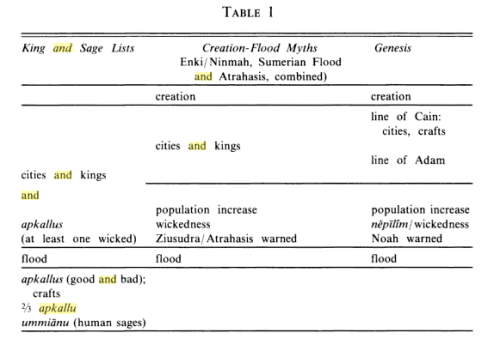

Gane: Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art

“An examination of all the extant, provenanced depictions of composite beings, Mischwesen, in Neo-Babylonian (NB) iconography sheds important new light on the worldview of the last great Mesopotamian civilization.

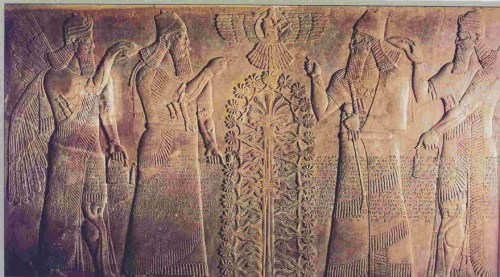

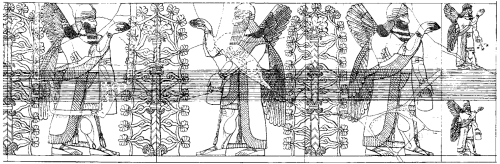

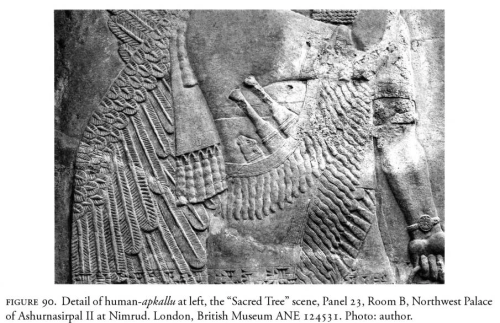

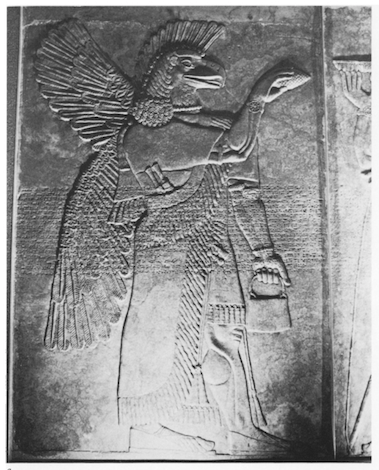

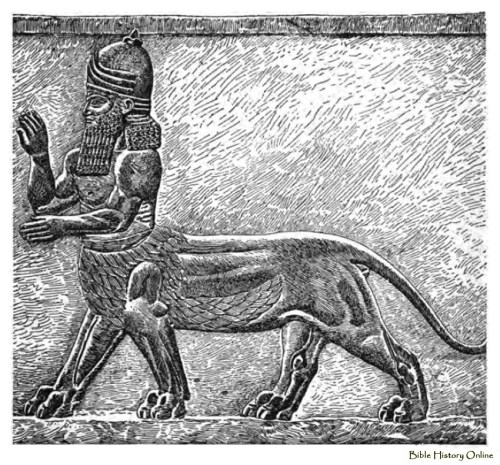

Wall relief depicting a winged and eagle-headed Apkallu (Sage). This protective spirit holds a cone and a bucket for religious ceremonial purposes.

From the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (Biblical Calah; ancient Kalhu), modern day Ninawa Governorate, Iraq (Mesopotamia). Neo-Assyrian period, 865-850 BCE.

The British Museum, London.

Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wall_relief_depicting_an_eagle-headed_and_winged_man,_Apkallu,_from_Nimrud..JPG

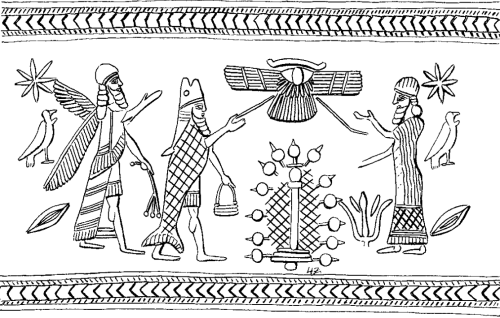

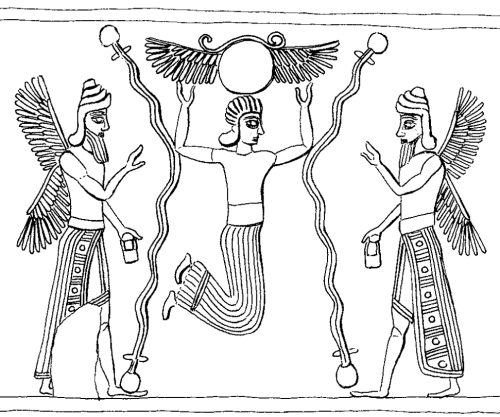

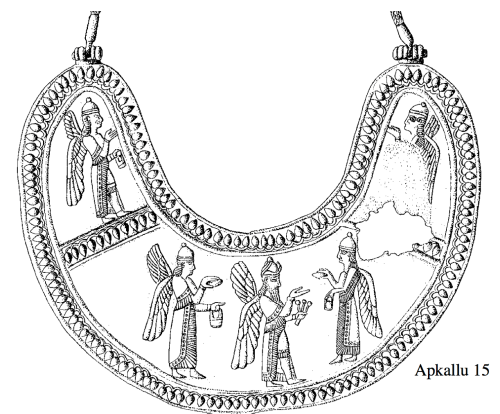

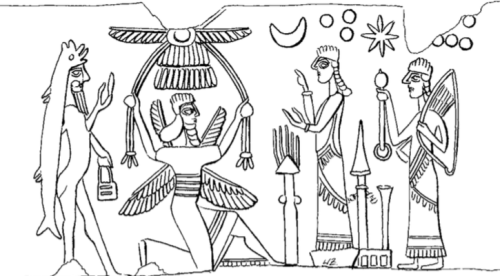

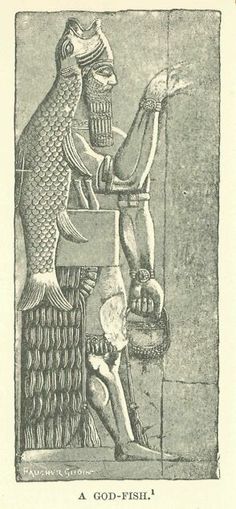

The types of hybrids that are portrayed include such disparate forms as the apkallu and the genius in human form, as well as creatures based on bulls, lions, canines, winged quadrupeds, fish, birds, scorpions, and snakes.

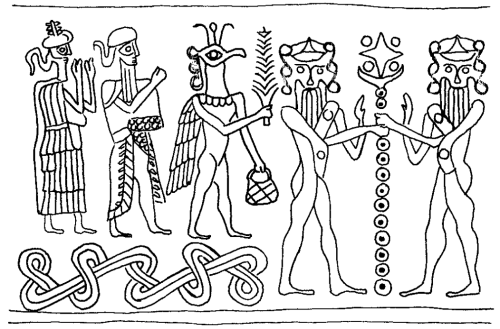

Demons, monsters, and minor apotropaic deities, from Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, Demons & Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, 1992, p. 64.

https://books.google.co.th/books?id=pr8-i1iFnIQC&redir_esc=y

Each composite being is analyzed in terms of its physical components, its context within scenes, its historical development, and its interpretation in NB texts.

