Timeline: Sumer

5400 BCE: The City of Eridu is founded.

5000 BCE: Godin Tepe settled.

5000 BCE – 1750 BCE: Sumerian civilization in the Tigris-Euphrates valley.

5000 BCE: Sumer inhabited by Ubaid people.

5000 BCE – 4100 BCE: The Ubaid Period in Sumer.

5000 BCE: Evidence of burial in Sumer.

4500 BCE: The Sumerians built their first temple.

4500 BCE: The City of Uruk founded.

4100 BCE – 2900 BCE: Uruk Period in Sumer.

3600 BCE: Invention of writing in Sumer at Uruk.

3500 BCE: Late Uruk Period.

3500 BCE: First written evidence of religion in Sumerian cuneiform.

2900 BCE – 2334 BCE: The Early Dynastic Period in Sumer.

2900 BCE – 2300 BCE: Early Dynastic I.

2750 BCE – 2600 BCE: Early Dynastic II.

2600 BCE -2300 BCE: Early Dynastic III. (Fara Period).

2600 BCE – 2000 BCE: The Royal Graves of Ur used in Sumer.

2500 BCE: First Dynasty of Lagash under King Eannutum is the first empire in Mesopotamia.

2330 BCE -2190 BCE: Akkadian Period.

2350 BCE: First code of laws by Urukagina, king of Lagash.

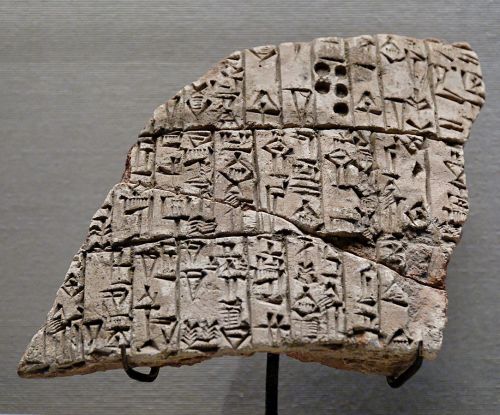

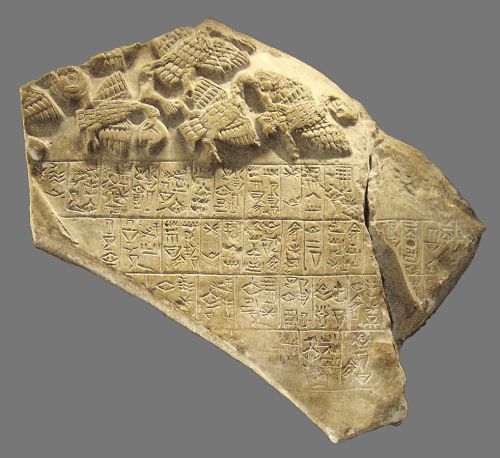

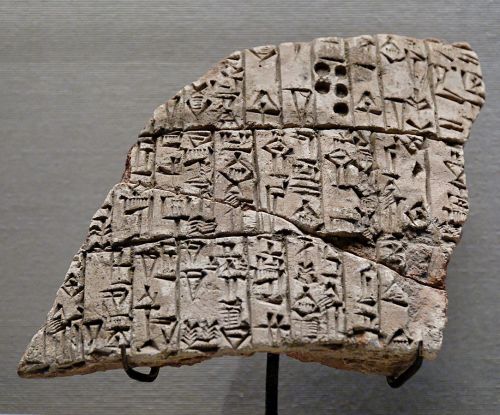

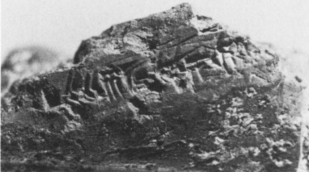

Fragment of an inscription of Urukagina; it reads as follows: “He [Uruinimgina] dug (…) the canal to the town-of-NINA. At its beginning, he built the Eninnu; at its ending, he built the Esiraran.” (Musée du Louvre)

Public Domain

Clay cone Urukagina Louvre AO4598ab.jpg

Uploaded by Jastrow

Created: circa 2350 BC

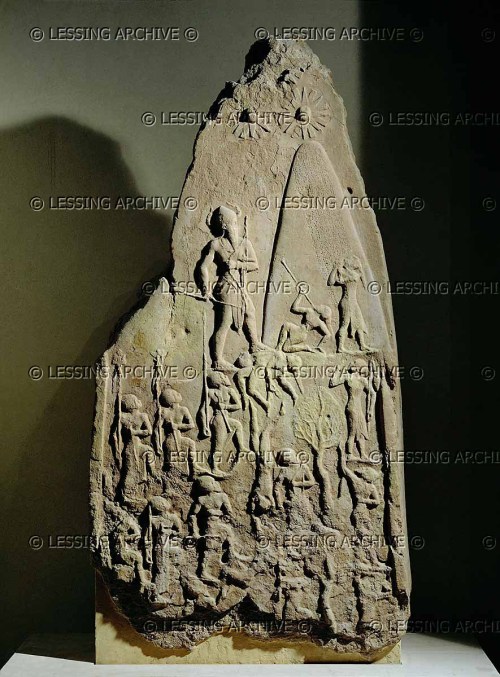

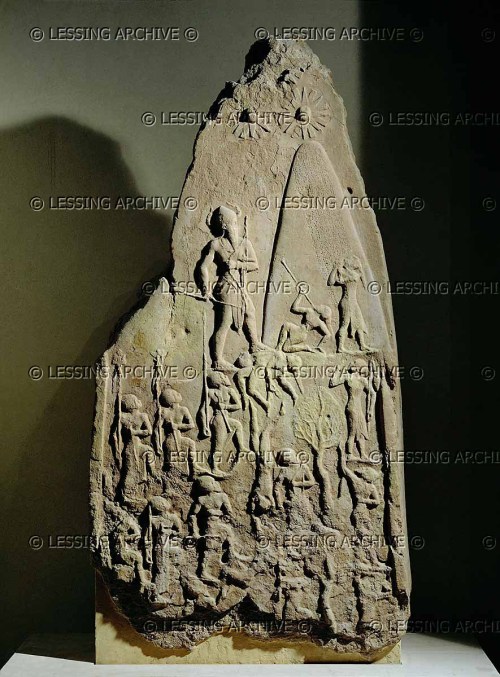

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin.

The original Akkadian states that the six foot tall stele commemorates the victory of King Naram-Sin of Akkad over King Satuni, ruler of the Lullubi people of the mountainous Zagros. Naram-Sin was the grandson of Sargon, founder of the Akkadian empire, and the first potentate to unite the entirety of Mesopotamia in the late 24th century BCE.

