Examples of Magic in the Filāha

“The magical recipes and forms of action in Filāha are in harmony with the magic of the area since the Hellenistic period. Very prominent in the Nabatean corpus is the preparation of magical images. One of the rare occurrences of black magic in Filāha describes the preparation of an image of a man or woman, to be inscribed with his/her name, and an image of a poisonous animal, or a voracious beast, attacking him/her.

The preparation of this image leads to the instant sickness or madness of the victim (Filāha, p. 147) — the purported author, though, quickly, makes it clear that he personally would never harm anybody by magic, neither an animal nor a human being like himself.

Yet he does not dare speak openly against magicians because of their harmful power (p. 147). The same claim is repeated on p. 322, where the purported author identifies his enemies as the followers of Īshīthā, son of Ādamā.

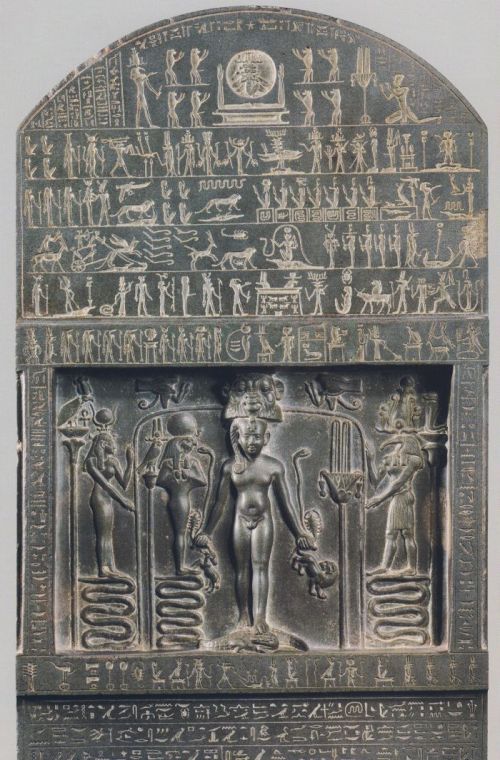

Magical images are also used against harmful animals. Thus, Filāha, p. 414, II. 3-14, advises how to make an image against birds–in fact, this image might even work, as it is basically a scarecrow. In yet another recipe one needs blood and some soil from a burial ground, and from this dough «you make an image (sūra) with outstretched arms like a crucified man (maslūb)».

Another typical Near Eastern magical action, hanging a talisman on the doorpost, is also known to the author (Filāha, p. 582) and used to ward off harmful animals, like snakes, scorpions and wasps, as well as thieves, etc.

In some of the recipes, the magical and the medicinal aspects are often difficult to keep separate. In many cases, the preparation includes no magical actions and, whether effective from a modern point of view or not, they clearly belong to the sphere of medicine.

In other cases, different prayers and magical actions, including an astrologically selected time and place for producing the preparation, make the product magical, although one has to be aware of the importance of astrology also in «normal» medicine.

Thus, in Filāha, p. 583, there is a recipe against toothache which involves magical actions: after having prepared seven pills (bunduq) according to instructions, one takes them in his ieft hand and turning towards the moon on the twenty-fourth night of the month, takes one pill in his right hand and addresses the moon saying: «I prepared these pills as an offering (qurbān) to you so that you would cause the ache in my teeth to calm down and would strengthen my gums».

Then he must throw the pills, one by one, towards the moon. In this case, the preparation is not even consumed and its effect is solely magical, in contrast to a preparation for sexual potency, given on the same page, which falls quite clearly within the boundaries of medicine and lacks any signs of magical operations.

The purported author, Qūthāmā, also knows of popular tricksters who perform magic-like acts of entertainment. In Filāha, p. 487, he mentions a trick (hīla) of jugglers (musha ’bidhīn) who take a handful of rice and throw it into a basin full of snakes, which makes the snakes stand on their tails and dance.

This is what «the people of phantasm (khayālāt) and sleight of hand (sihr al- ‘ayn) among magicians (sahara) do». These snake charmers were obviously real performers seen by the author.”

Jaakko Hāmeem-Anttila, “Ibn Wahshiyya and Magic,” Anaquel de Estudios Árabes X, 1999, pp. 46-7.