Babylon: Imperial Polytheism

“As long, however, as these multitudinous deities were believed to exist, so long was it also believed that they could injure or assist. Hence come such expressions as those which meet us in the Penitential Psalms, “To the god that is known and that is unknown, to the goddess that is known and that is unknown, do I lift my prayer.”

Hence, too, the care with which the supreme Baal was invoked as “lord of the hosts of heaven and earth,” since homage paid to the master was paid to the subjects as well.

Hence, finally, the fact that the temples of the higher gods, like the Capitol at Rome, became gathering places for the inferior divinities, and counterparts on the earth of “the assembly of the gods” in heaven.

That curious product of Mandaite imagination, the Book of Nabathean Agriculture, which was translated into Arabic by Ibn Wahshiya in the 10th century, sets before us a curious picture of the temple of Tammuz in Babylon.

“The images (of the gods),” it tells us,

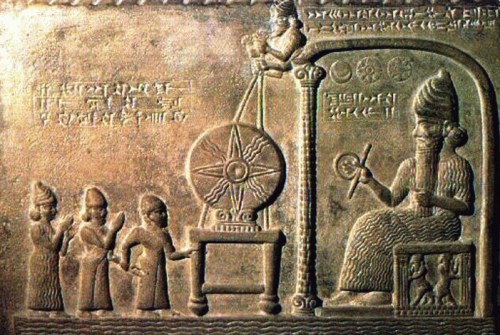

“congregated from all parts of the world to the temple of el-Askûl (Ê-Sagil) in Babylon, and betook themselves to the temple (haikal) of the Sun, to the great golden image that is suspended between heaven and earth in particular.

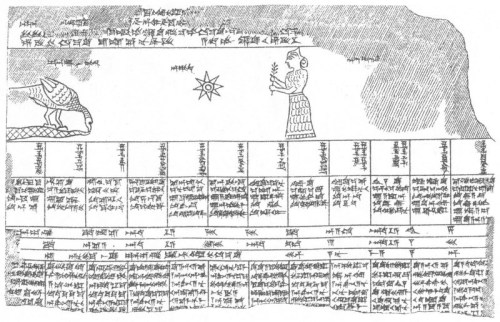

The image of the sun stood, they say, in the midst of the temple, surrounded by all the images of the world. Next to it stood the images of the sun in all countries; then those of the moon; next those of Mars; after them the images of Mercury; then those of Jupiter; next of Venus; and last of all, of Saturn.

Thereupon the image of the sun began to bewail Tammuz and the idols to weep; and the image of the sun uttered a lament over Tammuz and narrated his history, whilst the idols all wept from the setting of the sun till its rising at the end of that night. Then the idols flew away, returning to their own countries.”

The details are probably borrowed from the great temple of pre-Mohammedan Mecca, but they correspond very faithfully with what we now know the interior of one of the chief temples of Babylonia and Assyria to have been like.

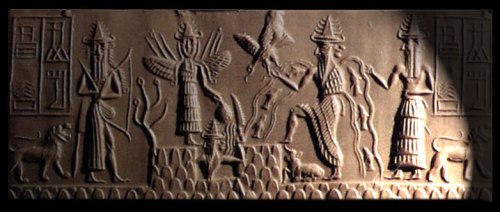

Fragments have been preserved to us of a tablet which enumerated the names of the minor deities whose images stood in the principal temples of Assyria, attending like servants upon the supreme god.

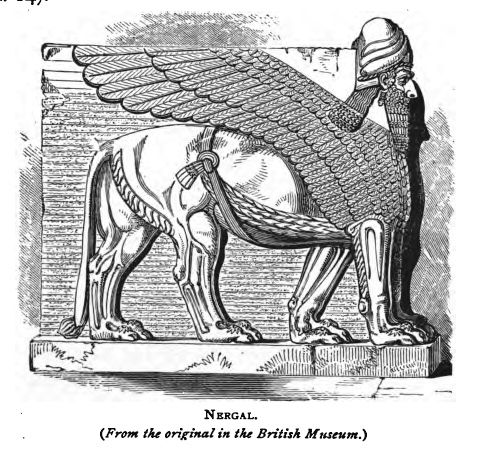

Among them are the names of foreign divinities, to whom the catholic spirit of Babylonian religion granted a place in the national pantheon when once the conquest of the towns and countries over which they presided had proved their submission to the Babylonian and Assyrian gods; even Khaldis, the god of Ararat, figures among those who dwelt in one of the chief temples of Assyria, and whose names were invoked by the visitor to the shrine.

Ḫaldi was the chief deity of the Ararat (Urartu) pantheon. His shrine at Ardini (likely from Armenian Artin), was in Akkadian Muṣaṣir (Exit of the Serpent/Snake).

Of all the gods of the Ararat (Urartu) pantheon, most inscriptions are dedicated to Khaldi or Hayk (Armenian: Հայկ) or Hayg, also known as Haik Nahapet (Հայկ Նահապետ, Hayk the Tribal Chief), the legendary patriarch of the Armenian nation.