Naram-Sin was the fourth sovereign of his line, following his uncle Rimush and his father Manishtusu. The Sumerian King List ascribes his rule of 36 years to 2254 BCE to 2218 BCE, a long reign not otherwise confirmed by extant documents.

The stele depicts the Akkadian army climbing the Zagros Mountains, eradicating all resistance. The slain are trampled underfoot or thrown from a precipice. Naram-Sin is portrayed wearing the horned crown of divinity, symbolic of a ruler who aspires to divinity himself. In official documentation, the name of Naram-Sin was preceded by the divine determinative. He styled himself the King of the Four Regions, or King of the World.

The stele was removed from Sippar to Susa, Iran a thousand years later by the Elamite King Shutruk-Nahhunte, as a war prize after his victorious campaign against Babylon in the 12th century BCE.

Alongside the preexisting cuneiform inscription, King Shutruk-Nahhunte appended another one glorifying himself, recording that the stele was looted during the pillage of Sippar.

Jacques de Morgan, Mémoires, I, Paris, 1900, p. 106, 144 sq, pl. X.

Victor Scheil, Mémoires, II, Paris, 1900, p. 53 sq, pl. II.

Victor Scheil, Mémoires, III, Paris, 1901, p. 40 sq, pl. II.

André Parrot, Sumer, Paris, 1960, fig. 212-213.

Pierre Amiet, L’Art d’Agadé au musée du Louvre, Paris, Ed. de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1976 – p. 29-32.

Louvre Museum

Accession number Sb 4

Found by J. de Morgan

Photo: Rama

This work is free software; you can redistribute it or modify it under the terms of the CeCILL. The terms of the CeCILL license are available at http://www.cecill.info.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Victory_stele_of_Naram_Sin_9068.jpg

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/victory-stele-naram-sin

2218 BCE – 2047 BCE: The Gutian Period in Sumer.

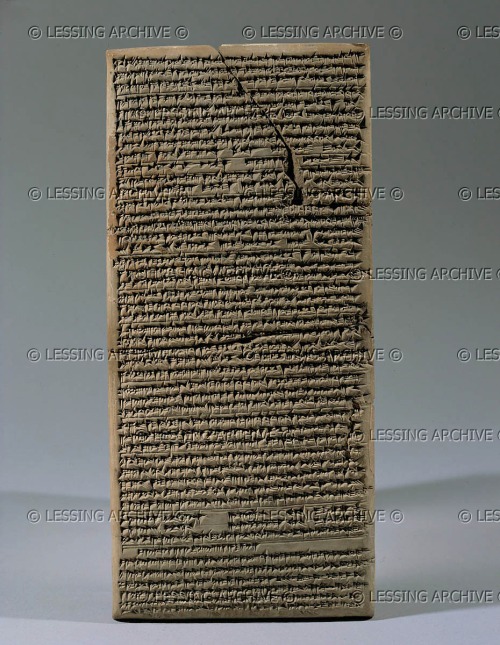

2150 BCE – 1400 BCE: The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh written on clay tablets.

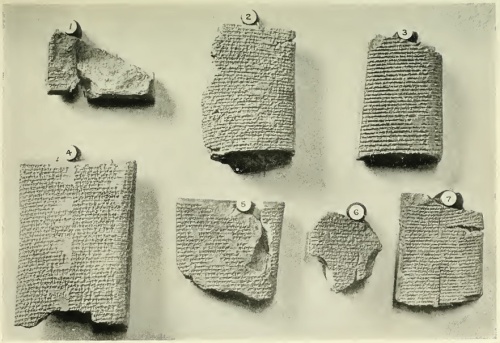

Library of Ashurbanipal / The Flood Tablet / The Gilgamesh Tablet

Date 15 July 2010

Current location: British Museum wikidata:Q6373

Source/Photographer Fæ (Own work)

Other versions File:British Museum Flood Tablet 1.jpg

British Museum reference K.3375

Detailed description:

Part of a clay tablet, upper right corner, 2 columns of inscription on either side, 49 and 51 lines + 45 and 49 lines, Neo-Assyrian., Epic of Gilgamesh, tablet 11, story of the Flood. ~ Description extract from BM record.

Location Room 55

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Library_of_Ashurbanipal_The_Flood_Tablet.jpg

