Berossus was a Historian and a Priest of Bel, Not a Babylonian Astronomer

“As de Breucker has emphasized, one goal of the Babyloniaca was to promote Babylonian antiquity and scholarship. We should see the so-called astronomical fragments in this light, as part of his promotion of Babylonian scholarship.

However, it is clear that Berossos was not himself one of the astronomical scribes working in Babylonia. All of the astronomy he explains has its origin not in contemporary Babylonian astronomy, but in works such as Enūma Eliš, a literary epic that includes a brief cosmological section.

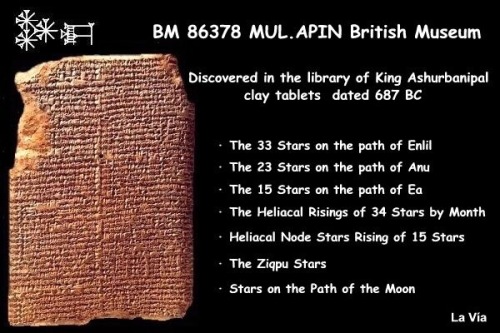

Los sumerios dividían su cielo en tres “caminos” que transcurrían paralelos al ecuador celeste y que daban la vuelta al cielo: el camino de Ea , el camino de Anu y el camino de Enlil . Estos caminos eran las esferas de influencia de tres supradeidades abstractas que jamás se representaban corporalmente: la divina trinidad. Eran las esferas del mundo material (Ea), el mundo humano (Anu) y el mundo divino (Enlil). A través de estas tres bandas serpenteaba “el camino de la Luna” (Charranu), que también era el camino de los planetas: el zodíaco. De esta forma, una parte del zodíaco se encuentra en el camino de Enlil (los signos de verano), una parte en el camino de Anu (signos de primavera y otoño) y una parte en el camino de Ea (los signos de invierno). El mapa estelar adjunto preparado por Werner Papke según el mul.apin muestra esta división para el período de 2340 a.C.

En ese momento de la historia, los sumerios ya conocían el movimiento de desplazamiento precesional de las constelaciones. Las representaciones anteriores siempre hablan de 11 signos zodiacales (todavía falta Libra). En cambio, el mul.apin describe las imágenes de 12 constelaciones y explica claramente que Zibanium (Libra) se construyó a partir de las pinzas del escorpión, para dar al comienzo del otoño su propio signo. Anteriormente, el zodíaco siempre se basaba en dos estrellas: Aldebarán (en Tauro) marcaba el equinoccio (duración del día y de la noche iguales) de primavera y Antares (en Escorpio) determinaba el punto de inicio del otoño. Pero esto sólo es cierto alrededor del 3200 a.C. Probablemente, un poco antes de que se escribiera el mul.apin, se descubrió que el punto de misma duración del día y de la noche se había desplazado hacia el oeste: de Aldebarán a las Pléyades y de Antares hacia las pinzas del escorpión.

http://www.escuelahuber.org/articulos/articulo13.htm

He may also have been aware of MUL.APIN, which was a widely known text both inside and outside the small circle of astronomical scribes (many copies of MUL.APIN were found in archival contexts quite different from the majority of Babylonian astronomical texts). But there is no evidence that Berossos had access to or would have understood contemporary astronomical texts.

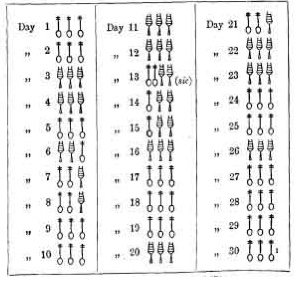

I MUL.APIN sono testi antichi su tavolette di argilla, comprendono un elenco di trentasei stelle, tre stelle per ogni mese dell’anno. Le stelle sono quelle aventi ciascuna la levata eliaca in un particolare mese. Si ha perciò questo schema: nella prima riga sono elencate tre stelle, che hanno la levata eliaca nel primo mese dell’anno, Nīsannu (quello associato all’epoca dell’equinozio di primavera). Nella seconda riga sono elencate altre tre stelle, ancora ciascuna avente levata eliaca nel secondo mese, Ayyāru, e così via.

