Wiggermann Defines the Lamassu

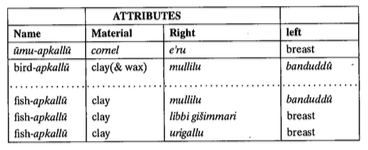

“The limited number of candidates available for identification with e’ru, libbi gišimmari and urigallu enables us to choose a denotation, even when the results of philology are not unequivocal in each case.

The sages and the lesser gods of NAss art share attributes and therefore functions: goat, sprig, greeting gesture, cone, bucket and mace. Both can occur with or without wings.

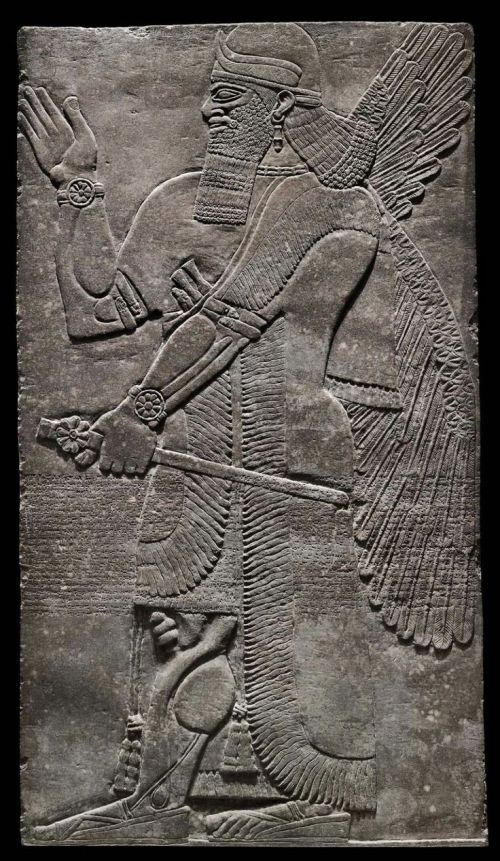

This umu-apkallū makes the iconic greeting gesture with his right hand while holding an e’ru stick in his left.

The tassels of his robe are clear around his ankles, as are bracelets just above his elbows.

Note the detail of the individually feathered wings. The rosette insignia on the e’ru and his wrist is not yet understood. The headdress is a horned tiara, indicative of divinity.

The apkallū of the rituals share properties with some of the gods of the rituals: the šūt kakkī (II.A.3.4) hold the e’ru-stick/mace, the il bīti (II.A.3.8) greets and holds the gamlu-curved staff (attributes also of apkallū in art), the undeciphered intruders of text II Rev. 9f., probably gods since they are made of tamarisk, hold an ara gišimmari (cf. also text IV/1 ii 6’f.; held by apkallū of art), and the šūt kappī, “the winged ones”, of bīt mēseri (III.B.6) hold the e’ru and the libbi gišimmari.

The umu-apkallū at far left has his right hand raised in the iconic gesture of purification and exorcism, but no mullilu cone is present.

The banduddû bucket is present in the left hand. This umu-apkallū wears a horned tiara, indicative of divinity.

The next entity lacks wings, and so is probably not an umu-apkallū. The mace in the right hand could be an e’ru, as it is not yet clear precisely what e’ru means. I do not understand the object in his left hand.

The next entity holds a bowl and the curved staff, known as the gamlu-curved staff. While this entity wears a headdress, it is not horned, and wings are absent, suggesting that it is human rather than umu-apkallū.

The entity at far right wields a curved stick in his right hand, I am unsure how Wiggermann defines it, and I completely stumped by the object in his left hand, which appears to be a ladle. If I had to guess, I would surmise that the entity with the raised bowl is a king, and he is holding an offering which the figure at far right is blessing with the curved stick.

Like the (winged) gods and sages of art (Kolbe Reliefprogramme IIA, VII; above apkallū I and II) the gods of the rituals sometimes kneel (šūt kappī, III.B.6); kamsūtu, “kneeling figures”, probably gods since they are made of tamarisk in ritual II Rev. 11f., occur as well (Ritual II Rev. 11f., Text VI Col. B:25, BiOr 30 178:18).

The designations of these purifying and exorcising gods of the rituals are not names, but descriptions of function or appearance: šūt kakkī, “weapon-men”, it bīti, “god of the house”, šūt kappī, “winged ones”, kamsūtu, “kneeling ones”.

This umu-apkallū holds a feather in his right hand, raised, and holds a small goat in his left hand.

The tassels on his robe are distinct, as are the bracelets on his upper arms, just above his elbows.

The headdress is unknown to me.

Wiggermann appears to favor the ür-term “lamassu” for all such apkallu figures.

Likewise the purifying and exorcising gods of art are not represented as individuals but as indistinguishable members of a group of lesser gods of similar function, holding more or less interchangeable attributes.

Although not an exorcist but an armed door keeper, the nameless god ša ištēt ammatu lān-šu, ” One Cubit” (II.A.3.5), might belong here; the winged goddess holding a bracelet (Kolbe VIII) may be a female member of the same group.

Without definite proof we propose to indentify the nameless exorcising gods of the rituals with the indistinct winged gods of the reliefs.

The “names” distinguish the members of this group according to form or function, but we ought to expect a term identifying these gods as similar lesser gods. The only term available is lamassu (also proposed by Reade BaM 10 36).

In view of the many difficulties surrounding this term (provisionally Foxvog/Heimpel/Kilmer/Spycket RiA 6 446ff.) definite proof would require a separate study.”

F.A.M. Wiggermann, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts, STYX&PP Publications, Groningen, 1992, p. 79.