2100 BCE: The Reign of Utu-Hegal at Uruk in Sumer and creation of the Sumerian King List.

2095 BCE – 2047 BCE: King Shulgi reigns in Ur, (following Gane).

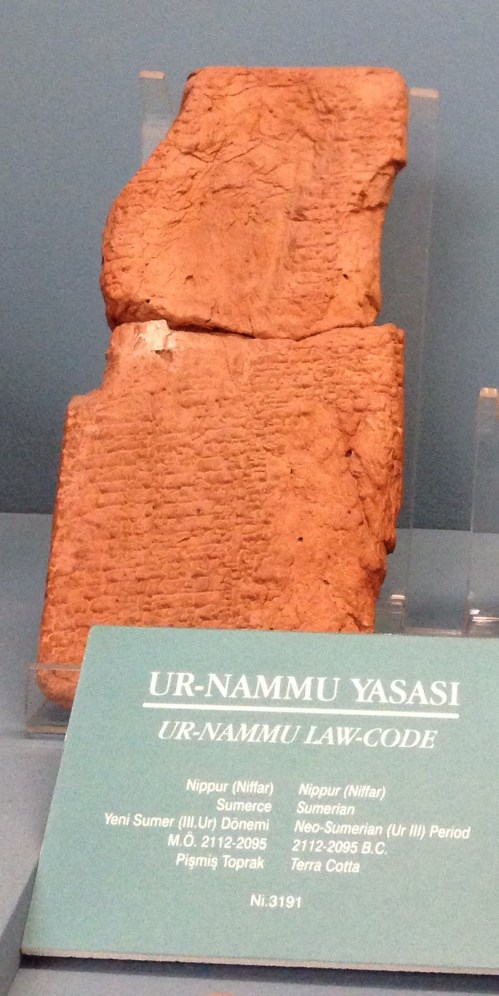

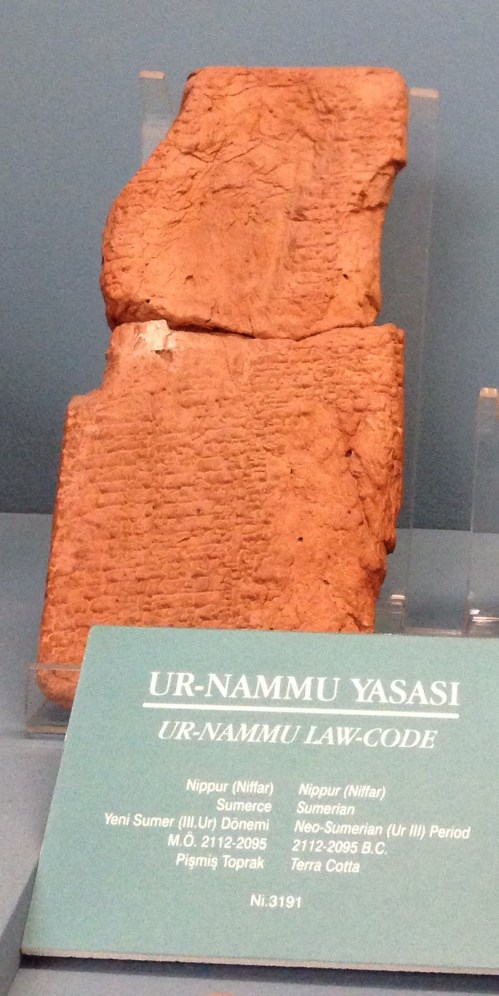

2047 BCE – 2030 BCE: Ur-Nammu’s reign over Sumer. The legal Code of Ur-Nammu dates to 2100 BCE – 2050 BCE.

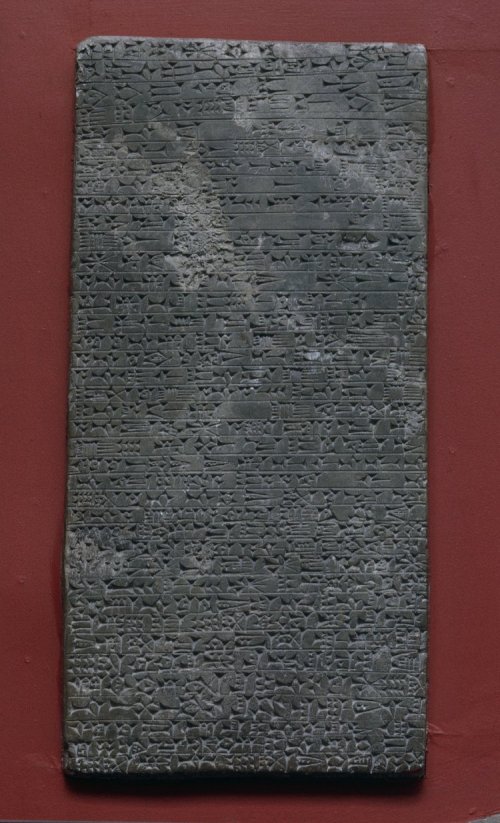

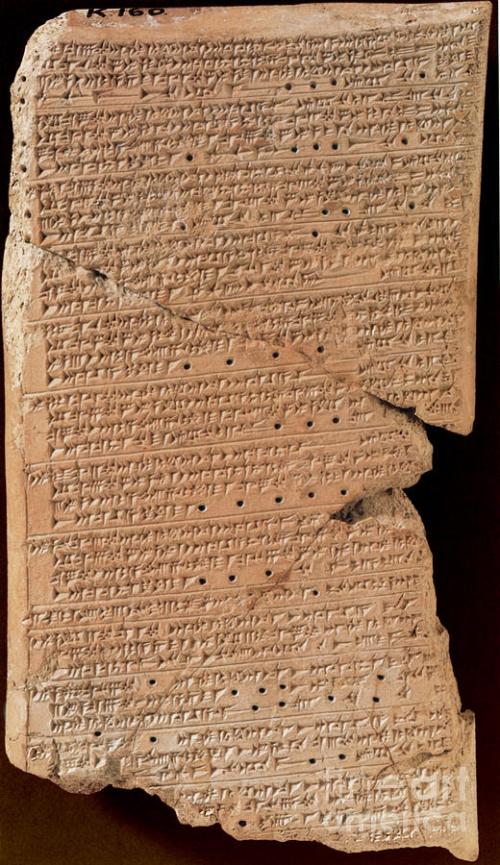

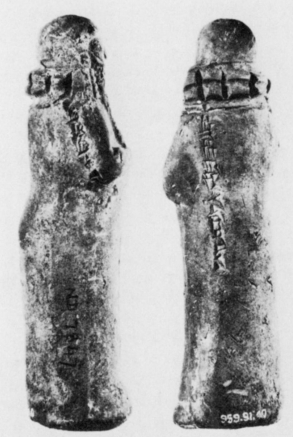

“In all probability I would have missed the Ur-Nammu tablet altogether had it not been for an opportune letter from F. R. Kraus, now Professor of Cuneiform Studies at the University of Leiden in Holland…

His letter said that some years ago, in the course of his duties as curator in the Istanbul Museum, he had come upon two fragments of a tablet inscribed with Sumerian laws, had made a “join” of the two pieces, and had catalogued the resulting tablet as No. 3191 of the Nippur collection of the Museum…

Since Sumerian law tablets are extremely rare, I had No. 3191 brought to my working table at once. There it lay, a sun-baked tablet, light brown in color, 20 by 10 centimeters in size. More than half of the writing was destroyed, and what was preserved seemed at first hopelessly unintelligible. But after several days of concentrated study, its contents began to become clear and take shape, and I realized with no little excitement that what I held in my hand was a copy of the oldest law code as yet known to man.”

Samuel Noah Kramer, History Begins at Sumer, pp. 52–55.

CC0

File:Ur Nammu code Istanbul.jpg

Uploaded by Oncenawhile

Created: 1 August 2014

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Ur-Nammu#/media/File:Ur_Nammu_code_Istanbul.jpg

