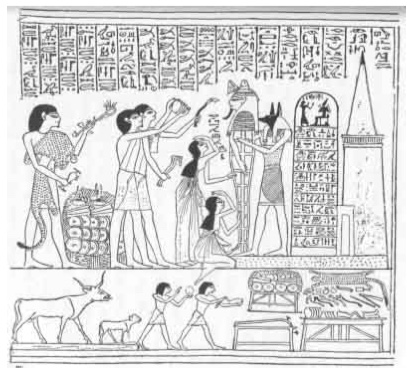

Ptah-nefer-ka told his wife and the king what he had heard, and at length set out for Coptos with Ahura and Merhu in the royal barge; having arrived at Coptos he went to the temple of Isis and Harpocrates and offered up a sacrifice and poured out a libation to these gods.

Five days later the high priest of Coptos made for him the model of a floating stage and figures of workmen provided with tools; he then recited words of power over them and they became living, breathing men, and the search for the box began.

Having worked for three days and three nights they came to the place where the box was. Ptah-nefer-ka dispersed the serpents and scorpions which were round about the nest of boxes by his words of power, and twice succeeded in killing the serpent coiled round the box, but it came to life again; the third time he cut it into two pieces, and laid sand between them, and this time it did not take its old form again.

He then opened the boxes one after the other, and taking out the gold box with the book inside it carried it to the royal barge. He next read one of the two formula in it and so enchanted or bewitched the heavens and the earth that he learned all their secrets; he read the second and he saw the sun rising in the heavens with his company of the gods, etc.

His wife Ahura then read the book and saw all that her husband had seen. Ptah-nefer-ka then copied the writings on a piece of new papyrus, and having covered the papyrus with incense dissolved it in water and drank it; thus he acquired the knowledge which was in the magical book.

Meanwhile these acts had stirred the god Thoth to wrath, and he told Râ what Ptah-nefer-ka had done. As a result the decree went forth that Ptah-nefer-ka and his wife and child should never return to Memphis, and on the way back to Coptos Ahura and Merhu fell into the river and were drowned; and while returning to Memphis with the book Ptah-nefer-ka himself was drowned also.

Setnau, however, refused to be diverted from his purpose, and he insisted on having the book which he saw in the possession of Ptah-nefer-ka; the latter then proposed to play a game of draughts and to let the winner have the book.

The game was for fifty-two points, and although Ptah-nefer-ka tried to cheat Setnau, he lost the game. At this juncture Setnau sent his brother Anhaherurau up to the earth to bring him his talismans of Ptah and his other magical writings, and when he returned he laid them upon Setnau, who straightway flew up to heaven grasping the wonderful book in his hand.

As he went up from the tomb light went before him, and the darkness closed in behind him; but Ptah-nefer-ka said to his wife, “I will make him bring back this book soon, with a knife and a rod in his hand and a vessel of fire upon his head.”

Of the bewitchment of Setnau by a beautiful woman called Tabubu and of his troubles in consequence thereof we need make no mention here: it is sufficient to say that the king ordered him to take the book back to its place, and that the prophecy of Ptah-nefer-ka was fulfilled. (For translations see Brugsch, Le Roman de Setnau (in Revue Archéologique, 2nd series, Vol. xvi., 1867, p. 161 ff.); Maspero, Contes Égyptiens, Paris, 1882, pp. 45-82; Records of the Past, vol. iv., pp. 129-148; and for the original Demotic text see Mariette, Les Papyrus du Musée de Boulaq, tom. i., 1871, pll. 29-32; Revillout, Le Roman de Setna, Paris, 1877; Hess, Roman von Sfne Ha-m-us. Leipzig, 1888).

E.A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, London, 1901. Pp. 142-6.