Kvanvig: The ilū mušīti Are the Stars of the Night

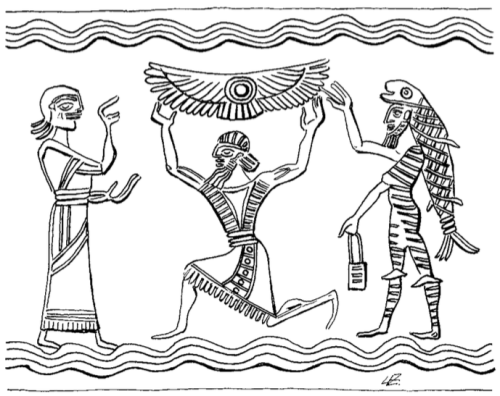

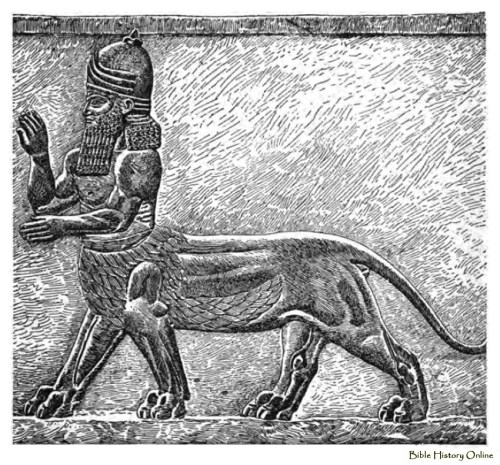

“How the actual connection between the earthly exorcist and his heavenly counterpart was imagined is vividly portrayed on an Assyrian bronze tablet from the first millennium.

A depiction of the underworld, or alternatively, a portrayal of an exorcism.

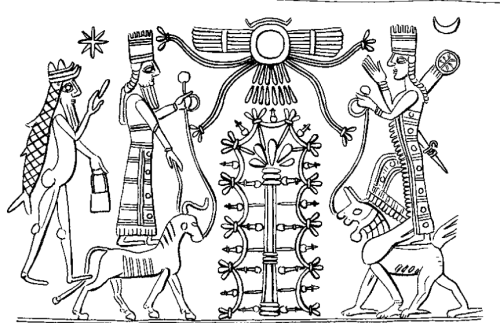

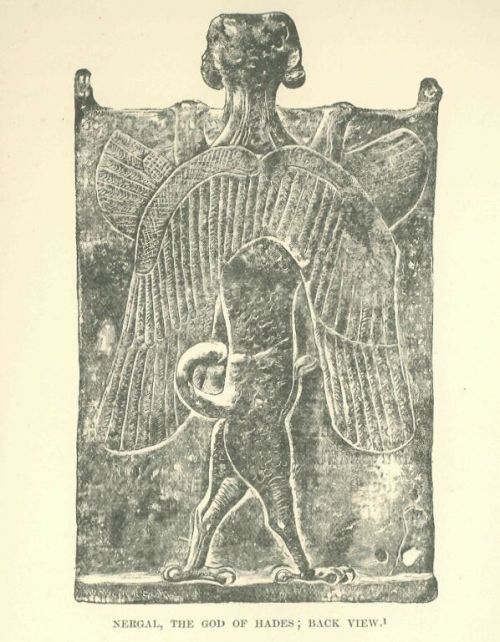

Wiggermann identifies Pazuzu appearing at the top, leering over a top register which contains the eight-pointed star of Ishtar, the inverted half-moon crescent of the Moon God Sin, and the lamp of Nusku. The seven celestial objects of Babylonian cosmogony are at far right, above Nusku’s lamp. Earlier analysts identified the leering monster as Nergal. Virtually all subsequent scholars now follow Wiggermann.

In the second register, seven exemplars of the Mesopotamian pandemonium appear to support the heavens. These composite creatures include ugallu, lion headed monsters with an apotropaic function, among others.

The middle register could portray burial rites for new arrivals in the underworld, presided over by two fish-apkallū, or the scene could be a typical exorcism for apkallu, who played a role in banishing demons from the ill.

In this register Wiggermann identifies the lion headed monsters as ugallu and the human-appearing entity as Lulal, a “minor apotropaic god.”

The lower register was formerly considered to depict the goddess Allat, or Ereshkigal, sister of Ishtar, who reigns in the underworld. Wiggermann prefers Lamaštu, and he is persuasive.

Lamaštu kneels upon a horse or a donkey, which appears to be oppressed by her burden, throttling snakes in each hand, in a boat which floats upon the waters of life.

Note the lion pups suckling at her breast.

Wiggermann considers this 1st millennium amulet a portrayal of a Lamaštu exorcism.

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a bronze plaque of which an engraving was published by Clermont-Ganneau.

The original, which belonged to M. Péretié, is now in the collection of M. de Clercq.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17323/17323-h/17323-h.htm#linkBimage-0039

The image depicts the universe of an ill man. In the basement lurks the demon Lamaštu, ready to attack; in the upper room are divine figures supporting the heavens, filled with the symbols of the highest gods; in between lies the sick man on his bed with his arm stretched out toward heaven.

At his head and at his feet two figures with human bodies and fish cloaks are placed, performing a ritual. (Cf. O. Keel, Die Welt der altorientalischen Bildsymbolik und das Alte Testament, 3 ed. Darmstadt, 1984, 68f.)

One could think that these figures actually were āšipū, dressed in ritual clothes as fish-apkallus. This is hardly the case; we do not have any evidence that the āšipū used fish-cloaks as ritual dress. The depiction rather shows the presence of the transcendent apkallus in the ritual, as “guardian angels” of the sick man.

This is the actual bronze frieze of the illustration above, held in the collection of the Louvre as AO 22205.

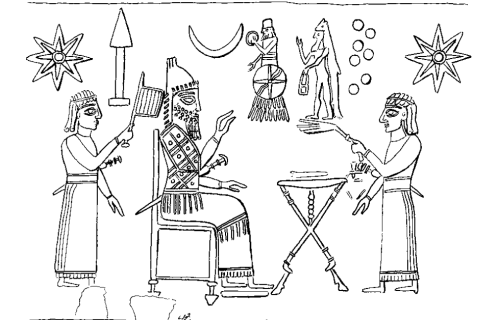

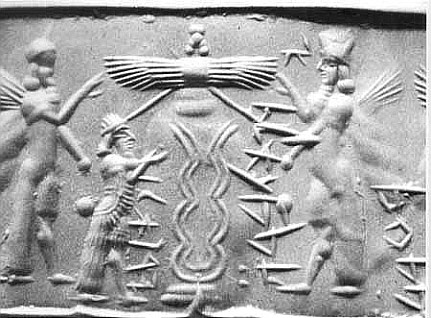

The apkallus appear in the rituals of the day. Twice in our material they are paired with what generally can be designated as ilū mušīti, “the gods of the night.” Both in Bīt Mēseri and in the Mīs pî ritual we will deal with below, the ritual extends over night and day.

The ilū mušīti are the stars of the night; they sometimes represent a deification of celestial constellations and planets, other times a deification of the great deities who in this case are addressed as stars. (Cf. Erica Reiner, Astral Magic in Babylonia, vol. 85, TAPhs. Philadelphia 1995, 5-6.)

“Stand by me, O Gods of the Night!

Heed my words, O gods of destinies,

Anu, Enlil, and all the great gods!

I call to you, Delebat (i.e. Venus), Lady of battles (variant has: Lady of the silence [of the night]),

I call to you, O Night, bride (veiled by?) Anu.

Pleiades, stand on my right, Kidney star, stand on my left.”

(Apotropaic Ritual, KAR 38: 12f).

The stars represent the heavenly counterpart to the earth. Just as the night among humans is divided into three watches, the stars are called massarātu ša mūši, “the watches of the night:”

“May the star itself take to you (goddess) my misery;

let the ecstatic tell you, the dream interpreter repeat to you,

let the (three) watches of the night speak to you . . .

(Apotropaic Ritual, KAR 38 rev. 24f).

May the watches of the night tell you

That I did not sleep, I did not lie down, did not groan, did not arise,

But that my tears were made my food.”

(Psalm of Penitence, Assur II, 2-4)

G. Lambert, “The Sultantepe Tablets, a Review Article,” RA 80 1959, 119-38, 127.

The stars keep watch over both those awake and those sleeping in the night. In the following prayer to the stars there is play on the connotations of “watching,” massartu / nasāru, and êru, “be awake:”

“(you) three watches of the night

you are the wakeful, watchful, sleepless, never sleeping ones–

as you are awake, watchful, sleepless, never sleeping,

you decide the fate of those awake and sleeping (alike).”

(Prayer to the Stars, KAR 58 rev. 12f.)

In several cases the stars are invoked together with two typical night deities in late Assyrian and Late Babylonian times, Girra, the god of fire, and Nusku, the god of lamp and fire.”

(Cf. J. Black and A. Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, London: 1992, 88, 145. For Nusku, cf. also D. Schwemer, Abwehrzauber und Behexung, Wiesbaden: 2007, 38, 54-5, 146, 206-7.)

Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011, pp. 133-4.