2047 BCE – 1750 BCE: The Ur III Period in Sumer, known as the Sumerian Renaissance, or the Neo-Sumerian Empire.

2038 BCE: King Shulgi of Ur builds his great wall in Sumer.

2000 BCE – 1600 BCE: Old Babylonian Period.

2000 BCE – 1800 BCE: Isin – Larsa.

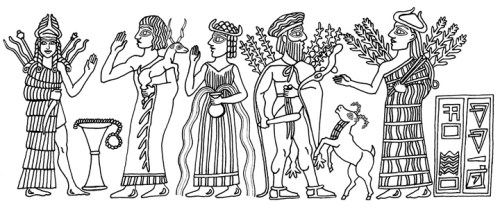

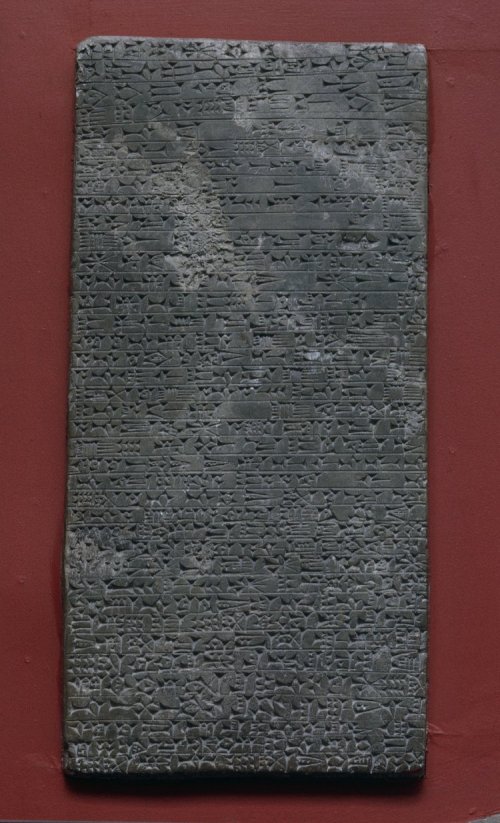

Text:

“IN ERIDU: ALULIM RULED AS KING 28,800 YEARS. ELALGAR RULED 43,200 YEARS. ERIDU WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO BAD-TIBIRA. AMMILU’ANNA THE KING RULED 36,000 YEARS. ENMEGALANNA RULED 28,800 YEARS. DUMUZI RULED 28,800 YEARS. BAD-TIBIRA WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO LARAK. EN-SIPA-ZI-ANNA RULED 13,800 YEARS. LARAK WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO SIPPAR. MEDURANKI RULED 7,200 YEARS. SIPPAR WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO SHURUPPAK. UBUR-TUTU RULED 36,000 YEARS. TOTAL: 8 KINGS, THEIR YEARS: 222,600”

MS in Sumerian on clay, probably Larsa Babylonia, 2000-1800 BC, 1 tablet, 8,1×6,5×2,7 cm, single column, 26 lines in cuneiform script.

5 other copies of the Antediluvian king list are known only: MS 3175, 2 in Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, one is similar to this list, containing 10 kings and 6 cities, the other is a big clay cylinder of the Sumerian King List, on which the kings before the flood form the first section, and has the same 8 kings in the same 5 cities as the present.

A 4th copy is in Berkeley: Museum of the University of California, and is a school tablet. A 5th tablet, a small fragment, is in Istanbul.

The list provides the beginnings of Sumerian and the world’s history as the Sumerians knew it. The cities listed were all very old sites, and the names of the kings are names of old types within Sumerian name-giving. Thus it is possible that correct traditions are contained, though the sequence given need not be correct. The city dynasties may have overlapped.

It is generally held that the Antediluvian king list is reflected in Genesis 5, which lists the 10 patriarchs from Adam to Noah, all living from 365 years (Enoch) to 969 years (Methuselah), altogether 8,575 years.

It is possible that the 222,600 years of the king list reflects a more realistic understanding of the huge span of time from Creation to the Flood, and the lengths of the dynasties involved.

The first of the 5 cities mentioned, Eridu, is in Uruk, in the area where the myths place the Garden of Eden, while the last city, Shuruppak, is the city of Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah.

Jöran Friberg: A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts. Springer 2007.

Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences.

Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection, vol. 6, Cuneiform Texts I. pp. 237-241. Andrew George, ed.: Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection, Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology, vol. 17,

Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection, Cuneiform texts VI. CDL Press, Bethesda, MD, 2011, text 96, pp. 199-200, pls. LXXVIII-LXXIX.

Andrew E. Hill & John H. Walton: A Survey of the Old Testament, 3rd ed., Grand Rapids, MI., Zondervan Publishing House, 2009, p. 206.

Zondervan Illustrated Bible, Backgrounds, Commentary. John H. Walton, gen. ed. Grand Rapids, Mich., Zondervan, 2009, vol 1, p. 482, vol. 5, p. 398.

1861 BCE – 1837 BCE: King Enlil-bāni reigns in Isin.

1792 BCE – 1750: Reign of King Hammurabi (Old Babylonian Period).

1772 BCE: The Code of Hammurabi: One of the earliest codes of law in the world.

The Code of Hammurabi was discovered by archaeologists in 1901, with its editio princeps translation published in 1902 by Jean-Vincent Scheil. This nearly complete example of the Code is carved into a diorite stele in the shape of a huge index finger, 2.25-metre (7.4 ft) tall. The Code is inscribed in Akkadian, using cuneiform script. It is currently on display in the Louvre, with exact replicas in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, the library of the Theological University of the Reformed Churches (Dutch: Theologische Universiteit Kampen voor de Gereformeerde Kerken) in The Netherlands, the Pergamon Museum of Berlin and the National Museum of Iran in Tehran.

CC BY-SA 2.0 fr

File:Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg

Uploaded by Rama

Uploaded: 8 November 2005

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Hammurabi#/media/File:Code-de-Hammurabi-1.jpg

1750 BCE: Elamite invasion and Amorite migration ends the Sumerian civilization.

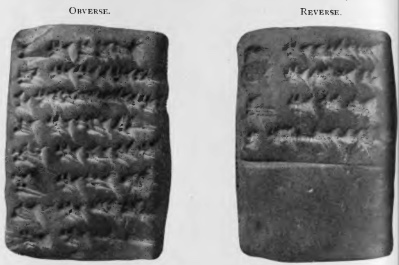

Cuneiform tablet with the Sumerian tale of The Deluge, dated to circa 1740 BCE, from the ruins of Nippur.

From the permanent collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Text and photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. All rights reserved.

1600 BCE – 1155 BCE: Kassite Period.

1595 BCE: King Agum-kakrime, aka Agum II, Kassite Kingdom.

1350 BCE – 1050 BCE: Middle Assyrian Period.

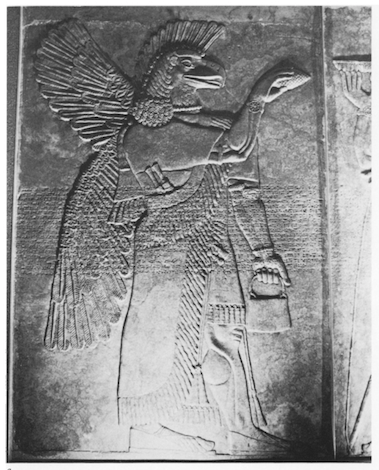

A gypsum memorial slab from the Middle Assyrian Period (1300 – 1275 BCE), findspot Kalah Shergat, Aššur.

