Eco: The Indo-European Hypothesis, 2

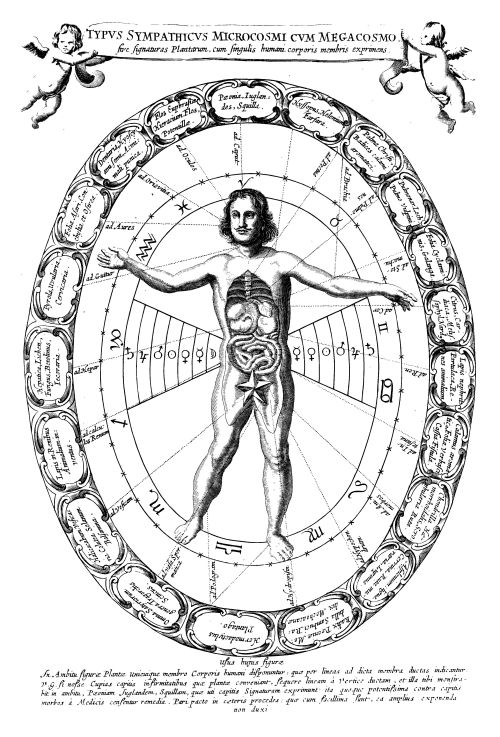

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), sympathies between the microcosm and the megacosm, from Mundus subterraneus, 1665, vol. 2, p.406. Courtesy of Stanford University and the University of Oklahoma Libraries. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“But are we really able to say that with the birth of the modern science of linguistics the ghost of Hebrew as the holy language had finally been laid to rest? Unfortunately not. The ghost simply reconstituted itself into a different, and wholly disturbing, Other.

As Olender (1989, 1993) has described it, during the nineteenth century, one myth died only to be replaced by another.

With the demise of the myth of linguistic primacy, there arose the myth of the primacy of a culture–or of a race. When the Hebrew language and civilization was torn down, the myth of the Aryan races rose up to take its place.

The reality of Indo-European was only virtual; yet it was still intrusive. Placed face to face with such a reality, Hebrew receded to the level of metahistory. It became a symbol.

At the symbolic level, Hebrew ranged from the linguistic pluralism of Herder, who celebrated it as a language that was fundamentally poetic (thus opposing an intuitive to a rationalistic culture), to the ambiguous apology of Renan, who–by contrasting Hebrew as the tongue of monotheism and of the desert to Indo-European languages (with their polytheistic vocation)–ends up with oppositions which, without our sense of hindsight, might even seem comic: the Semitic languages are incapable of thinking in terms of multiplicity, are unwilling to countenance abstraction; for this reason the Semitic culture would remain closed to scientific thinking and devoid of a sense of humor.

Unfortunately, this is not just a story of the gullibility of scientists. We know only too well that the Aryan myth had political consequences that were profoundly tragic. I have no wish to saddle the honest students of Indo-European with blame for the extermination camps, especially as–at the level of linguistic science–they were right.

It is rather that, throughout this book, we have been sensitive to side effects. And it is hard not to think of these side effects when we read in Olender the following passage from the great linguist, Adolphe Pictet, singing this hymn to Aryan culture:

“In an epoch prior to that of any historical witnesses, an epoch lost in the night of time, a race, destined by providence to one day rule the entire world, slowly grew in its primitive birthplace, a prelude to its brilliant future.

Privileged over all others by the beauty of their blood, by their gifts of intelligence, in the bosom of a great and severe nature that would not easily yield up its treasures, this race was summoned from the very beginning to conquer. [ . . . ]

Is it not perhaps curious to see the Aryas of Europe, after a separation of four or five thousand years, close the circle once again, reach their unknown brothers in India, dominate them, bring to them the elements of a superior civilization, and then to find ancient evidence of a common origin?”

(Les origines indo-européennes ou les Aryas primitifs, 1859-63: III, 537, cited in Olender 1989: 130-9).

At the end of a thousand year long ideal voyage to the East in search of roots, Europe had at last found some ideal reasons to turn that virtual voyage into a real one–for the purposes not of intellectual discovery, however, but of conquest.

It was the idea of the “white man’s burden.” With that, there was no longer any need to discover a perfect language to convert old or new brothers. It was enough to convince them to speak an Indo-European language, in the name of a common origin.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 105-6.