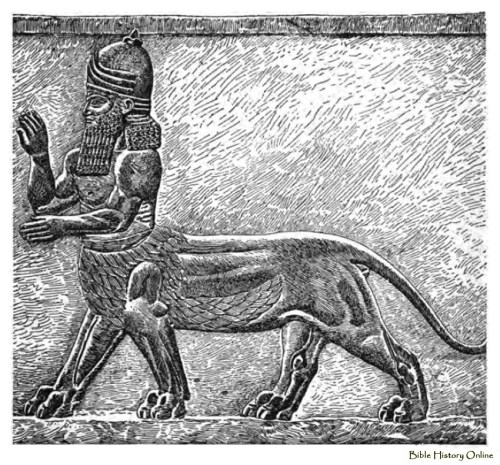

He is portrayed as a man standing on a lion.

The kings of Urartu prayed to Khaldi for victory in battle. Temples dedicated to Khaldi were adorned with weapons.

https://aratta.wordpress.com/2014/10/25/kaldikali-hel/

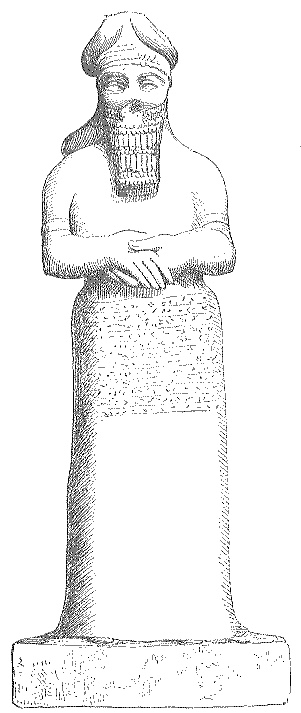

The spectacle of such a temple, with the statue or symbol of the supreme Baal rising majestically in the innermost cell, and delivering his oracles from within the hidden chamber of that holy of holies, while the shrines of his wife and offspring were grouped around him, and the statues of ministering deities stood slave-like in front, was a fitting image of Babylonian religion.

“The gods many and lords many” of an older creed still survived, but they had become the jealously-defined officials of an autocratic court. The democratic polytheism of an earlier day had become imperial.

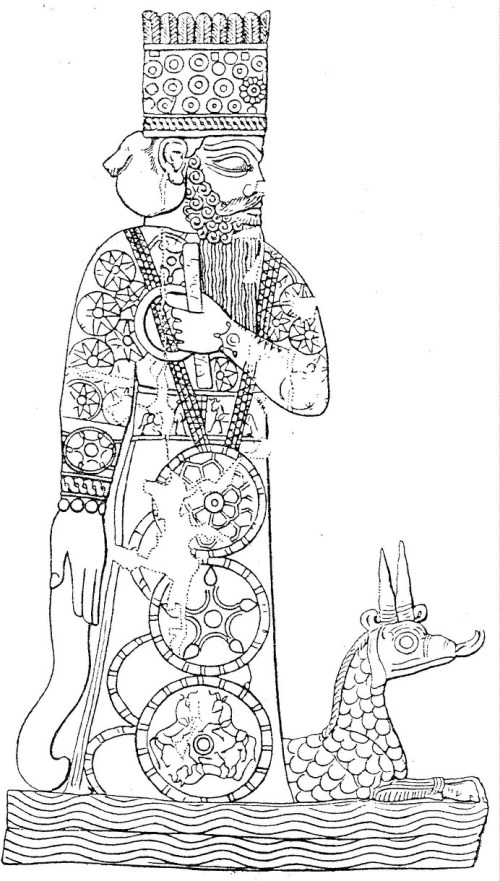

Bel was the counterpart of his vicegerent the Babylonian king, with this difference, that whereas Babylonia had been fused into an united monarchy, the hierarchy of the gods still acknowledged more than one head.

How long Anu and Ea, or Samas and Sin, would have continued to share with Merodach the highest honours of the official cult, we cannot say; the process of degradation had already begun when Babylonia ceased to be an independent kingdom and Babylon the capital of an empire.

Merodach remained a supreme Baal–the cylinder inscription of Cyrus proves so much–but he never became the one supreme god.”

A.H. Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians, 5th ed., London, 1898, pp. 217-20.

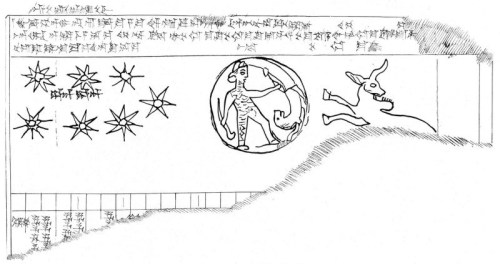

![Assyrian star map from Nineveh (K 8538). Counterclockwise from bottom: Sirius (Arrow), Pegasus + Andromeda (Field + Plough), [Aries], the Pleiades, Gemini, Hydra + Corvus + Virgo, Libra. Drawing by L.W.King with corrections by J.Koch. Neue Untersuchungen zur Topographie des Babilonischen Fixsternhimmels (Wiesbaden 1989), p. 56ff. http://doormann.tripod.com/asssky.htm](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/assyrian-star-map-from-nineveh.jpg?w=500)