The inscription records the name, titles and conquests of King Adad-Nirari, his father Arik-den-ili, his grandfather Enlil-nirari, and his great-grandfather Ashur-uballit I.

Memorializing the restoration of the Temple of Aššur in the city of Aššur, the text invokes curses upon the head of any king or other person who alters or defaces the monument.

The artifact was purchased from the French Consul in Mosul in 1874 for £70, the British Museum notes reference Mr. George Smith and The Daily Telegraph with an acquisition date of 1874.

Bezold, Carl, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum, IV, London, BMP, 1896.

Furlani, G, Il Sacrificio Nella Religione dei Semiti di Babilonia e Assiria, Rome, 1932.

Rawlinson, Henry C; Smith, George, The Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia, IV, London, 1861.

Budge, E A W, A Guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian Antiquities., London, 1922.

Budge, E A W, The Rise and Progress of Assyriology, London, Martin Hopkinson & Co, 1925.

Grayson, Albert Kirk, Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia BC (to 1115 BC), 1, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1987.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?assetId=32639001&objectId=283138&partId=1

1330 BCE – 1295 BCE: Reign of King Muršili II (Hittite Kingdom).

1126 BCE – 1104 BCE: Reign of King Nebuchadnezzar I (Old Babylonian Period).

1120 BCE: The Sumerian Enuma Elish (creation story) is written.

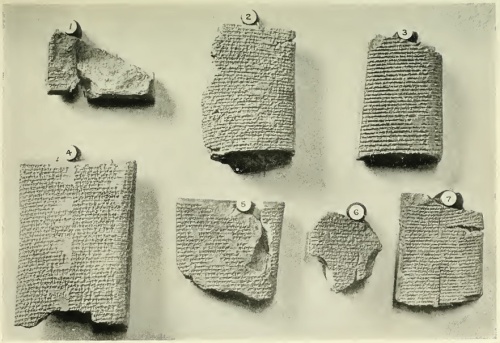

Enuma Elish means “when above”, the two first words of the epic.

This Babylonian creation story was discovered among the 26,000 clay tablets found by Austen Henry Layard in the 1840’s at the ruins of Nineveh.

Enuma Elish was made known to the public in 1875 by the Assyriologist George Adam Smith (1840-76) of the British Museum, who was also the discoverer of the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh. He made several of his findings on excavations in Nineveh.

http://www.creationmyths.org/enumaelish-babylonian-creation/enumaelish-babylonian-creation-3.htm

930 BCE – 612 BCE: Neo-Assyrian Period.

884 BCE – 859 BCE: Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II.

860 BCE – 850 BCE: Reign of King Nabû-apla-iddina (Babylonian Period).

858 BCE – 824 BCE: Reign of King Shalmaneser III.

854 BCE – 819 BCE: Reign of King Marduk-zākir-šumi (Babylonian Period).

823 BCE – 811 BCE: Reign of King Shamsi-Adad V.

810 BCE – 783 BCE: Reign of King Adad-nirari III.

782 BCE – 773 BCE: Reign of King Shalmaneser IV.

772 BCE – 755 BCE: Reign of King Assur-dan III.

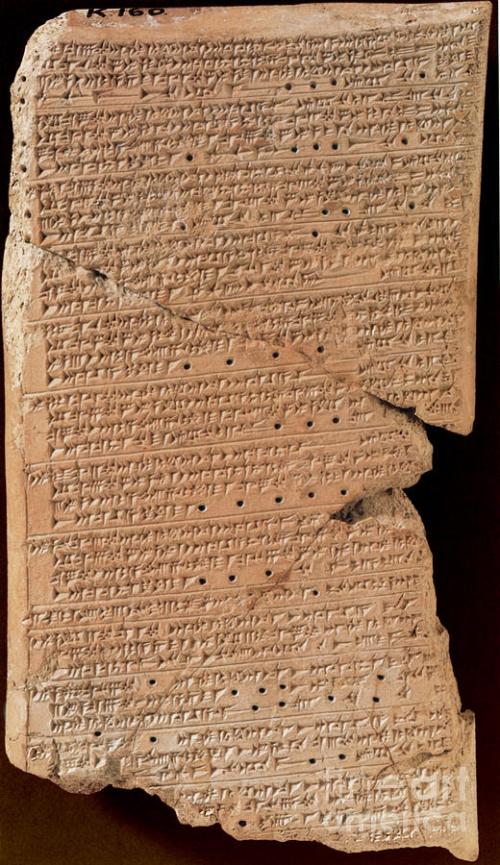

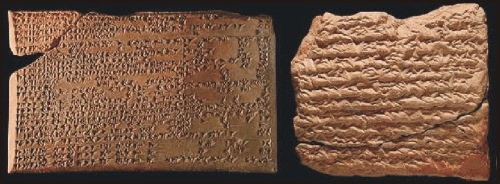

Venus Tablet Of Ammisaduqa, 7th Century

The Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa (Enuma Anu Enlil Tablet 63) refers to a record of astronomical observations of Venus, as preserved in numerous cuneiform tablets dating from the first millennium BC. This astronomical record was first compiled during the reign of King Ammisaduqa (or Ammizaduga), with the text dated to the mid-seventh century BCE.

The tablet recorded the rise times of Venus and its first and last visibility on the horizon before or after sunrise and sunset in the form of lunar dates. Recorded for a period of 21 years, this Venus tablet is part of Enuma anu enlil (“In the days of Anu and Enlil”), a long text dealing with Babylonian astrology, which mostly consists of omens interpreting celestial phenomena.

http://fineartamerica.com/featured/2-venus-tablet-of-ammisaduqa-7th-century-science-source.html