Within the hierarchical cosmic community, some lower deities and sub-divine beings appear in composite form. These play a key role in the cosmos by interacting with gods, with each other, with humans, and with natural animals.

Their behavior parallels dynamics found in natural life, such as in competition, conflict, predation, protection, and in the service of others who are more powerful.

In hybrids the capabilities of natural animals and humans are heightened by the selective addition of features derived from other species. There is no consistent correlation, however, between the strength of a natural creature and the relative power of the superhuman being that it symbolizes, or between its physical complexity and its placement in the cosmic hierarchy.

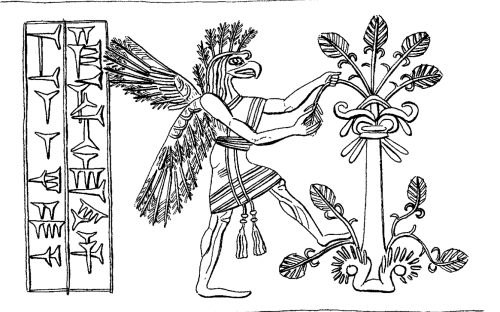

Pazuzu: a demon-god of the underworld, sometimes invoked for beneficial ends. The inscription covering the back of his wings states: “I am Pazuzu, son of Hanpa, king of the evil spirits of the air which issue violently from mountains, causing much havoc.”

Pazuzu was particularly associated with the west wind which brought the plague. Under certain circumstances Pazuzu was a protective spirit, particularly to drive his wife Lamashtu back to the underworld. Lamashtu was a demoness who infected men with various diseases.

Pazuzu first appeared in the 1st millennium BC with the body of a man and the head of a scowling dragon-snake, with two pairs of wings and talons of a bird of prey. He has a scorpion’s tail and his body is covered in scales.

http://wayback.archive.org/web/20090628125910/

http://www.louvre.fr/llv/oeuvres/detail_notice.jsp?CONTENT%3C%3Ecnt_id=10134198673225951&CURRENT_LLV_NOTICE%3C%3Ecnt_id=10134198673225951&FOLDER%3C%3Efolder_id=9852723696500800&baseIndex=56&bmLocale=en

Bronze statuette of Pazuzu, circa 800 BC –- circa 700 BC, Louvre Museum.

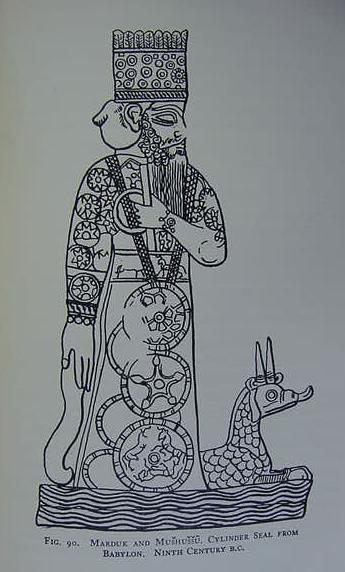

In fact, the transcendence of high gods is often emphasized by their simple representation through attribute animals in natural form.

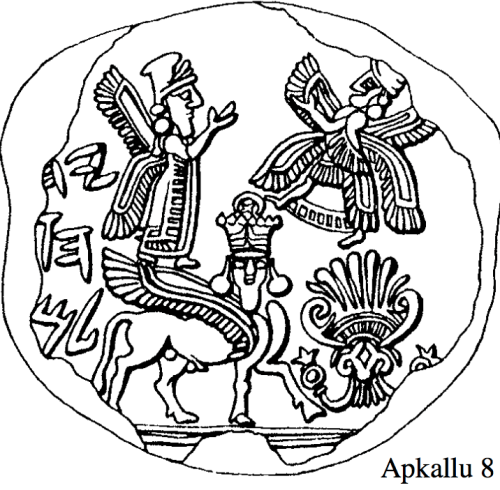

Ishtar receives the worship of an Amazon. Ishtar stands on a lion, holding a bow with arrows at her back. Her eight-pointed star is atop her head.

