The Gods Fear Zu

“A long but broken text explains why it was that he had to take refuge in the mountain of ‘Sabu under the guise of a bird of prey.

We learn that Zu gazed upon the work and duties of Mul-lil;

“he sees the crown of his majesty, the clothing of his divinity, the tablets of destiny, and Zu himself, and he sees also the father of the gods, the bond of heaven and earth.

The desire to be Bel (Mul-lil) is taken in his heart; yea, he sees the father of the gods, the bond of heaven and earth; the desire to be Bel is taken in his heart:

‘Let me seize the tablets of destiny of the gods, and the laws of all the gods let me establish (lukhmum); let my throne be set up, let me seize the oracles; let me urge on the whole of all of them, even the spirits of heaven.’

So his heart devised opposition; at the entrance to the forest where he was gazing he waited with his head (intent) during the day.

When Bel pours out the pure waters, his crown was placed on the throne, stripped from (his head). The tablets of destiny (Zu) seized with his hand; the attributes of Bel he took; he delivered the oracles.

(Then) Zu fled away and sought his mountains. He raised a tempest, making (a storm).”

Then Mul-lil, “the father and councillor” of the gods, consulted his brother divinities, going round to each in turn. Anu was the first to speak. He

“opened his mouth, he speaks, he says to the gods his sons: ‘(Whoever will,) let him subjugate Zu, and (among all) men let the destroyer pursue him (?).

(To Rimmon) the first-born, the strong, Anu declares (his) command, even to him: …’0 Rimmon, protector (?), may thy power of fighting never fail! (Slay) Zu with thy weapon. (May thy name) be magnified in the assembly of the great gods. (Among) the gods thy brethren (may it destroy) the rival. May incense (?) (etarsi) be offered, and may shrines be built!

(In) the four (zones) may they establish thy strongholds. May they magnify thy fortress that it become a fane of power in the presence of the gods, and may thy name be mighty?’

(Rimmon) answered the command, (to Anu) his father he utters the word:

‘(0 my father, to a mountain) none has seen mayest thou assign (him); (never may) Zu play the thief (again) among the gods thy sons; (the tablets of destiny) his hand has taken; (the attributes of Bel) he seized, he delivered the oracles; (Zu) has fled away and has sought his mountains.'”

Rimmon goes on to decline the task, which is accordingly laid upon another god, but with like result.

George Rawlinson: Seven Great Monarchies Of The Ancient Eastern World, Vol 1. (1875)

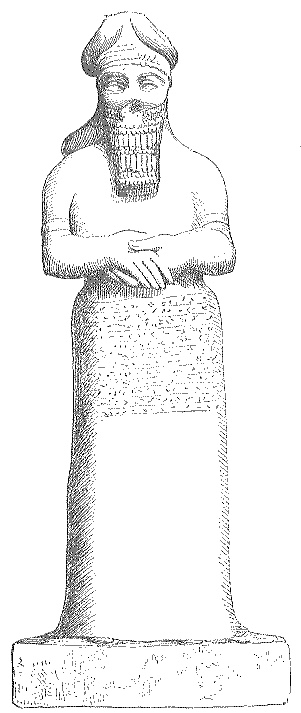

The Chaldean god Nebo, from a statue in the British Museum.

http://www.totallyfreeimages.com/56/Nebo.

Then Anu turns to Nebo:

“(To Nebo), the strong one, the eldest son of Istar, (Anu declares his will) and addresses him: … ‘0 Nebo, protector (?), never may thy power of fighting fail! (Slay) Zu with thy weapon. May (thy name) be magnified in the assembly of the great gods! Among the gods thy brethren (may it destroy) the rival!

May incense (?) be offered and may shrines be built! In the four zones may thy strongholds be established! May they magnify thy stronghold that it become a fane of power in the presence of the gods, and may thy name be mighty!’

Nebo answered the command: ‘0 my father, to a mountain none hast seen mayest thou assign (him); never may Zu play the thief (again) among the gods thy sons! The tablets of destiny his hand has taken; the attributes of Bel he has seized; he has delivered the oracles; Zu is fled away and (has sought) his mountains.'”

Like Rimmon, Nebo also refused to hunt down and slay his brother god, the consequence being, as we have seen, that Zu escaped with his life, but was changed into a bird, and had to live an exile from heaven for the rest of time.”

A.H. Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians, 5th ed., London, 1898, pp. 297-9.

September 6, 2015

Kvanvig: Five Specialties of Sages Communicating with the Divine

“There is no doubt that these assertions by the kings are tendentious; and one can discuss how wise the kings in reality were. They needed high competence in practical affairs; this is a matter of fact. They administered empires, warfare, economy, building of temples, palaces; this is not done without a high degree of skill.

(Cf. R.F.G. Sweet, “The Sage in Mesopotamian Palaces and Royal Courts,” in J.G. Gammie and L.G. Perdue, eds., The Sage in Israel and the Ancient Near East, Winona Lake, 1990, pp. 99-107, 99f.)