754 BCE – 745 BCE: Reign of King Assur-nirari V.

744 BCE – 727 BCE: Reign of King Tiglath-Pileser III.

726 BCE – 722 BCE: Reign of King Shalmaneser V.

721 BCE – 705 BCE: Reign of King Sargon II.

704 BCE – 681 BCE: Reign of King Sennacherib.

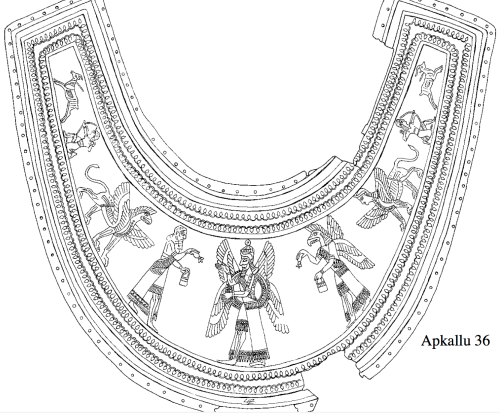

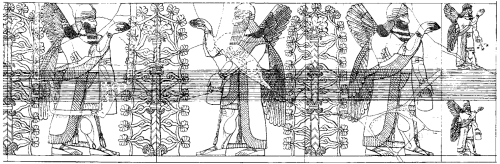

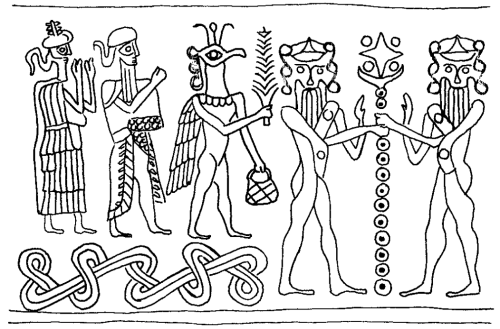

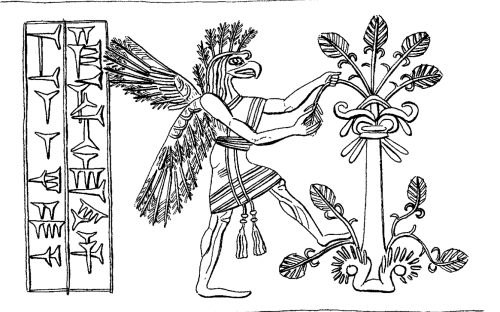

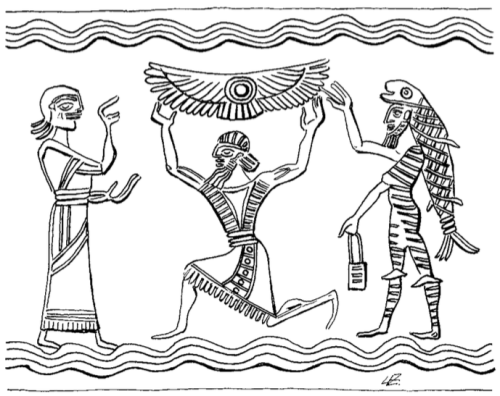

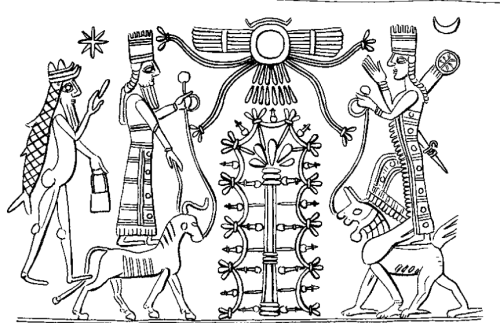

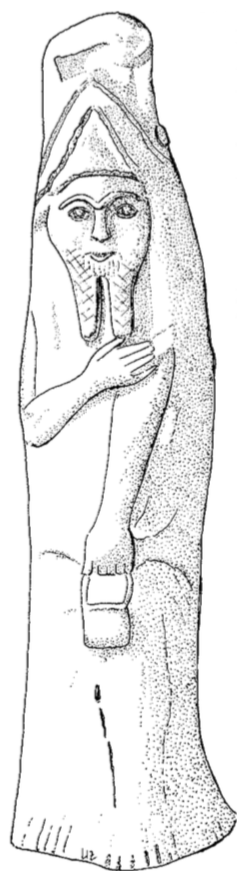

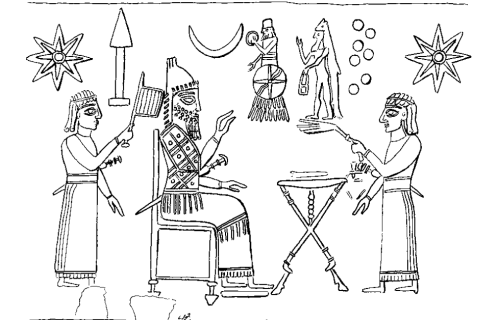

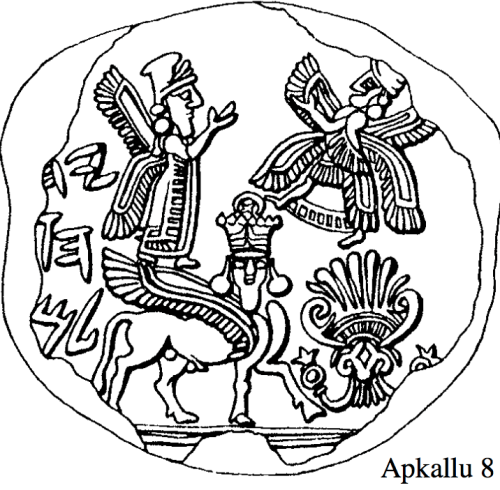

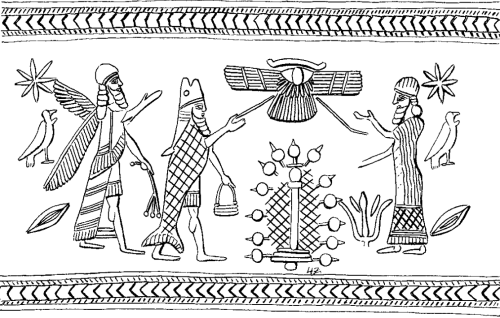

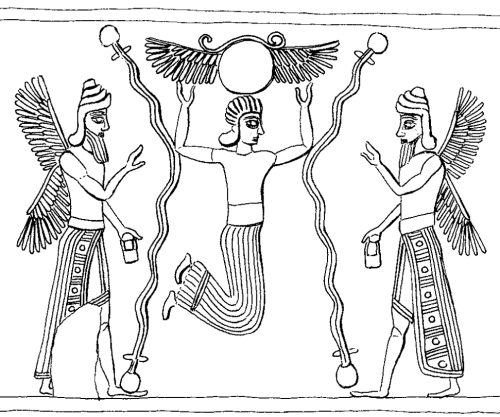

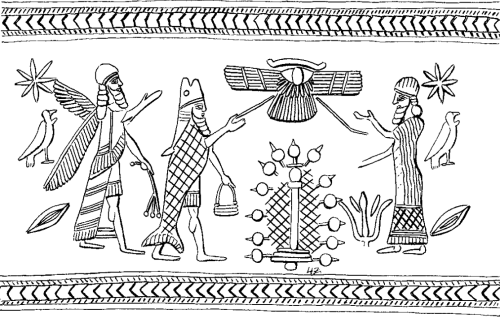

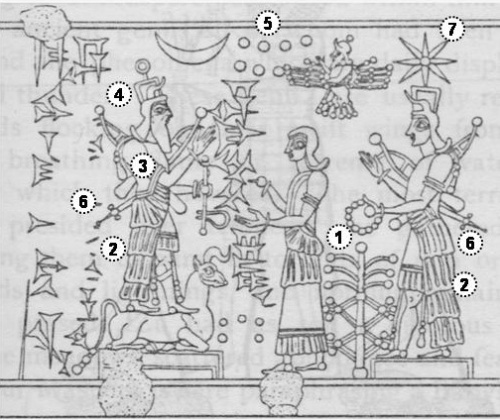

This stone water basin in the collection of the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin came from the forecourt of the Temple of Aššur at Assur. The sides are inscribed with images of Enki / Ea, the Mesopotamian god of wisdom and exorcism, and puradu-fish apkallu. The textual references on the basin refer to the Assyrian king Sennacherib.

