Eco: An Open Classification?

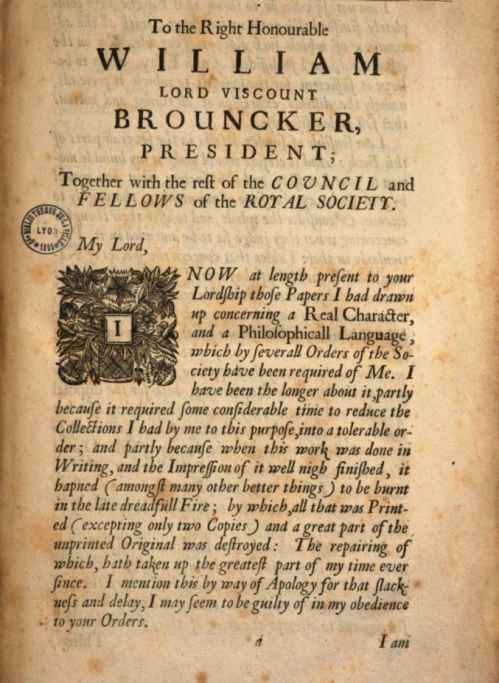

John Wilkins (1614-1672), An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, page a from the Epistle. London, John Martin, 1668. GoogleBooks offers a digital version of the complete text. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“In reality, Wilkins’ classification ought to be regarded as an open one. Following a suggestion of Comenius‘ (in the Via lucis), Wilkins argued that the task of constructing an adequate classification could only be undertaken by a group of scientists working over a considerable period of time, and to this end he solicited the collaboration of the Royal Society.

The Essay was thus considered no more than a first draft, subject to extensive revision. Wilkins never claimed that the system, as he presented it, was finished.

Looking back at figures 12.3 and 12.4, it is evident that there are only nine signs or letters to indicate either differences or species. Does this mean that each genus may have no more than nice species? It seems that the number nine had no ontological significance for Wilkins, and that he chose it simply because he thought nine was the maximum number of entities that might easily be remembered.

He realized that the actual number of species for each genus could not be limited. In fact, certain of the genera in the tables only have six species, but there are ten species for the Umbelliferous and seventeen for the Verticillates Non Fruticose.

To accommodate genera with over nine species Wilkins invented a number of graphic artifices. For simplicity’s sake, let us say that, in the spoken language, to specify a second group of nine species an l is added after the first consonant of the name, and that to specify a third group an r is added.

Therefore if Gαpe is normally Tulip (third species of the fourth difference of the genus Herbs according to their leaves), then Glαpe will be Ramsom, because the addition of the l means that the final e no longer indicates the third species in the genus but the twelfth.

Yet is precisely at this point that we come across a curious error. In the example we just gave, we had to correct Wilkins‘ text (p. 415). The text uses the normal English terms Tulip and Ramsom, but designates them in characters by Gαde and Glαde rather than Gαpe and Glαpe (as it should be).

If one checks carefully on the tables, one discovered that Gαde denotes Barley, not Tulip. Wilkins‘ mistake can be easily explained: regardless of whatever botanical affinities the plants might possess, in common English, the words Tulip and Barley are phonetically dissimilar, and thus unlikely to ever be confused with each other.

In a philosophical language, however, members of the same species are easy to muddle either phonetically or graphically. Without constant double-checking against the tables, it is difficult to avoid misprints and misunderstandings.

The problem is that in a characteristic language, for every unit of an expression one is obliged to find a corresponding content-unit. A characteristic language is thus not founded–as happens with natural languages–on the principle of double articulation, by virtue of which meaningless sounds, or phonemes, are combined to produce meaningful syntagms.

This means that in a language of “real” characters any alteration of a character (or of the corresponding sound) entails a change of sense.

This is a disadvantage that arises from what was intended as the great strength of the system, that is, its criterion of composition by atomic features, in order to ensure a complete isomorphism between expression and content.

Flame is Debα, because here the α designates a species of the element Fire. If we replace the α with an a we obtain a new composition, Deba, that means Comet. When designing his system, Wilkins‘ choice of α and a was arbitrary; once they are inserted into a syntagm, however, the syntagmatic composition is supposed to mirror the very composition of the denoted thing, so that “we should, by learning the Character and the Names of things, be instructed likewise in their Natures” (p. 21).

This creates the problem of how to find the name for yet unknown things. According to Frank (1979: 80), Wilkins‘ language, dominated by the notion of a definitively pre-established Great Chain of Being, cannot be creative. The language can name unknown things, but only within the framework of the system itself.

Naturally, one can modify the tables by inserting into them a new species, but this presupposes the existence of some sort of linguistic authority with the power to permit us to think of a new thing. In Wilkins’s language neologisms are not impossible, but harder to form than in natural languages (Knowlson 1975: 101).

One might defend Wilkins‘ language by arguing that it really encompasses a rational methodology of scientific research. If, for example, we were to transform the character Detα (rainbow) into Denα we would obtain a character that we could analyze as denoting the first species of the ninth difference of the genus Element.

Yet there is no such species in the tables. We cannot take the character metaphorically, because only characters followed by transcendental particles may be so interpreted. We can only conclude that the character unequivocally designates an as yet to be discovered content, and that even if the content remains undiscovered, the character has at least told us the precise point where it is to be found.

But what and where is that “point?” If the tables were analogous to the periodic table in chemistry, then we really would know what to look for. The periodic table contains boxes which, though momentarily empty, might, one day, be filled.

Yet the language of chemistry is rigorously quantitative; the table gives the atomic number and weight of each missing element. An empty space in Wilkins‘ classification, however, merely tells us that there is a hole at that point; it does not tell us what we need to fill it up, or why the hole appears in one space rather than another.

Since Wilkins‘ language is not based on a rigorous classification, it cannot be used as a procedure of scientific discovery.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 248-51.