Nevertheless, the kings boast of knowledge of a higher order, a knowledge that shares in the divine wisdom, either represented through the gods themselves, or through the apkallus. This at least included knowledge about reading and writing.

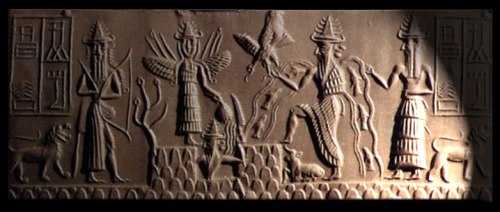

(Click to zoom in).

A king depicted with the sacred tree and his ummanu standing behind him with mullilu cone and banduddu bucket.

Some analysts consider the cone blessing gesture to be fertilization or pollination of the stylized date palm.

It is interesting to note that the depictions of the king mirror one another, but with differences.

In both, symbols of sovereignty are grasped in their left hands. A scepter or mace, in either case. The other hand, the right hand, plucks or blesses the tree.

The winged conveyance hovers above the tree. Note that the kings wear indistinct caps, while the ummanus wear horned crowns indicative of divinity. Also, the ummanu have wings.

From the Northwest palace at Nimrud. Held in the collection of the British Museum, BM 6657.

As far as we know, only three kings claim to have been literate in two thousand years of Mesopotamian history: Šulgi, Lipit-Ištar, and Ashurbanipal.

(Sweet, “The Sage in Akkadian Literature,” p. 65.)

The kings claimed obviously to share in this higher degree of wisdom, not only because of personal reasons, but because of the royal ideology according to which they ruled.

The wisdom they needed was not only insight into how to rule a country, but insight into the divine realm, to read the signs of the gods, to appease the gods when necessary, and to secure divine assistance to conquer demonic attacks.

To secure this kind of wisdom the king associated with a body of experts professionalized in various fields of this higher form of wisdom that demanded communication with the divine. This is the ideology of the pairing of kings and sages / scholars in Berossos and more extensively in the Uruk tablet.

In order to rule, a king needed a scholar at his side. In a chronographic composition from about 640 BCE, listing the kings of Assyria and Babylon together, the kings are listed together with one or two ummanus.

(Cf. S. Parpola, Letters from Assyrian Scholars to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. Part II: Commentary and Appendices, vol. 5/2, AOAT, Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1983, pp. 448-9.)

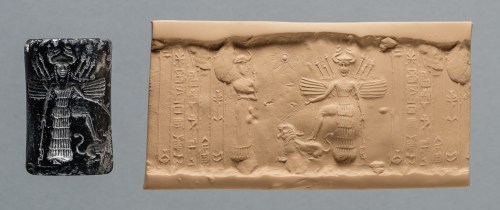

An ummanu. In this case, the ummanu wears a headband with a rosette, rather than the usual horned tiara indicative of divinity, or semi-divinity. This must be an apkallu, an umu-apkallu, as it has wings, an indicator of supernatural status.

Here we are in the historical reality lying behind the imagination of parallel kings and apkallus in antediluvian time. Historically, there existed ummanus of such a high rank that they were included in a list of rulers.

Due to the finding of numerous letters from the Assyrian royal court between the kings and these experts, we have gained profound insight into the duties of the experts. S. Parpola, who edited the letters, found that there are five special fields of expertise:

Based on this correspondence, Parpola found that the experts could be divided into two groups, forming an “inner” and an “outer” circle in relation to the king.

During the reign of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal there were 16 men forming the “inner circle.” They were quite generally designated with the title rab, “chief:” rab tupšarrī, rab bārê, rab āšipī, etc.

An umu-apkallu at far left, with horned tiara indicative of divinity. The mullilu cone and banduddu bucket are in their customary places, rosette bracelets are displayed, and this ummanu is winged.

This frieze is unusual for the fine detail lavished on the fringe and tassels of the garments. The sandals are portrayed with uncommon precision.

On the right side, an ambiguous figure, perhaps a lesser order of ummanu, a specialist sage in service to the king. Beardless, the figure could be a eunuch, raising a royal mace or scepter surmounted with a rosette in its right hand. Could this be a woman at court? The facial characteristics are intriguing, the figure appears to wear a long fringed skirt rather than the robe portrayed on the apkallu at left, and appears to bear both a sword and a bow with a quiver of arrows. Perhaps this is the arms bearer of the king, holding the royal scepter for his convenience.

From the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, in the collection of the British Museum.

BM 6642.

The examination of their names and position demonstrated that they were high ranking men, and that only these few select “wise men” could be engaged in any sort of “regular” correspondence with the king.

Among the members of the “inner circle” there were several instances of family ties, giving the impression that these important court offices of scholarly advisors were in the hand of a few privileged families, “a veritable scholarly “mafia,” which monopolized these offices from generation to generation.”

The men of the “inner circle” did not reside in the palace area but in their own houses situated in downtown Nineveh. Occasionally they could leave their houses for visits to the palace and the king.”

Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011, pp. 141-3.

Share this: