“The last class of documents undoubtedly contains a very large proportion of the magical ideas, beliefs, formulæ, etc., which were current in Egypt from the time of the Ptolemies to the end of the Roman Period, but from about B.C. 150 to A.D. 200 the papyri exhibit traces of the influence of Greek, Hebrew, and Syrian philosophers and magicians, and from a passage like the following (see Goodwin, Fragment of a Græco-Egyptian Work upon Magic, p. 7) we may get a proof of this:—

“I call thee, the headless one, that didst create earth and heaven, that didst create night and day, thee the creator of light and darkness. Thou art Osoronnophris, whom no man hath seen at any time; thou art Iabas, thou art Iapôs, thou hast distinguished the just and the unjust, thou didst make female and male, thou didst produce seeds and fruits, thou didst make men to love one another and to hate one another.”

“I am Moses thy prophet, to whom thou didst commit thy mysteries, the ceremonies of Israel; thou didst produce the moist and the dry and all manner of food.”

“Listen to me: I am an angel of Phapro Osoronnophris; this is thy true name, handed down to the prophets of Israel. Listen to me. (Here follow a number of names of which Reibet, Athelebersthe, Blatha, Abeu, Ebenphi, are examples) . . .”

In this passage the name Osoronnophris is clearly a corruption of the old Egyptian names of the great god of the dead “Ausar Unnefer,” and Phapro seems to represent the Egyptian Per-âa (literally, “great house”) or “Pharaoh,” with the article pa “the” prefixed.

It is interesting to note that Moses is mentioned, a fact which seems to indicate Jewish influence.

In another magical formula we read, (Goodwin, op. cit., p. 21) “I call upon thee that didst create the earth and bones, and all flesh and all spirit, that didst establish the sea and that shakest the heavens, that didst divide the light from the darkness, the great regulative mind, that disposest everything, eye of the world, spirit of spirits, god of gods, the lord of spirits, the immoveable Aeon, IAOOUÊI, hear my voice.”

“I call upon thee, the ruler of the gods, high-thundering Zeus, Zeus, king, Adonai, lord, Iaoouêe. I am he that invokes thee in the Syrian tongue, the great god, Zaalaêr, Iphphou, do thou not disregard the Hebrew appellation Ablanathanalb, Abrasilôa.”

“For I am Silthakhôoukh, Lailam, Blasalôth, Iaô, Ieô, Nebouth, Sabiothar, Bôth, Arbathiaô, Iaoth, Sabaôth, Patoure, Zagourê, Baroukh Adonai, Elôai, Iabraam, Barbarauô, Nau, Siph,” etc.

The spell ends with the statement that it “loosens chains, blinds, brings dreams, creates favour; it may be used in common for whatever purpose you will.”

In the above we notice at once the use of the seven vowels which form “a name wherein be contained all Names, and all Lights, and all Powers” (see Kenyon, Greek Papyri in the British Museum, London, 1893, p. 63). The seven vowels have, of course, reference to the three vowels “Iaô” (for Iaoouêi we should probably read Iaô ouêi) which were intended to represent one of the Hebrew names for Almighty God, “Jâh.”

The names “Adonai, Elôai,” are also derived through the Hebrew from the Bible, and Sabaôth is another well-known Hebrew word meaning “hosts”; some of the remaining names could be explained, if space permitted, by Hebrew and Syriac words.

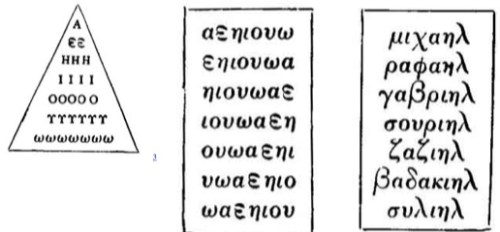

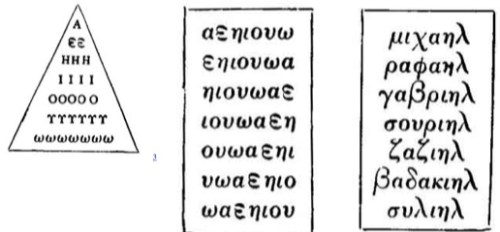

On papyri and amulets the vowels are written in magical combinations in such a manner as to form triangles and other shapes; with them are often found the names of the seven archangels of God; the following are examples:–

(British Museum, Gnostic gem, No. G. 33).