http://www.lavia.org/italiano/archivio/calendarioakkadit.htm

If he did, he did not include any of this material in the fragments that are preserved to us. Indeed, including such material would probably have had the opposite effect to that which Berossos sought: no-one in the Greek world at the beginning of the third century BC would have been able to understand contemporary Babylonian astronomy, and, being unconcerned with issues of cause, it probably would have been viewed as irrelevant by astronomers in the tradition of Plato and Aristotle.

The transmission and assimilation of contemporary Babylonian astronomy into Greek astronomy could only take place once Greek astronomy itself had turned into a quantitative science in the second century BC. …

The ancient testimonies mentioning Berossos frequently laud him for his astronomical and astrological skill. It is interesting to ask, therefore, how Berossos’s writings were presented and used by later astronomical authors.

First, it is perhaps surprising to note given the popular perception presented in the testimonies that Berossos is not cited or referred to by any of the serious, technical astronomers of the Greco-Roman world: Hipparchus, Geminus, Ptolemy, etc.

Instead, references to Berossos are found only in works of a more general or introductory nature. Indeed, among the authors who cite the so-called astronomical fragments, only Cleomedes is writing a work devoted to astronomy, and his Caelestia is not a high-level work.

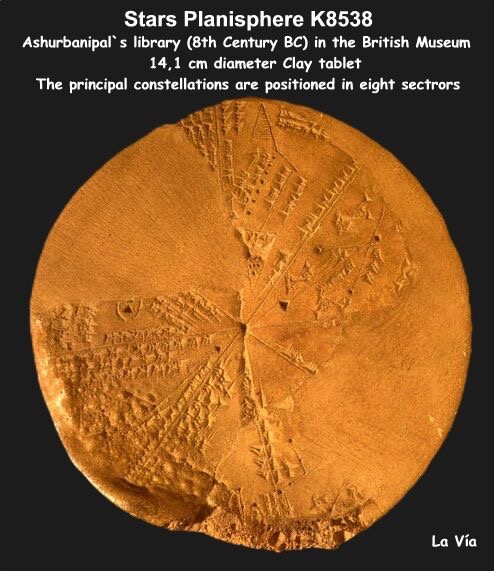

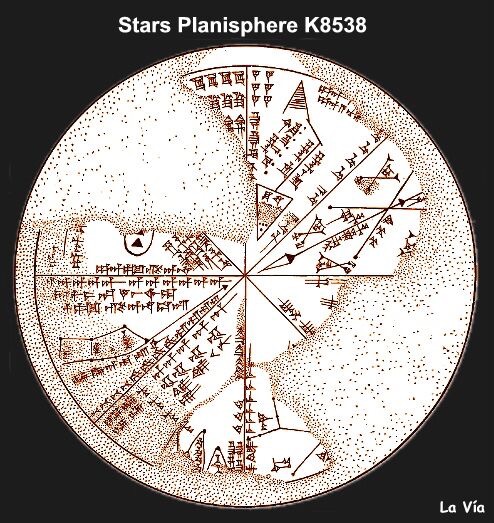

Di seguito possiamo vedere una tavoletta della collezione Kuyunjik, rinvenuta fra le rovine della biblioteca reale di Ashurbanipal (668-627 a.C.) a Ninive, capitale dell’antica Assiria, ed è attualmente esposta al British Museum di Londra (K8538). La scrittura cuneiforme cita chiaramente i nomi di stelle e di pianeti. Insomma la mappa era un planisfero a 360 gradi, ossia la riproduzione di una superficie sferica su un piano dei cieli con al centro la Terra.

http://www.lavia.org/italiano/archivio/calendarioakkadit.htm

The sources of the two main astronomical fragments, Vitruvius and Cleomedes, quote Berossos for his theory of the lunar phases (Cleomedes’ discussion of the moon’s other motions appears as an introduction to this material).

