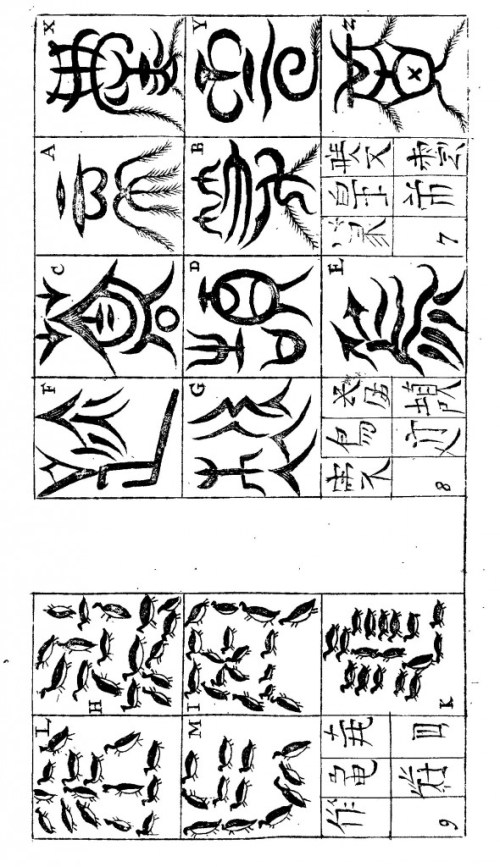

Eco: The Egyptian vs. The Chinese Way, 2

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), origins of the Chinese characters, China Illustrata, 1667, p. 229, courtesy of Stanford University. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“On the subject of signatures, Della Porta said that spotted plants which imitated the spots of animals also shared their virtues (Phytognomonica, 1583, III, 6): the bark of a birch tree, for example, imitated the plumage of a starling and is therefore good against impetigo, while plants that have snake-like scales protect against reptiles (III, 7).

Thus in one case, morphological similarity is a sign for alliance between a plant and an animal, while in the next it is a sign for hostility.

Taddeus Hageck (Metoscopicorum libellus unus, 1584: 20) praises among the plants that cure lung diseases two types of lichen: however, one bears the form of a healthy lung, while the other bears the stained and shaggy shape of an ulcerated one.

The fact that another plant is covered with little holes is enough to suggest that this plant is capable of opening the pores. We are thus witnessing three very distinct principles of relation by similarity: resemblance to a healthy organ, resemblance to a diseased organ, and an analogy between the form of a plant and the therapeutic result that it supposedly produced.

This indifference as to the nature of the connection between signatures and signatum holds in the arts of memory as well. In his Thesaurus atificiosae memoriae (1579), Cosma Roselli endeavored to explain how, once of a system of loci and images had been established, it might actually function to recall the res memoranda.

He thought it necessary to explain “quomodo multis modis, aliqua res alteri sit similis” (Thesaurus, 107), how, that is, one thing could be similar to another. In the ninth chapter of the second part he tried to construct systematically a set of criteria whereby images might correspond to things:

“according to similarity, which, in its turn, can be divided into similarity of substance (such as man as the microcosmic image of the macrocosm), similarity in quantity (the ten fingers for the Ten Commandments), according to metonymy or antonomasia (Atlas for astronomers or for astronomy, a bear for a wrathful man, a lion for pride, Cicero for rhetoric):

by homonyms: a real dog for the dog constellation;

by irony and opposition: the fatuous for the wise;

by trace: the footprint for the wolf, the mirror in which Titus admired himself for Titus;

by the name differently pronounced: sanum for sane;

by similarity of name: Arista [awn] for Aristotle;

by genus and species: leopard for animal;

by pagan symbol: the eagle for Jove;

by peoples: Parthians for arrows, Scythians for horses, Phoenicians for the alphabet;

by signs of the zodiac: the sign for the constellation;

by the relation between organ and function;

by common accident: the crow for Ethiopia;

by hieroglyph: the ant for providence.”

The Idea del teatro by Giulio Camillo (1550) has been interpreted as a project for a perfect mechanism for the generation of rhetorical sentences.

Yet Camillo speaks casually of similarity by morphological traits (a centaur for a horse), by action (two serpents in combat for the art of war), by mythological contiguity (Vulcan for the art of fire), by causation (silk worms for couture), by effects (Marsyas with his skin flayed off for butchery), by relation of ruler to ruled (Neptune for navigation), by relation between agent and action (Paris for civil courts), by antonomasia (Prometheus for man the maker), by iconism (Hercules drawing his bow towards the heavens for the sciences regarding celestial matters), by inference (Mercury with a cock for bargaining).

It is plain to see that these are all rhetorical connections, and there is nothing more conventional that a rhetorical figure. Neither the arts of memory nor the doctrine of signatures is dealing, in any degree whatsoever, with a “natural” language of images.

Yet a mere appearance of naturalness has always fascinated those who searched for a perfect language of images.

The study of gesture as the vehicle of interaction with exotic people, united with a belief in a universal language of images, could hardly fail to influence the large number of studies which begin to appear in the seventeenth century on the education of deaf-mutes (cf. Salmon 1972: 68-71).

In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet wrote a Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar los mudos. Fifteen years later, Mersenne (Harmonie, 2) connected this question to that of a universal language. John Bulwer suggested (Chirologia, 1644) that only by a gestural language can one escape from the confusion of Babel, because it was the first language of humanity.

Dalgarno (see ch. 11) assured his reader that his project would provide an easy means of educating deaf-mutes, and he again took up this argument in his Didascalocophus (1680). In 1662, the Royal Society devoted several debates to Wallis’s proposals on the same topic.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 171-3.