Eco: Cosmic Permutability and the Kabbala of Names, 2

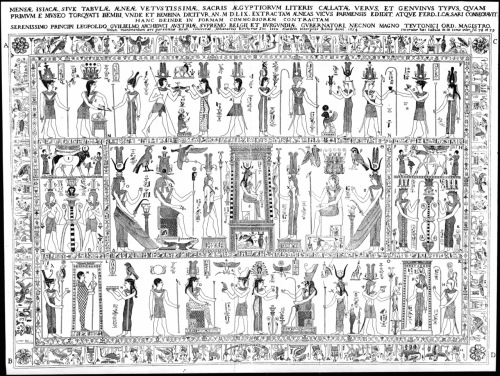

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), The Bembine Table of Isis, Oedipus Aegypticiacus, or Mensa Isiaca, N. Inv. C. 7155, Museo Egizio, photo by Fuzzypeg from Manly Palmer Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages (1928), all rights released. The Bembine Table was acquired by Cardinal Bembo after the sack of Rome in 1527, then purchased by the Savoy King Carlo Emanuele I in 1630 in Turin. A Roman interpretation of a bronze and silver altar table in an Egyptian style, early scholars surmised that the table pertained to an Isis cult. Kircher relied upon it for the third volume of his masterwork. It was ultimately determined to be an antique forgery, and not a work of ancient Egypt. This image is in the public domain. The author died over 70 years ago.

“What justified this process of textual dissolution was that, for Abulafia, each letter, each atomic element, already had a meaning of its own, independent of the meaning of the syntagms in which it occurred.

Each letter was already a divine name: “Since, in the letters of the Name, each letter is already a Name itself, know that Yod is a name, and YH is a name” (Perush Havdalah de-Rabbi ‘Akivà).

This practice of reading by permutation tended to produce ecstatic effects:

“And begin by combining this name, namely, YHWH, at the beginning alone, and examining all its combinations and move it, turn it about like a wheel, returning around, front and back, like a scroll, and do not let it rest, but when you see its matter strengthened because of the great motion, because of the fear of confusion of your imagination, and rolling about of your thoughts, and when you let it rest, return to it and ask [it] until there shall come to your hand a word of wisdom from it, do not abandon it.

Afterwards go on to the second one from it, Adonay, and ask of it its foundation [yesodo] and it will reveal to you its secret [sodo]. And then you will apprehend its matter in the truth of its language. Then join and combine the two of them [YHWH and Adonay] and study them and ask them, and they will reveal to you the secrets of wisdom . . .

Afterwards combine Elohim, and it will also grant you wisdom, and then combine the four of them, and find the miracles of the Perfect One [i.e. God], which are miracles of wisdom.” (Hayyê ha-Nefes, in Idel 1988c:21).

If we add that the recitation of the names was accompanied by special techniques of breathing, we begin to see how from recitation the adept might pass into ecstasy, and from ecstasy to the acquisition of magic powers; for the letters that the mystic combined were the same sounds with which God created the world.

This latter aspect came especially into prominence during the fifteenth century. For Yohanan Alemanno, friend and inspirer of Pico della Mirandola, “the symbolic cargo of language was transformed into a kind of quasi-mathematical command. Kabbalistic symbolism thus turned into–or perhaps returned to–a magical language of incantation” (Idel 1988b: 204-5).

For the ecstatic kabbala, language was a self-contained universe in which the structure of language represented the structure of reality itself. Already in the writings of Philo of Alexandria there had been an attempt to compare the intimate essence of the Torah with the Logos as the world of ideas.

Such Platonic conceptions had even penetrated into the Haggidic and Midrashic literature in which the Torah was conceived as providing the scheme according to which God created the world.

The eternal Torah was identified with wisdom and, in many passages, with the world of forms or universe of archetypes. In the thirteenth century, taking up a decidedly Averroist line, Abulafia equated the Torah with the active intellect, “the form of all the forms of separate intellects” (Sefer Mafteakh ha-Tokhahot).

In contrast, therefore, with the main philosophical tradition (from Aristotle to the Stoics and to the Middle Ages, as well as to Arab and Judaic philosophers), language, in the kabbala, did not represent the world merely by referring to it.

It did not, that is, stand to the world in the relation of signifier to signified or sign to its referent. If God created the world by uttering sounds or by combining written letters, it must follow that these semiotic elements were not representations of pre-existing things, but the very forms by which the elements of the universe are moulded.

The significance of this argument in our own story must be plain: the language of creation was perfect not because it merely happened to reflect the structure of the universe in some exemplary fashion; it created the universe.

Consequently it stands to the universe as the cast stands to the object cast from it.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 30-2.