The Genesis of the Kings List

“The single fact which has shaken it to its very foundations is the discovery of the date to which the reign of Sargon of Accad must be assigned. The last king of of Babylonia, Nabonidos, had antiquarian tastes, and busied himself not only with the restoration of the old temples of his country, but also with the disinterment of the memorial cylinders which their builders and restorers had buried beneath their foundations.

It was known that the great temple of the Sun-god at Sippara, where the mounds of Abu-Habba now mark its remains, had been originally erected by Naram-Sin the son of Sargon, and attempts had been already made to find the records which, it was assumed, he had entombed under its angles. With true antiquarian zeal, Nabonidos continued the search, and did not desist until, like the Dean and Chapter of some modern cathedral, he had lighted upon “the foundation-stone” of Naram-Sin himself.

This “foundation-stone,” he tells us, had been seen by none of his predecessors for 3200 years. In the opinion, accordingly, of Nabonidos, a king who was curious about the past history of his country, and whose royal position gave him the best possible opportunities for learning all that could be known about it, Naram-Sin and his father Sargon I, lived 3200 years before his own time, or 3750 B.C.

The date is so remote and so contrary to all our preconceived ideas regarding the antiquity of the Babylonian monarchy, that I may be excused if at first I expressed doubts as to its accuracy. We are now accustomed to contemplate with equanimity the long chronology which the monuments demand for the history of Pharaonic Egypt, but we had also been accustomed to regard the history of Babylonia as beginning at the earliest in the third millennium before our era. Assyrian scholars had inherited the chronological prejudices of a former generation, and a starveling chronology seemed to be confirmed by the statements of Greek writers.

I was, however, soon forced to re-consider the reasons of my scepticism. The cylinder on which Nabonidos accounts his discovery of the foundation-stone of Naram-Sin was brought from the excavations of Mr. Hormuzd Rassam in Babylonia, and explained by Mr. Pinches six years ago.

Soon afterwards, Mr. Pinches was fortunate enough to find among some other inscriptions from Babylonia fragments of three different lists, in one of which the kings of Babylonia were arranged in dynasties, and the number of years each king reigned was stated, as well as the number of years the several dynasties lasted.

An Assyrian copy of a similar list had been already discovered by Mr. George Smith, who, with his usual quickness of perception, saw that it must have resembled the lists from which Berossos, the Greek historian of Chaldaea, drew the materials of his chronology; but the copy was so mere a fragment that the chronological position of the kings mentioned upon it was a matter of dispute.

Happily this is not the case with the principal test published by Mr. Pinches. It had been compiled by a native of Babylon, who consequently began with the first dynasty which made Babylon the capital of the kingdom, and who seems to have flourished in the time of Nabonidos. We can check the accuracy of his statements in a somewhat curious way.

One of the two other texts brought to light by Mr. Pinches is a schoolboy’s exercise copy of the first two dynasties mentioned on the annalistic tablet. There are certain variations between thc two texts, however, which show that the schoolboy or his master must have used some other list of the early kings than that which was employed by the compiler of the tablet; nevertheless, the names and the regnal years, with one exception, agree exactly in each.

In Assyria, an accurate chronology was kept by means of certain officers, the so-called Eponyms, who were changed every year and gave their names to the year over which they presided. We have at present no positive proof that the years were dated in the same way in Babylonia; but since most Assyrian institutions were of Babylonian origin, it is probable that they were.

At all events, the scribes of a later day believed that they had trustworthy chronological evidence extending back into a dim antiquity; and when we remember the imperishable character of the clay literature of the country, and the fact that the British Museum actually contains deeds and other legal documents dated in the rein of Khammuragas, more than four thousand years ago, there is no reason why we should not consider the belief to have been justified.”

A.H. Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians, 5th ed., London, 1898, pp. 21-3.

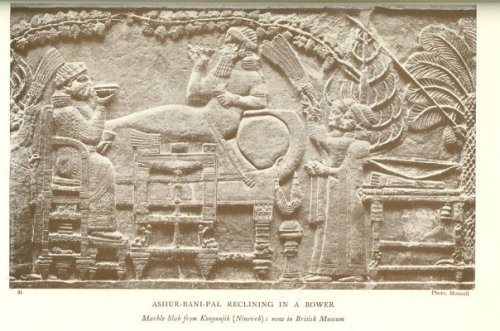

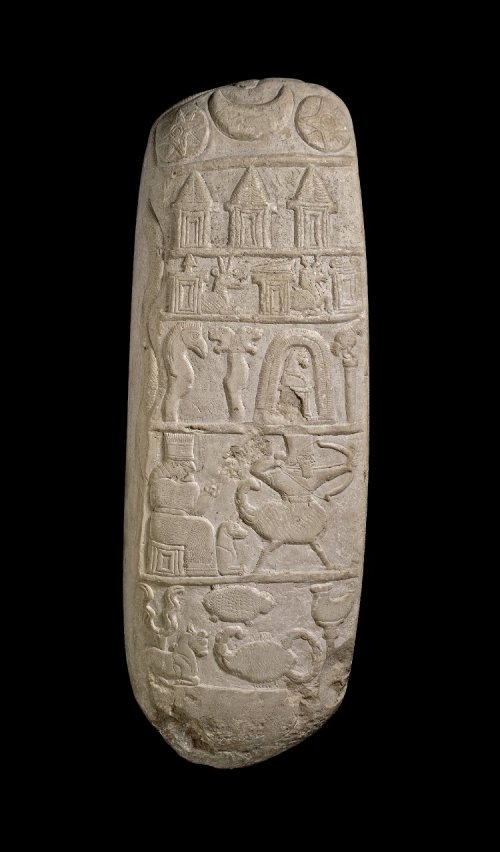

![Illustration: Tablet sculptured with a scene representing the worship of the Sun-god in the Temple of Sippar. The Sun-god is seated on a throne within a pavilion holding in one hand a disk and bar which may symbolize eternity. Above his head are the three symbols of the Moon, the Sun, and the planet Venus. On a stand in front of the pavilion rests the disk of the Sun, which is held in position by ropes grasped in the hands of two divine beings who are supported by the roof of the pavilion. The pavilion of the Sun-god stands on the Celestial Ocean, and the four small disks indicate either the four cardinal points or the tops of the pillars of the heavens. The three figures in front of the disk represent the high priest of Shamash, the king (Nabu-aplu-iddina, about 870 B.C.) and an attendant goddess. [No. 91,000.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00582752_001_l.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration: Tablet inscribed with a list of the Signs of the Zodiac. [No. 77,821.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/015.png?w=500)

![Illustration: Shamash the Sun-god setting (?) on the horizon. In his right he holds a tree (?), and in his left a ... with a serrated edge. Above the horizon is a goddess who holds in her left hand an ear of corn. On the right is a god who seems to be setting free a bird from his right hand. Round him is a river with fish in it, and behind him is an attendant god; under his foot is a young bull. To the right of the goddess stand a hunting god, with a bow and lasso, and a lion. From the seal-cylinder of Adda ..., in the British Museum. About 2500 B.C. [No. 89,115.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00135126_001_l.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration: Shamash the Sun-god rising on the horizon, flames of fire ascending from his shoulder. The two portals of the dawn, each surmounted by a lion, are being drawn open by attendant gods. From a Babylonian seal cylinder in the British Museum. [No. 89,110.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00323246_001_l.jpg?w=500)