Lusty antelopes rear on the right side, perhaps signifying the god Ea.

The portrayal of the tree is somewhat problematic, as it differs from the iconic depictions of the sacred tree common in Neo-Assyrian art. Drawing © 2008 S. Beaulieu, after Leick, 1998: Plate 38. Used by kind permission.

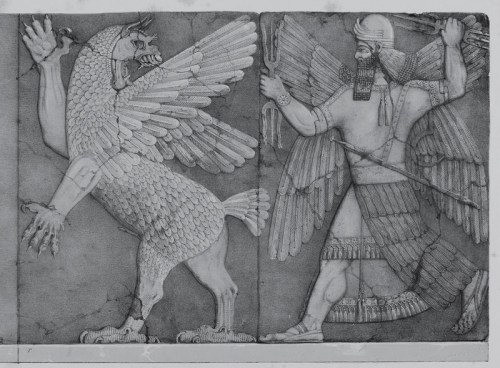

Portrayals of composite beings often express the need for protection from malevolent powers by beneficent beings, some of whom can be accessed only through human mediators, such as ritual functionaries.

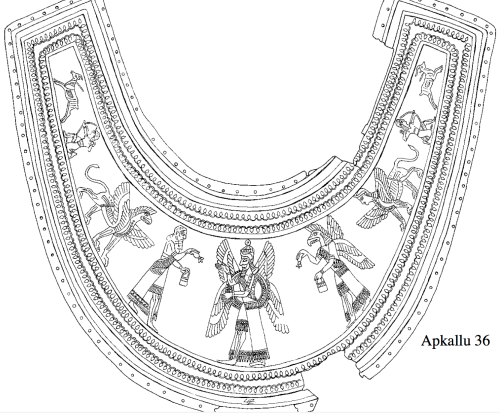

BM 118918, courtesy of the British Museum, plate XId.

Green identifies the ugallu at the center, the “lion-man,” and lahmu at left. He speculates that the “House god” appears at far right.

Limestone relief, one of a pair flanking a doorway in the N. Palace at Nineveh.

Previously published: H.R. Hall, Babylonian and Assyrian Sculptures in the British Museum, Pls. VI-IX; Cf. also Gadd, The Stones of Assyria, 191.

Special relationships between supernatural beings and elite humans, especially the king, make such humans indispensable and therefore support their roles in the existing social order.

It appears that the choice of a particular being portrayed on a given object could be influenced by factors such as its owner’s profession, religious and/or political affiliations, and especially by the apotropaic function(s) of specific composite beings.”

Constance Ellen Gane, Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, Doctoral Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 2012, p. 1.

![AM-102 ; No. #1 (K4023) British Museum of London

Tablet K.4023 COL. I [Starting on Line 38] . . . Root of caper which (is) on a grave, root of thorn (acacia) which (is) on a grave, right horn of an ox, left horn of a kid, seed of tamarisk, seed of laurel, Cannabis, seven drugs for a bandage against the Hand of a Ghost thou shalt bind on his temples. FOOTNOTES: [1] - The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 54, No. 1/4 (Oct., 1937), pp. 12-40; Assyrian Prescriptions for the Head By R. Campbell Thompson

http://antiquecannabisbook.com/chap2B/Assyria/K4023.htm](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/k4023-antdiluvian-medical-text.jpg?w=500)

![In 1847 archaeologists discovered a prism of Sargon dated to the early 8th century BC reading: "At the beginning of my royal rule, I…the town of the Samarians I besieged, conquered (2 Lines destroyed) [for the god…] who let me achieve this my triumph… I led away as prisoners [27,290 inhabitants of it (and) equipped from among them (soldiers to man)] 50 chariots for my royal corps…. The town I rebuilt better than it was before and settled therein people from countries which I had conquered. I placed an officer of mine as governor over them and imposed upon them tribute as is customary for Assyrian citizens." (Nimrud Prism IV 25-41) https://theosophical.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg?w=500)