Sacred Prostitution is an Amalgam of Misconceptions

“If prostitution is defined as occurring outside the cultural bounds of controlled sexuality, then controlled coitus within the sacred sphere is not prostitution.

The existence of the so-called sacred marriage ritual during which ritual intercourse seems to have been performed once a year during the New Year’s festival in the latter half of the third millennium and the beginning of the second millennium as symbolic of the union of the divine and human realms does not indicate any ritual promiscuity.

Any cult-related sexual activity simply does not exist outside of sacred marriage rites. Arnaud supposes that the misconception of sacred prostitution arose through the confusion which existed because the lines between sacred sphere and secular sphere were not always kept, and that the temples included underlings of doubtful morality with close ties to groups at the edges of society.

Thus, he maintains that prostitution was a frequent activity without the temple collecting any revenue from it.

In addition to the methodological issues, there are factual inaccuracies abiding in the secondary studies based on dated Assyriological treatments of pertinent information. It is unfortunate that scholars who have been interested in this problem lack access to the original sources. Much confusion has arisen over misunderstood words.

There are two approaches to the question of the existence of sacred prostitution. The first is the argument from silence: there are no legal regulations, administrative documents, or any other record of such a practice. In the absence of positive evidence, the second approach analyzes the negative evidence against sexual activities within the sacred sphere.

Testimony comes from prohibitions and the dire fates which will befall those who commit such transgressions. The words, “if he ate unwittingly what is taboo to his god, if he had intercourse with the priestess of his god . . .,” appear in the confessionals of a penitent sinner.

Sexual offences and the trespassing of sancta are linked in that they are both sins committed against the property of the gods. For the exorcist, there exist diagnostic omens explicating the reasons for the medical predicaments of the patient:

“The embraces given to the entu priestess are discovered by a way of association when a man’s tongue is tied and he cannot speak. Sexual intercourse with a priestess provokes a swollen epigastrium, a feverish abdomen, diseases of the testicles and a scaly penis.”

Thus the issue of sacred prostitution comes down to the accuracy of Herodotus, and much doubt has been cast on his statements. Arnaud has attempted to trace the origins of Herodotus’s statements. He blames the Mesopotamian scribes for misunderstanding their own traditions.

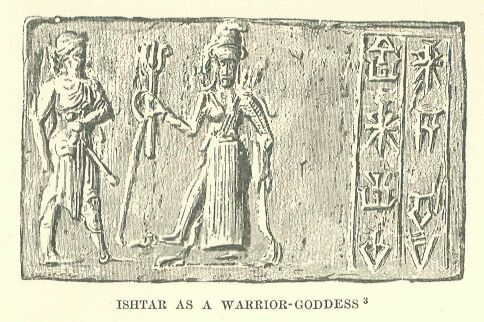

According to Arnaud, those traditions concerned past important cultic functions attributed to women, while the contemporary first-millennium women were relegated to performing household tasks or were prostitutes hanging around the temple precinct, especially in the Aramaized cult of Istar / Inanna of Uruk. The scribes could have speculated upon the debased venal cult, and their speculations could have resulted in the cultic prostitution fiction given to Herodotus.

Thus, this chapter in the annals of historical research, whereby a generalization derived from an ancient fiction coupled with the projection of a modern ideology of women onto historical data becomes fact in scholarly discourse, can now be deleted. “Sacred prostitution” is an amalgam of misconceptions, presuppositions, and inaccuracies.”

Joan Goodnick Westenholz, “Tamar, Qēdēšā, Qadištu, and Sacred Prostitution in Mesopotamia,” The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 82, No. 3 (July, 1989), pp. 262-3.

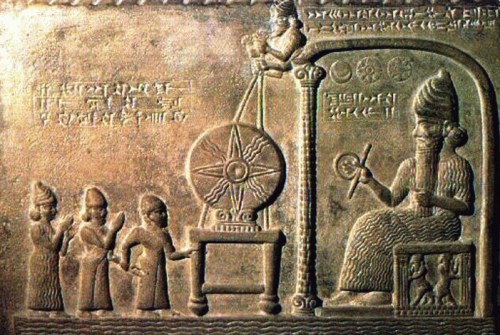

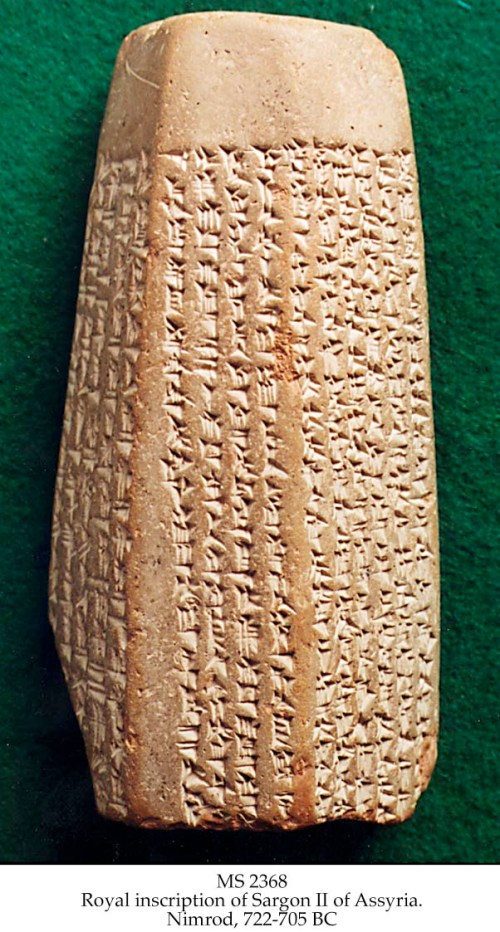

![In 1847 archaeologists discovered a prism of Sargon dated to the early 8th century BC reading: "At the beginning of my royal rule, I…the town of the Samarians I besieged, conquered (2 Lines destroyed) [for the god…] who let me achieve this my triumph… I led away as prisoners [27,290 inhabitants of it (and) equipped from among them (soldiers to man)] 50 chariots for my royal corps…. The town I rebuilt better than it was before and settled therein people from countries which I had conquered. I placed an officer of mine as governor over them and imposed upon them tribute as is customary for Assyrian citizens." (Nimrud Prism IV 25-41) https://theosophical.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg?w=500)