Nakamura: The Figurines as Magical Objects

The Hybrid

“The magical power of the āšipu also allows him to identify certain mythological and supernatural beings appropriate for the task of protection; these are ancient sages (apkallū), warrior deities and monsters, associated with civilized knowledge and the formidable forces of life, death, peace, and destruction of divine will and rule (Green 1993; Wiggermann 1993).

These figures take on different protective attributes depending on the nature of the represented being; the apkallū act as purifiers and exorcists to expel and ward off evil forces, while monsters, gods, and dogs tend to the defense of the house from demonic intruders (Wiggermann 1992:96–97).

Lahmu, “Hairy,” is a protective and beneficent deity, the first-born son of Apsu and Tiamat. He and his sister Laḫamu are the parents of Anshar and Kishar, the sky father and earth mother, who birthed the gods of the Mesopotamian Pantheon. Laḫmu is depicted as a bearded man with a red sash-usually with three strands- and four to six curls on his head. He is often associated with the Kusarikku or “Bull-Man.” In Sumerian times Laḫmu may have meant “the muddy one”. Lahmu guarded the gates of the Abzu temple of Enki at Eridu. He and his sister Laḫamu are primordial deities in the Babylonian Epic of Creation –Enuma Elis and Lahmu may be related to – or identical with- ‘Lahamu’ one of Tiamat’s Creatures in that epic. http://foundfact.com/portfolio-view/lahmu/#!prettyPhoto http://foundfact.com/library/beings-people-and-gods/page/6/#!prettyPhoto

All of these figures find some association either with the underworld or the freshwater ocean under the earth (apsû) which was the domain of Enki, the god associated with wisdom, magic, incantation, and the arts and crafts of civilization (Black and Green 1992:75), and notably, all but the lahmu portray composite human–animal physiognomies (Figure 2.2).

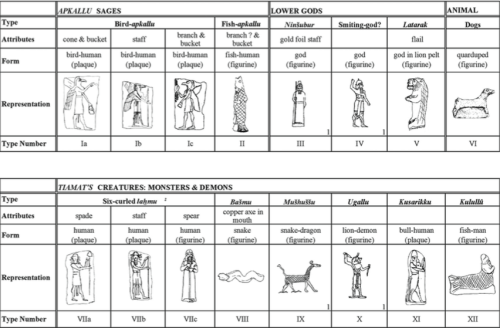

Figure 2.2. Apotropaic figures with associated features.

1. Drawing after Richards in Black and Green (1992:65).

2. The identification of the lahmu figure is controversial; it names both a cosmogonic deity and one of Tiamat’s creatures (Wiggermann 1992:155–156), and may also represent an apkallu sage (Ellis 1995:165; Russell 1991:184, fn. 27)

Such forms manifest a communion of things generally held to be opposed to each other. The blending of humans and animals in this context might capitalize on the tension between Mesopotamian conceptions of a structured, civilized human world and a chaotic, untamed natural world (Bottéro 1992).

Hybrids materialize a unity of self and other, human and animal as a strange being that is at once knowable and controllable and unknowable and incontrollable.

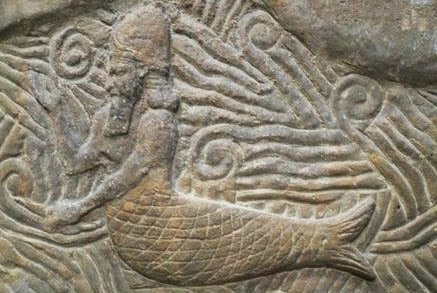

Fish-man known as a Kulullû. Terracotta figurine (8th-7th BCE) in the Louvre collection, Nr. 3337.

The Kulullû is distinct from the fish-Apkallū. They are not the same.

As beings in-between, hybrids embody potential, transition, and similarity in difference. Such liminality is often associated with dangerous power, a power that obeys the apotropaic economy of the supplement, since it terrifies and yet provides the surest protection against that terror (Derrida 1974:154).

By miming such beings in clay figurines, the āšipu brings forth their active life and force in petrified form. Capitalizing on the apotropaic logic of defense, this gesture captures self-defeating force and suspends it in space, material, and time.

Many of the figurine types are depicted in movement with hands gesturing and a foot forward to suggest forward movement. Following Susan Stewart (1984:54), I submit that the force of animated life does not diminish when arrested in the fixity and exteriority of the figurine, but rather, is captured as a moment of hesitation always on the verge of forceful action.

The apotropaic figurine is a magical object — what Michael Taussig calls a “time–space compaction of the mimetic process” — doubled over since its form and matter, creation and presentation capture certain inherent energies that humans desire to control.

The magical object, which encounters the unknown by presenting its form and image “releases a force capable of vanquishing it, or even befriending it” (Deleuze 2003:52). But as ritual texts and archaeological deposits confirm, it was not just the images themselves that rendered power, but something in the process of their creation.

While such apotropaic figures appear in grand scale and idealized form on wall reliefs flanking entrances of kingly palaces purifying all who passed through the gates, the figures standing guard in floor deposits performed an additional task.”

Carolyn Nakamura, “Mastering matters: magical sense and apotropaic figurine worlds of Neo-Assyria,” Archaeologies of materiality (2005): 34-6.

![Illustration: Shamash the Sun-god rising on the horizon, flames of fire ascending from his shoulder. The two portals of the dawn, each surmounted by a lion, are being drawn open by attendant gods. From a Babylonian seal cylinder in the British Museum. [No. 89,110.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00323246_001_l.jpg?w=500)