“–banduddû, “bucket”.

Banduddû unquestionably denotes the bucket held by many figures of the reliefs, cf. Frank LSS III/3 671, Zimmern ZA 35 151, Smith JRAS 1926 70913, Hrouda Kulturgeschichte 77, Madhloom Chronology 109ff., Kolbe Reliefprogramme Type IIA, VI, IIB, IIC.

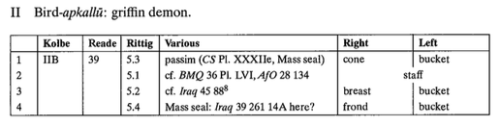

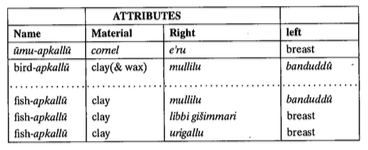

The object is attested also in the hands of clay figures: Rittig Kleinplastik 70ff. (bird-apkallu), 80ff. (fish-apkallu), 98f. (kusarikku). Two buckets from Babylon belonged to unknown figures of wood. The actual figures always carry the bucket with their left hand; the texts prescribe the banduddû for the left hand when another object is held in the right hand.

In Neo-Assyrian art these bird-headed “genies,” as they were long described, are now known to be apkallu, “bird-apkallu,” mixed-feature exorcists and creatures of protection created by the god Ea. They traditionally served as advisors to kings. Their association with sacred trees, as they are often portrayed, remains somewhat perplexing. The banduddu (bucket) and mullilu (tree cone) are clearly depicted, in a format which is repeated in Neo-Assyrian art.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/lanpernas2/8606000868/

When a figure does not hold a second object, the hand with which to hold the banduddû is not specified (kusarikku, cf. also text V i 12′; urmahlullû, text VI Col. B:31). Only Ensimah in the divergent “Göttertypentext” (MIO 176 v 21) holds the banduddû in his right hand.

The banduddû bucket is not to be confused with the “flowing vase”, called hegallu, “abundance”, in Akkadian (MIO 1 106 vi 8). In rituals the banduddû was filled with water (cf. CAD : the exorcist imitates Marduk, who, on the advise of Ea, takes water from the “mouth of the twin rivers”, casts his spell over it, and sprinkles it over the sick man: VAS 171i 21ff. (OB) reads: gi ba-an-dug-dug gi a-1á gliš-GAMI -m a šu u m-ti-en / í d ka – min – na a …

Ishtar at far left, with weaponry on her back, knife in hand. She is acknowledging the greeting of a worshipper, with an animal sacrifice in hand.

I am unsure about the divinity portrayed in the center, she is a goddess, the horned headdress confirms it, and she appears to hold the hegallu, a flowing vase, which is synonymous with “abundance.”

My scholarship is yet too meager to hazard a guess about the remaining figures depicted.

What follows is barely readable, but the section ends with: (26′) a ù – m u – e – s ù. In the translation the broken lines have been restored after the late parallels KAR 91 Rev. 1ff. and CT 17 26 64ff. (bilingual): “take the bucket, the hoisting device with the wooden bail, bring water from the mouth of the twin rivers (cf. Falkenstein ZA 45 32 ad CT 17 26 65), over that water cast your holy spell, purify it with your holy incantation, and sprinkle that water over the man, the son of his god”.

The effect of sprinkling the holy water is the “release”(ptr) of the threatened man (cf. Šurpu VIII 41; K 8005+ 33, quoted by Zimmern BBR 157m and CAD B 79b). The connection between “banduddû” and “release” (ptr) may have been reinforced by etymological speculation (dug = patāru).

The gi b a – a n – dug – dug was originally a reed (determinative GI) container (b a – a n, cf. Oppenheim Eames 10, Steinkeller OrNS 51 359) used to carry liquids (VAS 17 1 i 21′, cf. Civil Studies Oppenheim 87); as such it was coated with bitumen: d ug, “to caulk” ((Oppenheim Eames 85, Falkenstein NSGU 3 110).

A b a – a n- dug – dug could be made of metal as well (cf. CAD B 79b). The Neo-Assyrian bucket was occasionally still decorated with an imitation of basket-work design, but in fact apparently made of metal (cf. Madhloom Chronology 110f., Stearns AfOB 15 2544).”

F.A.M. Wiggermann, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts, STYX&PP Publications, Groningen, 1992, p. 66.