Eco: Francis Lodwick

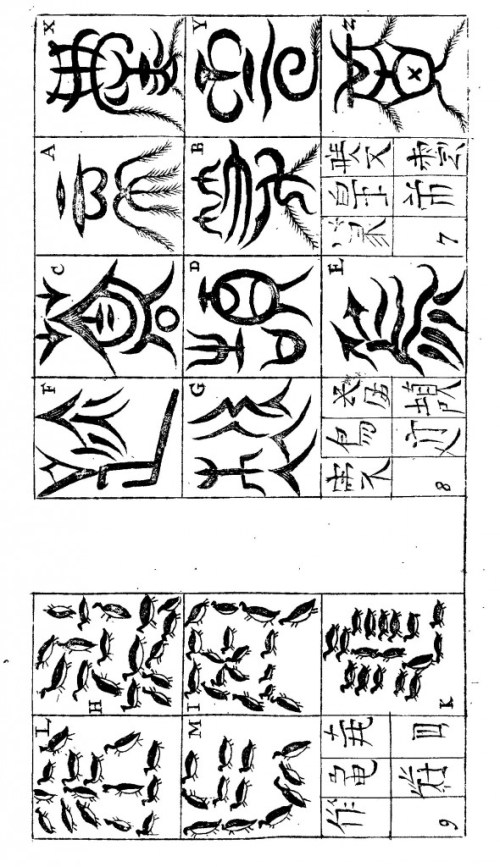

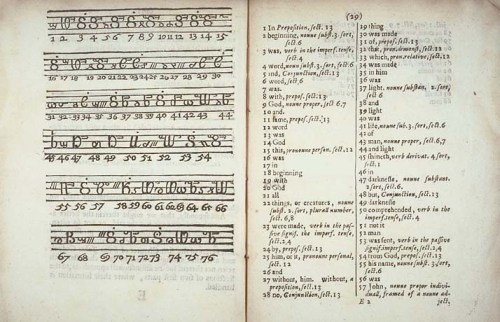

Francis Lodwick (1619-1694), eight verses from the first chapter of the Gospel of St. John in Francis Lodwick’s common writing, next to the numerical key composed for it. A Common Writing, London, 1647. Museum of the History of Science, University of Oxford. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“Lodwick wrote before either Dalgarno or Wilkins, both of whom had thus the opportunity to know his work. Salmon (1972: 3) defines him as the author of the first attempt to construct a language in universal character. His first work, A Common Writing, appeared in 1647; The Groundwork or Foundation Laid (or So Intended) for the Framing of a New Perfect Language and a Universal Common Writing dates from 1652.

Lodwick was not a learned man–no more than a merchant, as he humbly confessed. Though, in his Ars signorum, Dalgarno praised Lodwick for his endeavors, he was unable to hold back the supercilious observation that he did not possess the force adequate so such an undertaking, being a man of the arts, born outside of the Schools (p. 79).

In his writings, Lodwick advanced a number of proposals, some more fruitful than others, on how to delineate a language that would both facilitate commercial exchange and permit the easy acquisition of English.

His ideas, moreover, changed over time, and he never managed to design a complete system. None the less, certain of what appears in the most original of his works (A Common Writing, hardly thirty pages long) reveals him as striking off in a direction very different from other authors of his time, making him a precursor of certain trends of contemporary lexical semantics.

In theory, Lodwick’s project envisioned the creation of a series of three numbered indexes; the purpose of these was to refer English words to the character and these to its words. What distinguished Lodwick’s conception from those of the polygraphers, however, was the nature of its lexicon.

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, Figure 13.1, p. 261.

Lodwick’s idea was to reduce the number of terms contained in the indexes by deriving as many of them as possible from a finite number of primitives which express actions. Figure 13.1 shows how Lodwick chooses a conventional character (a sort of Greek delta) to express the action of drinking; then, by adding to this radix different grammatical marks, makes the different composite characters express ideas such as the actor (he who drinks), the act, the object (that which is drunk), the inclination (the drunkard), the abstraction, and the place (the drinking house, or tavern).

From the time of Aristotle up until Lodwick’s own day, names of substances had invariably been the basis upon which a structure of classification had been erected. Lodwick’s original contribution, however, was to commence not with substantives but with verbs, or schemes of actions, and to populate these schemes with roles–what we would now call actants–such as agent, object, place and so on.

Lodwick designed his characters to be easily recognized and remembered: as we have seen, to drink was specified by a sort of Greek delta, while to love was a sort of L. The punctuation and added notes are vaguely reminiscent of Hebrew. Finally, as Salmon suggests, Lodwick probably took from contemporary algebra the idea of substituting letters for numbers.

In order to set up his finite packet of radicals Lodwick devised a philosophical grammar in which even grammatical categories expressed semantic relations. Derivatives and morphemes could thus become, at the same time, criteria of efficiency to reduce each grammatical category further to a component of action.

By such means the number of characters became far small than the words of a natural language found in a dictionary, and Lodwick endeavored to reduce this list further by deriving his adjectives and adverbs from the verbs.

From the character to love, for example, he derived not only the object of the action (the beloved) but also its mode (lovingly); by adding a declarative sign to the character to cleanse, he asserted that the action of cleansing has been performed upon the object–thereby deriving the adjective clean.

Lodwick realized, however, that many adverbs, prepositions, interjections and conjunctions were simply not amenable to this sort of derivation; he proposed representing these as notes appended to the radicals. He decided to write proper names in natural languages.

He was embarrassed by the problem of “natural kinds” (let us say, names of substances like cat, dog, tree), and resigned himself to the fact that, here, he would have to resort to a separate list. But since this decision put the original idea of a severely limited lexicon in jeopardy, he tried to reduce the list of natural kinds as much as possible, deciding that terms like hand, foot or land could be derived from actions like to handle, to foot or to land.

In other cases, he resorted to etymology, deriving, for instance, king from the archaic radical to kan, claiming that it meant both to know and to have power to act. He pointed out that Latin rex was related to the verb regere, and suggested that both the English king and the German emperor might be designated by a simple K followed by the name of the country.

Where he was not able to find appropriate verbal roots, he tried at least to reduce as many different sounds as possible to a single root. He thus reduced the names for the young of animals–child, calfe, puppy, chikin–to a single root.

Moreover, Lodwick thought that the reduction of many lexical items to a unique radical could also be performed by using analogies (seeing as analogous to knowing), synonymy (to lament as a synonym of to bemoane), opposition (to curse as the opposite of to bless), or similarities in substance (to moisten, to wet, to wash and even to baptize are all reduced to moisture).

All these derivations were to be signaled by special signs. Wilkins had had a similar idea when proposing the method of transcendental particles, but it seems that Lodwick’s procedure was less ambiguous.

Lodwick barely sketched out his project; his system of notation was cumbersome; nevertheless (with a bare list of sixteen radicals–to be, to make, to speake, to drinke, to love, to cleanse, to come, to begin, to create, to light, to shine, to live, to darken, to comprehend, to send and to name), he managed to transcribe the opening of the gospel of St. John (“In the Beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God . . .”).

Beginning was derived of course from to begin, God from to be, Word from to speake, and so on (the idea of all things is derived from to create).

Just as the polygraphers had taken Latin grammar as a universal model, so Lodwick did the same for English–though his English grammatical categories still reflected the Latin model. Nevertheless he succeeded in avoiding certain limits of the Aristotelian classification of substances, because no previous tradition obliged him to order an array of actions according to the rigid hierarchical schema requested by a representation of genera and species.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 260-3.