(Kenyon, Greek Papyri, p. 123).

(Ibid., p. 123. These names read Michael, Raphael, Gabriel, Souriel, Zaziel, Badakiel, and Suliel)

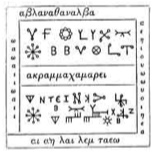

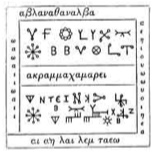

In combination with a number of signs which owe their origin to the Gnostics the seven vowels were sometimes engraved upon plaques, or written upon papyri, with the view of giving the possessor power over gods or demons or his fellow creatures.

The example printed below is found on a papyrus in the British Museum and accompanies a spell written for the purpose of overcoming the malice of enemies, and for giving security against alarms and nocturnal visions. (Kenyon, op. cit., P. 121).

Amulet inscribed with signs and letters of magical power for overcoming the malice of enemies. (From Brit. Mus., Greek Papyrus, Nu. CXXIV.–4th or 5th century.) (Kenyon, Greek Papyri, p. 123).

But of all the names found upon Gnostic gems two, i.e., Khnoubis (or Khnoumis), and Abrasax (or Abraxas), are of the most frequent occurrence. The first is usually represented as a huge serpent having the head of a lion surrounded by seven or twelve rays.

Over the seven rays, one on the point of each, are the seven vowels of the Greek alphabet, which some suppose to refer to the seven heavens; and on the back of the amulet, on which the figure of Khnoumis occurs, is usually found the sign of the triple S and bar.

Khnoumis is, of course, a form of the ancient Egyptian god Khnemu, or “Fashioner” of man and beast, the god to whom many of the attributes of the Creator of the universe were ascribed.

Khnemu is, however, often depicted with the head of a ram, and in the later times, as the “beautiful ram of Râ,” he has four heads; in the Egyptian monuments he has at times the head of a hawk, but never that of a lion.

The god Abrasax is represented in a form which has a human body, the bead of a hawk or cock, and legs terminating in serpents; in one hand he holds a knife or dagger, and in the other a shield upon which is inscribed the great name ΙΑΩ {Greek IAW}, or JÂH.

Considerable difference of opinion exists as to the meaning and derivation of the name Abrasax, but there is no doubt that the god who bore it was a form of the Sun-god, and that he was intended to represent some aspect of the Creator of the world.

The name was believed to possess magical powers of the highest class, and Basileides, (he of Alexandria, who lived about A.D. 120. He was a disciple of Menander, and declared that he had received the esoteric doctrine of Saint Peter from Glaucias, a disciple of the Apostle) who gave it currency in the second century, seems to have regarded it as an invincible name.

It is probable, however, that its exact meaning was lost at an early date, and that it soon degenerated into a mere magical symbol, for it is often found inscribed on amulets side by side with scenes and figures with which, seemingly, it cannot have any connexion whatever.

Judging from certain Gnostic gems in the British Museum, Abrasax is to be identified with the polytheistic figure that stands in the upper part of the Metternich stele depicted on p. 153 and below.

Metternich Stele.

This figure has two bodies, one being that of a man, and the other that of a bird; from these extend four wings, and from each of his knees projects a serpent.

He has two pairs of hands and arms; one pair is extended along the wings, each hand holding the symbols of “life,” “stability,” and “power,” and two knives and two serpents; the other pair is pendent, the right hand grasping the sign of life, and the other a sceptre.

His face is grotesque, and probably represents that of Bes, or the sun as an old man; on his head is a pylon-shaped object with figures of various animals, and above it a pair of horns which support eight knives and the figure of a god with raised hands and arms, which typifies “millions of years.”

The god stands upon an oval wherein are depicted figures of various “typhonic” animals, and from each side of his crown proceed several symbols of fire.

Whether in the Gnostic system Abraxas absorbed all the names and attributes of this god of many forms cannot be said with certainty.”

E.A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Magic, London, 1901. P. 177-80.