A drawing of British Museum (K8538). As stated above, “La scrittura cuneiforme cita chiaramente i nomi di stelle e di pianeti. Insomma la mappa era un planisfero a 360 gradi, ossia la riproduzione di una superficie sferica su un piano dei cieli con al centro la Terra.”

http://www.lavia.org/italiano/archivio/calendarioakkadit.htm

Interestingly, both these authors present Berossos’ model as one of several explanations for the moon’s phases and then argue against it. Cleomedes presents three models for the lunar phases: Berossos’ model, a model in which the moon is illuminated by reflected sunlight, and a third model, which he will argue is correct, in which the moon is illuminated by a mingling of the sun’s light with the moon’s body.

Cleomedes dismisses Berossos’ model on several grounds:

His doctrine is easily refuted. First, since the Moon exists in the aether, it cannot be ‘half fire’ rather than being completely the same in its substance like the rest of the heavenly bodied.

Second, what happens in an eclipse also conspicuously disconfirms this theory. Berossus, that is, cannot demonstrate how, when the Moon falls into the Earth’s shadow, its light, all of which is facing in our direction at that time, disappears from sight.

If the Moon were constituted as he claims, it would have to become more luminous on falling into the Earth’s shadow rather than disappear from sight!

Vitruvius contrasts Berossos’ model with one he attributes to Aristarchus in which the moon is illuminated by reflected light from the sun. Vitruvius makes it clear that Aristarchus’ model is to be preferred.

Lucretius, presents three models: first the moon is illuminated by reflected sunlight, second the Berossos model (attributed only to ‘the Chaldeans’), and finally the suggestion that the moon is created anew with its own light each day. As is his way, Lucretius does not argue for any one model over the others.

For these later authors, Berossos was useful as a rhetorical tool rather than for the details of his astronomy. So far as we know, no later astronomer in the Greco-Roman world used any of Berossos’s astronomy or attempted to develop it in any way.

Instead, his astronomy provided material that could be argued against in order to promote a different model. If the alternative to the model an author wanted to promote was Berossos’ model, and Berossos’ model was clearly problematical, then this was an implicit argument for the model the author was promoting.

Even though it is not possible to connect each and every chapter (of the Epic of Gilgamesh) with a single star sign, the zodiac does form an excellent backdrop for telling the story.

There are clear references to constellations in the zodiac, as well as to others which are directly next to the zodiac. To illustrate this, (above) is the Babylonian star chart, based on the Mul.Apin tablets, as reconstructed by Gavin White in his book Babylonian Star Lore.

http://thesecretofthezodiac.hu/node/1

Berossos’ astronomy was useful not in itself but for how it could be used as a straw man in arguments for alternative astronomical models. The usefulness of Berossos in this capacity was increased because Berossos had become a well-known name identified with astronomical skill.

Vitruvius, a few chapters after his discussion of the illumination of the moon, lists the inventors of various types of sundial. Berossos is the first name in the list, followed by Aristarchus, Eudoxus, Apollonius and several others (the attributions are certainly fictitious – Vitruvius was an inveterate name-dropper).

If another model was better than Berossos, therefore, the implication is that it must be of the highest quality. Whether or not the astronomical fragments are genuine, which I suspect they largely are, and whether or not Berossos really understood any Babylonian astronomy, which he certainly did not, for later authors he provided a valuable service as an authority figure, imbued both with scientific prestige and a certain eastern exoticism, who could be argued against to promote various astronomical models.”

John M. Steele, “The ‘Astronomical Fragments’ of Berossos in Context,” in Johannes Haubold, Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Robert Rollinger, John Steele (eds.), The World of Berossos, Proceedings of the 4th International Colloquium on the Ancient Near East Between Classical and Ancient Oriental Traditions, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2013, pp. 117-9.