The Temple of Aššur was known as the Ešarra, or Temple of the Universe.

The Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-Witchcraft Rituals online notes that water was rendered sacred for ritual purposes by leaving it exposed outside overnight, open to the stars and the purifying powers of the astral deities. The subterranean ocean, or apsû, was the abode of Enki / Ea, and the source of incantations, purification rites and demons, disease, and witchcraft.

Adapted from text © by Daniel Schwemer 2014, (CC BY-NC-ND license).

http://www.cmawro.altorientalistik.uni-wuerzburg.de/magic_witchcraft/gods_stars/

https://books.google.co.th/books?id=LSaeT9CloGIC&pg=PA19&lpg=PA19&dq=water+basin+assur+temple+assur+vorderasiatisches+Museum+Berlin&source=bl&ots=9fw1d16kjb&sig=4ufIF4Ev9MiZl1QUQ8Rv3QU_BZU&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAGoVChMIysSB25rYyAIVUFmOCh1G7QKS#v=onepage&q&f=false

680 BCE – 669 BCE: Reign of King Esarhaddon.

668 BCE – 627 BCE: Reign of King Ashurbanipal.

626 BCE – 539 BCE: Neo-Babylonian Period.

625 BCE – 605 BCE: Reign of King Nabopolassar.

604 BCE – 562 BCE: Reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II.

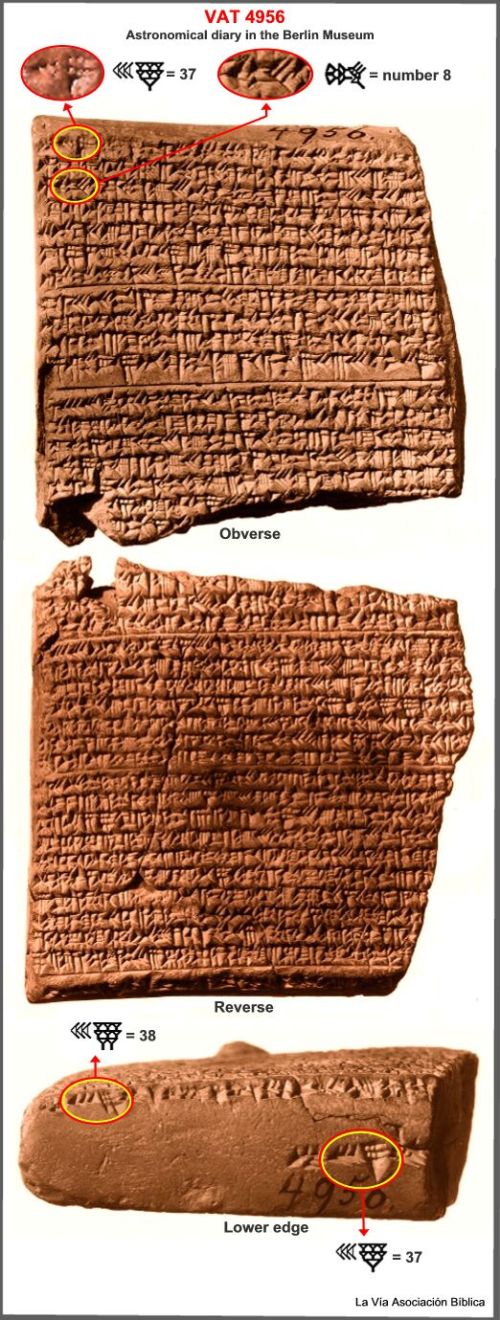

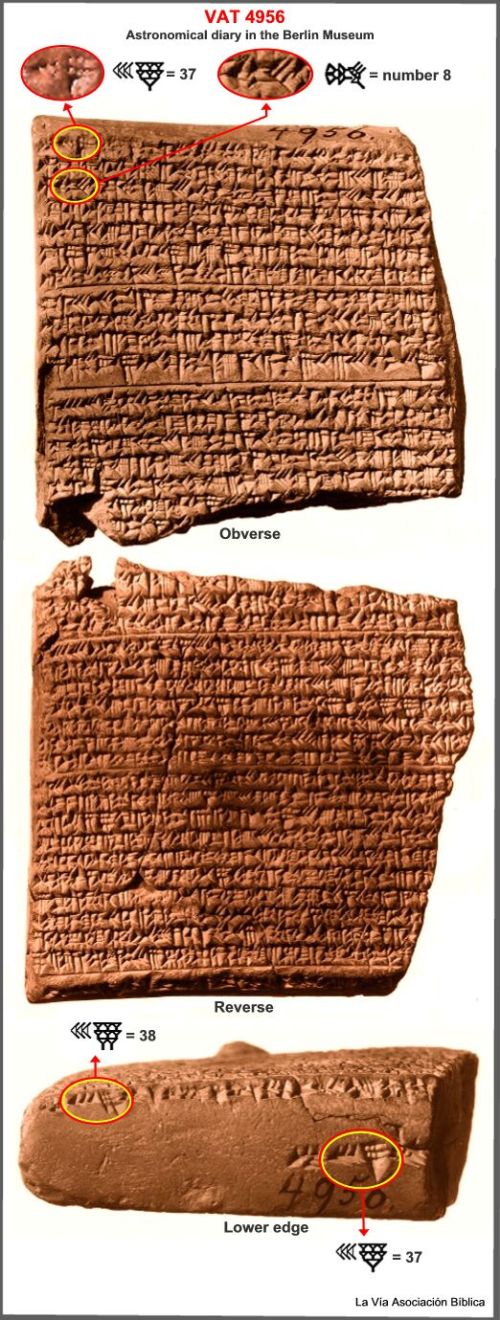

Astronomical Diary VAT 4956 in the collection of the Berlin Museum sets the precise date of the destruction of Jerusalem.

