Eco: Theoretical Objections and Counter-objections

![Projet_d'éléments_d'idéologie_par_le_[...]Destutt_de_bpt6k10455061](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/projet_dc3a9lc3a9ments_didc3a9ologie_par_le_-destutt_de_bpt6k10455061.jpeg?w=500)

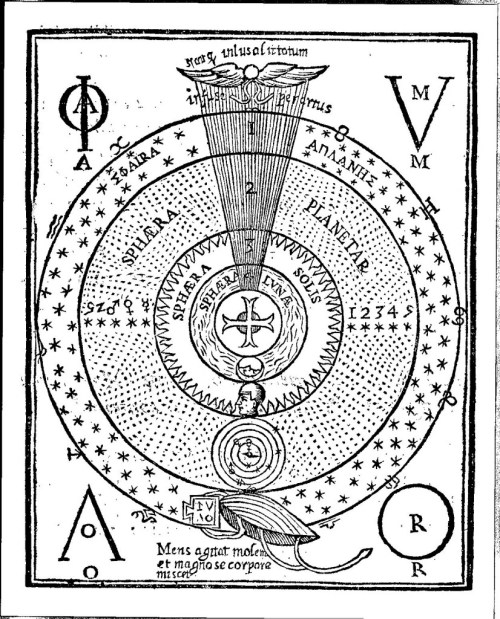

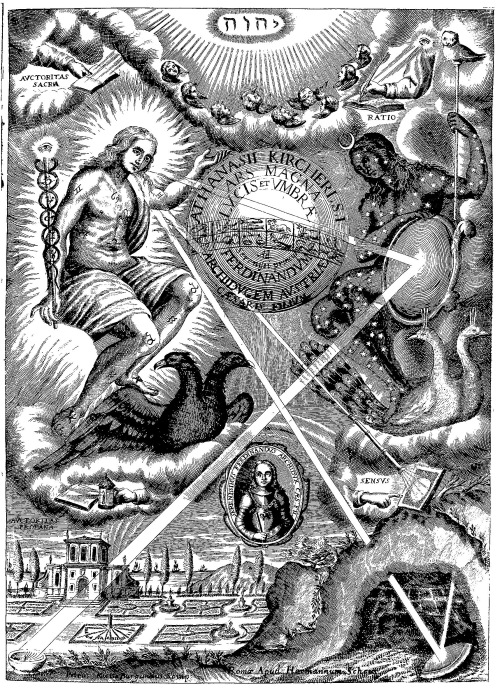

Antoine-Louis-Claude Destutt de Tracy (1754-1836), Projet d’éléments d’idéologie, Paris, 1801. This copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“A fundamental objection that can be applied to any of the a posteriori projects generically is that they can make no claim to having identified and artificially reorganized a content system.

They simply provide an expression system which aims at being easy and flexible enough to express the contents normally expressed in a natural language. Such a practical advantage is also a theoretical limit. If the a priori languages were too philosophical, their a posteriori successors are not philosophical enough.

The supporters of an IAL have neither paid attention to the problem of linguistic relativism, nor ever been worried by the fact that different languages present the world in different ways, sometimes mutually incommensurable.

They have usually taken it for granted that synonymous expressions exist from language to language, and the vast collection of books that have been translated into Esperanto from various of the world’s languages is taken as proof of the complete “effability” of this language (this point has been discussed, from opposite points of view, by two authors who are both traditionally considered as relativist, that is, Sapir and Whorf—cf. Pellerey 1993: 7).

To accept the idea that there is a content system which is the same for all languages means, fatally, to take surreptitiously for granted that such a model is the western one. Even if it tries to distance itself in certain aspects from the Indo-European model, Esperanto, both in its lexicon and in its syntax, remains basically an Indo-European tongue.

As Martinet observed, “the situation would have been different if the language had been invented by a Japanese” (1991: 681).

One is free to regard all these objections as irrelevant. A theoretical weak point may even turn out to be a practical advantage. One can hold that linguistic unification must, in practice, accept the use of the Indo-European languages as the linguistic model (cf. Carnap in Schlipp 1963:71).

It is a view that seems to be confirmed by actual events; for the moment (at least) the economic and technological growth of Japan is based on Japanese acceptance of an Indo-European language (English) as a common vehicle.

Both natural tongues and some “vehicular” languages have succeeded in becoming dominant in a given country or in a larger area mainly for extra-linguistic reasons. As far as the linguistic reasons are concerned (easiness, economy, rationality and so on), there are so many variables that there are no “scientific” criteria whereby we might confute the claim of Goropius Becanus that sixteenth century Flemish was the easiest, most natural, sweetest and most expressive language in the entire universe.

The predominate position currently enjoyed by English is a historical contingency arising from the mercantile and colonial expansion of the British Empire, which was followed by American economic and technological hegemony.

Of course, it may also be maintained that English has succeeded because it is rich in monosyllables, capable of absorbing foreign words and flexible in forming neologisms, etc.: yet had Hitler won World War II and had the USA been reduced to a confederation of banana republics, we would probably today use German as a universal vehicular language, and Japanese electronics firms would advertise their products in Hong Kong airport duty-free shops (Zollfreie Waren) in German.

Besides, on the arguable rationality of English, and of any other vehicular language, see the criticism of Sapir (1931).

There is no reason why an artificial language like Esperanto might not function as an international language, just as certain natural languages (such as Greek, Latin, French, English, Swahili) have in different historical periods.

We have already encountered in Destutt de Tracy an extremely powerful objection: a universal language, like perpetual motion, is impossible for a very “peremptory” reason: “Even were everybody on earth to agree to speak the same language from today onwards, they would rapidly discover that, under the influence of their own use, the single language had begun to change, to modify itself in thousands of different ways in each different country, until it produced in each a different dialect which gradually grew away from all the others” (Eléments d’idéologie, II, 6, 569).

It is true that, just for the above reasons, the Portuguese of Brazil today differs from the Portuguese spoken in Portugal so much that Brazilian and Portuguese publishers publish two different translations of the same foreign book, and it is a common occurrence for foreigners who have learned their Portuguese in Rio to have difficulty understanding what they hear on the streets of Lisbon.

Against this, however, one can point out the Brazilians and Portuguese still manage to understand each other well enough in practical, everyday matters. In part, this is because the mass media help the speakers of each variety to follow the transformations taking place on the other shore.

Supporters of Esperanto like Martinet (1991: 685) argue that it would be, to say the least, naive to to suppose that, as an IAL diffused into new areas, it would be exempt from the process through which languages evolve and split up into varieties of dialects.

Yet in so far as an IAL remained an auxiliary language, rather than the primary language of everyday exchange, the risks of such a parallel evolution would be diminished.

The action of the media, which might reflect the decisions of a sort of international supervisory association, could also contribute to the establishment and maintenance of standards, or, at least, to keeping evolution under control.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 330-2.