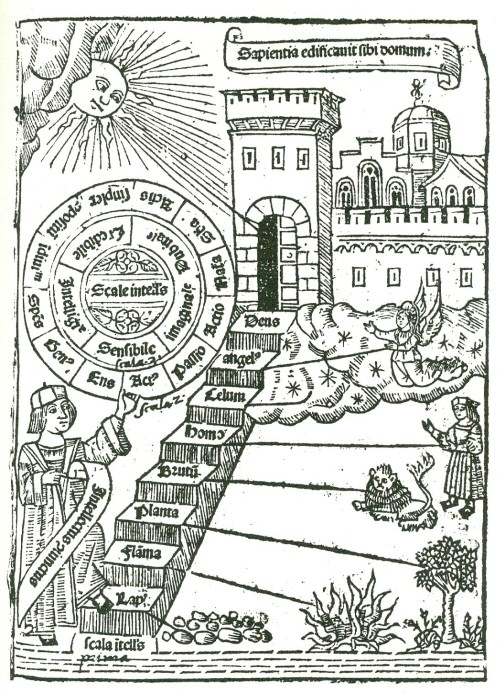

Eco: The Arbor Scientarium

Ramon Llull, Liber de ascensu et decensu intellectus, 1304, first published 1512. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“The Lullian art was destined to seduce later generations who imagined that they had found in it a mechanism to explore the numberless possible connections between dignities and principles, principles and questions, questions and virtues or vices.

Why not even construct a blasphemous combination stating that goodness implies an evil God, or eternity a different envy? Such a free and uncontrolled working of combinations and permutations would be able to produce any theology whatsoever.

Yet the principles of faith, and the belief in a well-ordered cosmos, demanded that such forms of combinatorial incontinence be kept repressed.

Lull’s logic is a logic of first, rather than second, intentions; that is, it is a logic of our immediate apprehension of things rather than of our conceptions of them. Lull repeats in various places that if metaphysics considers things as they exist outside our minds, and if logic treats them in their mental being, the art can treat them from both points of view.

Consequently, the art could lead to more secure conclusions than logic alone, “and for this reason the artist of this art can learn more in a month than a logician can in a year.” (Ars magna, X, 101).

What this audacious claim reveals, however, is that, contrary to what some later supposed, Lull’s art is not really a formal method.

The art must reflect the natural movement of reality; it is therefore based on a notion of truth that is neither defined in the terms of the art itself, nor derived from it logically. It must be a conception that simply reflects things as they actually are.

Lull was a realist, believing in the existence of universals outside the mind. Not only did he accept the real existence of genera and species, he believed in the objective existence of accidental forms as well.

Thus Lull could manipulate not only genera and species, but also virtues, vices and every other sort of differentia as well; at the same time, however, all those substances and accidents could not be freely combined because their connections were determined by a rigid hierarchy of beings (cf. Rossi 1960: 68).

In his Dissertatio de arte combinatoria of 1666, Leibniz wondered why Lull had limited himself to a restricted number of elements. In many of his works, Lull had, in truth, also proposed systems based on 10, 16, 12 or 20 elements, finally settling on 9. But the real question ought to be not why Lull fixed upon this or that number, but why the number of elements should be fixed at all.

In respect of Lull’s own intentions, however, the question is beside the point; Lull never considered his to be an art where the combination of the elements of expression was free rather than precisely bound in content.

Had it not been so, the art would not have appeared to Lull as a perfect language, capable of illustrating a divine reality which he assumed from the outset as self-evident and revealed.

The art was the instrument to convert the infidels, and Lull had devoted years to the study of the doctrines of the Jews and Arabs. In his Compendium artis demonstrativa (“De fine hujus libri“) Lull was quite explicit: he had borrowed his terms from the Arabs.

Lull was searching for a set of elementary and primary notions that Christians held in common with the infidels. This explains, incidentally, why the number of absolute principles is reduced to nine (the tenth principle, the missing letter A, being excluded from the system, as it represented perfection or divine unity).

One is tempted to see in Lull’s series the ten Sefirot of the kabbala, but Plazteck observes (1953-4: 583) that a similar list of dignities is to be found in the Koran. Yates (1960) identified the thought of John Scot Erigene as a direct source, but Lull might have discovered analogous lists in various other medieval Neo-Platonic texts–the commentaries of pseudo-Dionysius, the Augustinian tradition, or the medieval doctrine of the transcendental properties of being (cf. Eco 1956).

The elements of the art are nine (plus one) because Lull thought that the transcendental entities recognized by every monotheistic theology were ten.

Lull took these elementary principles and inserted them into a system which was already closed and defined, a system, in fact, which was rigidly hierarchical–the system of the Tree of Science.

To put this in other terms, according to the rules of Aristotelian logic, the syllogism “all flowers are vegetables, X is a flower, therefore X is a vegetable” is valid as a piece of formal reasoning independent of the actual nature of X.

For Lull, it mattered very much whether X was a rose or a horse. If X were a horse, the argument must be rejected, since it is not true that a horse is a vegetable. The example is perhaps a bit crude; nevertheless, it captures very well the idea of the great chain of being (cf. Lovejoy 1936) upon which Lull based his Arbor scientiae (1296).”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 64-7.