Eco: The Mixed Systems

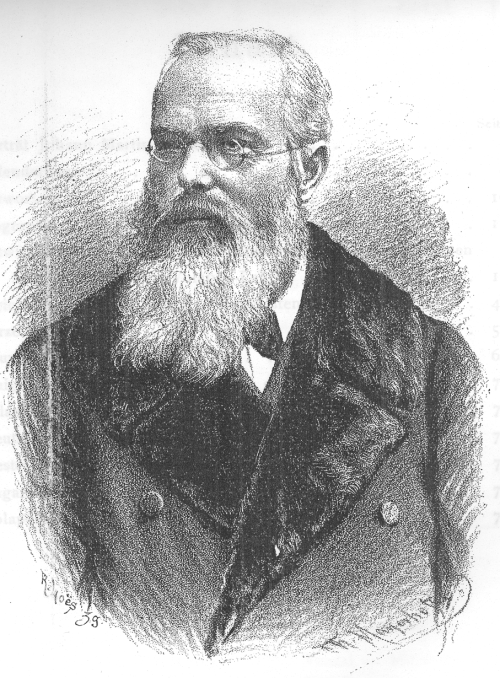

Johann Martin Schleyer (1831-1912), a drawing of the creator of Volapük by Theodor Mayerhofer (1855-1941) in Sigmund Spielmann, Volapük- Almanach für 1888, Leipzig. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“Volapük was perhaps the first auxiliary language to become a matter of international concern. It was invented in 1879 by Johann Martin Schleyer, a German Catholic priest who envisioned it as an instrument to foster unity and brotherhood among peoples.

As soon as it was made public, the language spread, expanding throughout south Germany and France, where it was promoted by Auguste Kerkhoffs. From here it extended rapidly throughout the whole world.

By 1889 there were 283 Volapükist clubs, in Europe, America and Australia, which organized courses, gave diplomas and published journals. Such was the momentum that Schleyer soon began to lose control over his own project, so that, ironically, at the very moment in which he was being celebrated as the father of Volapük, he saw his language subjected to “heretical” modifications which further simplified, restructured and rearranged it.

Such seems to be the fate of artificial languages: the “word” remains pure only if it does not spread; if it spreads, it becomes the property of the community of its proselytes, and (since the best is the enemy of the good) the result is “Babelization.”

So it happened to Volapük: after a few short years of mushroom growth, the movement collapsed, continuing in an almost underground existence. From its seeds, however, a plethora of new projects were born, like the Idiom Neutral, the Langue Universelle of Menet (1886), De Max’s Bopal (1887), the Spelin of Bauer (1886), Fieweger’s Dil (1887), Dormoy’s Balta (1893), and the Veltparl of von Arnim (1896).

Volapük was an example of a “mixed system,” which, according to Couturat and Leau, followed the lines sketched out by Jacob von Grimm. It resembles an a posteriori language in the sense that it used as its model English, as the most widely spread of all languages spoken by civilized peoples (though, in fact, Schleyer filled his lexicon with terms more closely resembling his native German).

It possessed a 28 letter alphabet in which each letter had a unique sound, and the accent always fell on the final syllable. Anxious that his should be a truly international language, Schleyer had eliminated the sound r from his lexicon on the grounds that it was not pronounceable by the Chinese–failing to realize that for the speakers of many oriental languages the difficulty is not so much pronouncing r as distinguishing it from l.

Besides, the model language was English, but in a sort of phonetic spelling. Thus the word for “room” was modeled on English chamber and spelled cem. The suppression of letters like the r sometimes introduced notable deformations into many of the radicals incorporated from the natural languages.

The word for “mountain,” based on the German Berg, with the r eliminated, becomes bel, while “fire” becomes fil. One of the advantages of a posteriori language is that its words can recall the known terms of a natural language: but bel for a speaker of a Romance language would probably evoke the notion of beautiful (bello), while not evoking the notion of mountain for a German speaker.

To these radicals were added endings and other derivations. In this respect, Volapük followed an a priori criterion of rationality and transparency. Its grammar is based upon a declensional system (“house:” dom, doma, dome, domi, etc.).

Feminine is derived directly from masculine through an invariable rule, adjectives are all formed with the suffix –ik (if gud is the substantive “goodness,” gudik will be the adjective “good”), comparatives were formed by the suffix –um, and so on.

Given the integers from 1 to 9, by adding an s, units of ten could be denoted (bal = 1, bals = 10, etc.). All words that evoke the idea of time (like today, yesterday, next year) were prefixed with del-; all words with the suffix –av denoted a science (if stel = “star,” then stelav = “astronomy”).

Unfortunately, these a priori criteria are used with a degree of arbitrariness: for instance, considering that the prefix lu– always indicates something inferior and the term vat means “water;” there is no reason for using luvat for “urine” rather than for “dirty water.” Why is flitaf (which literally means “flying animal”) used for “fly” and not for “bird” or “bee?”

Couturat and Leau noted that, in common with other mixed systems, Volapük, without claiming to be a philosophical language, still tried to analyze notions according to a philosophical method.

The result was that Volapük suffered from all the inconveniences of the a priori languages while gaining none of their logical advantages. It was not a priori in that it drew its radicals from natural languages, yet it was not a posteriori, in so far as it subjected these radicals to systematic deformations (due to an a priori decision), thus making the original words unrecognizable.

As a result, losing all resemblance to any natural language, it becomes difficult for all speakers, irrespective of their original tongue. Couturat and Leau observe that mixed languages, by following compositional criteria, form conceptual agglutinations which, in their awkwardness and their primitiveness, bear a resemblance to pidgin languages.

In pidgin English, for example, the distinction between a paddle wheeler and a propeller-driven steam boat is expressed as outside-walkee-can-see and inside-walkee-no-can-see.

Likewise, in Volapük the term for “jeweler” is nobastonacan, which is formed from “stone” + “merchandise” + “nobility.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 319-21.