This tablet details the positions of the moon and planets during the year 37 of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, which was 567 BCE. Jerusalem was destroyed in 586 BCE.

http://www.lavia.org/english/archivo/vat4956en.htm

561 BCE – 560 BCE: Reign of King Evil-Merodach.

559 BCE – 556 BCE: Reign of King Neriglissar.

556 BCE: Reign of King Labashi-Marduk.

555 BCE – 539 BCE: Reign of King Nabonidus.

550 BCE – 331 BCE: Achaemenid (Early Persian) Period.

538 BCE – 530 BCE: Reign of King Cyrus II.

529 BCE – 522 BCE: Reign of King Cambyses II.

522 BCE: Reign of King Bardiya.

522 BCE: Reign of King Nebuchadrezzar III.

521 BCE: Reign of King Nebuchadrezzar IV.

521 BCE – 486 BCE: Reign of King Darius I.

485 BCE – 465 BCE: Reign of King Xerxes I.

482 BCE: Reign of King Bel-shimanni.

482 BCE: Reign of King Shamash-eriba.

464 BCE – 424 BCE: Reign of King Artaxerxes.

424 BCE: Reign of King Xerxes II.

423 BCE – 405 BCE: Reign of King Darius II.

404 BCE – 359 BCE: Reign of King Artaxerxes II Memnon.

358 BCE – 338 BCE: Reign of King Artaxerxes III Ochus.

337 BCE – 336 BCE: Reign of King Arses.

336 BCE – 323 BCE: Reign of Alexander the Great (Greek Period, below).

335 BCE – 331 BCE: Reign of King Darius III.

323 BCE – 63 BCE: Seleucid (Hellenistic) Period.

333 BCE – 312 BCE: Macedonian Dynasty.

281 BCE – 261 BCE: Reign of Antiochus I.

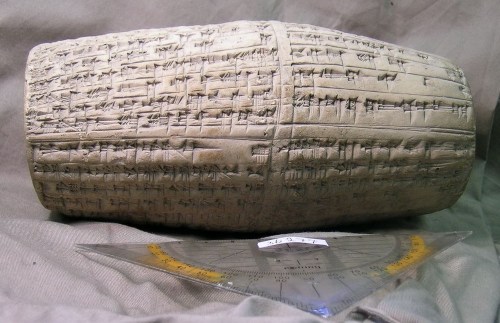

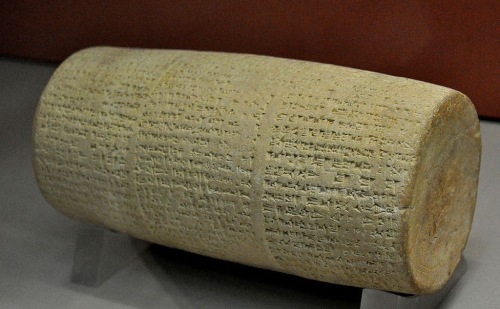

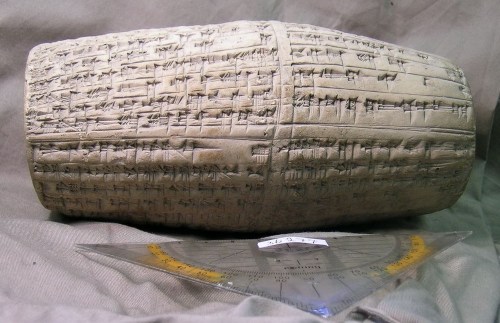

The Cylinder of Antiochus I Soter from the Ezida Temple in Borsippa (Antiochus Cylinder) is an historiographical text from ancient Babylonia, dated 268 BCE, that recounts the Seleucid crown prince Antiochus, the son of king Seleucus Nicator, rebuilding the Ezida Temple.

Lenzi: “The opening lines read: “I am Antiochus, great king, strong king, king of the inhabited world, king of Babylon, king of the lands, the provider of Esagil and Ezida, foremost son of Seleucus, the king, the Macedonian, king of Babylon.”

https://therealsamizdat.com/category/alan-lenzi/

The cuneiform text itself (BM 36277) is now in the British Museum.

The document is a barrel-shaped clay cylinder, which was buried in the foundations of the Ezida temple in Borsippa.

The script of this cylinder is inscribed in archaic ceremonial Babylonian cuneiform script that was also used in the well-known Codex of Hammurabi and adopted in a number of royal inscriptions of Neo-Babylonian kings, including. Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus (cf. Berger 1973).

The script is quite different from the cuneiform script that was used for chronicles, diaries, rituals, scientific and administrative texts.

(Another late example is the Cyrus Cylinder, commemorating Cyrus’ capture of Babylon in 539 BCE (Schaudig 2001: 550-6). This cylinder, however, was written in normal Neo-Babylonian script.)

The Antiochus Cylinder was found by Hormuzd Rassam in 1880 in Ezida, the temple of the god Nabu in Borsippa, in what must have been its original position, “encased in some kiln-burnt bricks covered over with bitumen” in the “doorway” of Koldewey’s Room A1: probably this was built into the eastern section of the wall between A1 and Court A, since the men of Daud Thoma, the chief foreman, seem to have destroyed much of the brickwork at this point.

Rassam (1897: 270) mistakenly records this as a cylinder of Nebuchadnezzar II (Reade 1986: 109). The cylinder is now in the British Museum in London.

(BM 36277).

http://www.livius.org/cg-cm/chronicles/antiochus_cylinder/antiochus_cylinder1.html

This timeline is modified from an original on the ancient.eu site. I added links and illustrations, and tagged and categorized timeframes, which should bring up useful search results when surfing among the tags and categories at the bottom of the page.

I also integrated chronological periods and a selected list of kings from Constance Ellen Gane’s Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, 2012, p. xxii – xxiii, and de-conflicted the entry for the Ur III Period, aka The Sumerian Renaissance, which Gane dates with more precision than the original.

![AM-102 ; No. #1 (K4023) British Museum of London

Tablet K.4023 COL. I [Starting on Line 38] . . . Root of caper which (is) on a grave, root of thorn (acacia) which (is) on a grave, right horn of an ox, left horn of a kid, seed of tamarisk, seed of laurel, Cannabis, seven drugs for a bandage against the Hand of a Ghost thou shalt bind on his temples. FOOTNOTES: [1] - The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 54, No. 1/4 (Oct., 1937), pp. 12-40; Assyrian Prescriptions for the Head By R. Campbell Thompson

http://antiquecannabisbook.com/chap2B/Assyria/K4023.htm](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/k4023-antdiluvian-medical-text.jpg?w=500)

![http://doormann.tripod.com/asssky.htm Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff.](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/assyrian-star-map-from-nineveh.jpg?w=500)