Eco: The Egyptian vs. The Chinese Way, 3

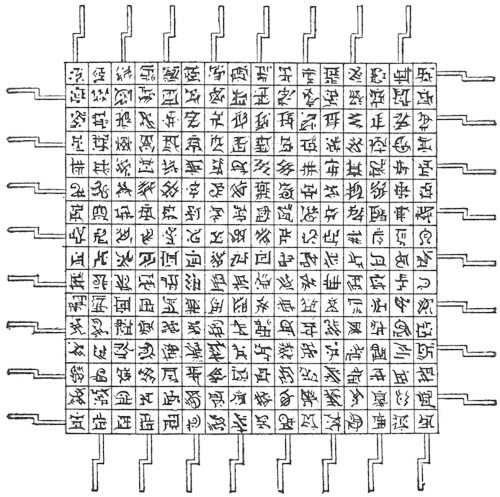

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), Origins of the Chinese Characters, China Illustrata, 1667, courtesy of Stanford University. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“As the debate carried over into the eighteenth century, an increased social awareness and pedagogical attention began to be shown. We catch the traces of this in a tract written for quite different purposes, Diderot’s Lettre sur l’éducation des sourds et muets in 1751.

In 1776, the Abbé de l’Epée (Institutions des sourds et muets par la voie des signes méthodiques) entered into a polemic against the common, dactylological form of deaf-mute speak, which, then as now, was the common method of signing with fingers the letters of the alphabet.

De l’Epée was little interested that this language helped deaf-mutes communicate in a dactylological version of the French language; instead he was besotted by the vision of a perfect language.

He taught his deaf-mutes to write in French; but he wished, above all, to teach them to communicate in a visual language of his own devising; it was a language not of letters but of concepts–therefore an ideography that, he thought, might one day become universal.

We can take for an example his method of teaching the meaning of “I believe,” thinking that his method might also work between speakers of different languages:

“I begin by making the sign of the first person singular, pointing the index finger of my right hand towards my chest. I then put my finger on my forehead, on the concave part in which is supposed to reside my spirit, that is to say, my capacity for thought, and I make the sign for yes.

I then make the same sign on that part of the body which, usually, is considered as the seat of what is called the heart in its spiritual sense. [ . . . ]

I the make the same sign yes on my mouth while moving my lips. [ . . . ]

Finally, I place my hand on my eyes, and, making the sign for no show that I do not see.

At this point, all I need to do is to make the sign of the present [the Abbé had devised a series of sign gestures in which pointing once or twice in front of or behind the shoulders specified the proper tense] and to write I believe.” (pp. 80-1).

In the light of what we have been saying, it should appear evident that the visual performances of the good Abbé might be susceptible to a variety of interpretations were he not to take the precaution of employing a supplementary means (like writing out the word) to provide an anchor to prevent the fatal polysemy of his images.

It has sometimes been observed that the true limitation of iconograms is that, as well as they signify form or function, they cannot so easily signify actions, verb tenses, adverbs or prepositions.

In an article with the title “Pictures can’t say “ain’t,” Sol Worth (1975) argued that an image cannot assert the non-existence of what it represents. It is obviously possible to think of a code containing graphic operators signifying “existence/non-existence” or “past/future” and “conditional.”

But these signs would still depend (parasitically) on the semantic universe of the verbal language–as would happen (see ch. 10) with the so-called universal characters.

The ability of a visual language to express more than one meaning at once is also, therefore, its limitation. Goodman has noted (1968: 23) that there is a difference between a man-picture and a picture of a man.

The picture of a human being can be devised to represent (1) any member of the human race, (2) an individual person so-and-so, (3) a given person on the verge of doing something, dressed in a certain way, and so on.

Naturally the title can help to disambiguate the intention of the artist, but once again images are fatally “anchored” to words.

There have been any number of proposals for visual alphabets, some quite recent. We might cite Bliss’s Semantography, Eckhardt’s Safo, Janson’s Picto and Ota’s LoCos. Yet, as Nöth has observed (1990: 277), these are all cases of pasigraphy (which we shall discuss in a later chapter) rather than true languages.

Besides, they are based on natural languages. Many, moreover, are mere lexical codes without any grammatical component. The Nobel by Milan Randic consists of 20,000 visual lemmas, which can be combined together: a crown with an arrow pointing at a square with the uppermost side missing means “abdication” (where the square stands for a basket); two legs signify “to go,” and when this sign is united with the sign for “with” it means “to accompany.”

We seem to have returned to a sort of simplified hieroglyph which, in any case, will require us to learn a double set of conventions: the first to assign univocal meanings to single signs, the second to assign univocal meanings to sign clusters.

Each of these purely visual systems thus represents (1) a segment of artificial language, (2) endowed with a quasi-international extension, (3) capable of being used in only limited sectors, (4) debarred from creative use lest the images lose their capacity for univocal denotation, (5) without a grammar capable of generating an infinite or unlimited number of “sentences,” (6) unable to express new ideas because every element of expression always corresponds to a predetermined element of content, know in advance.

One could say that there is only a single system, which can claim the widest range of diffusion and comprehensibility: the images of cinema and television. One is tempted to say that this is certainly a “language” understood around the earth.

Nevertheless, even such a language displays certain disadvantages: it has difficulties in presenting mathematical abstractions and philosophical arguments; its alleged universal comprehensibility is problematic, at least as far as its editing syntax is concerned; finally, if there is no difficulty involved in receiving cinematic or televised images, it is extremely difficult to produce them.

Ease of execution is a notable argument in favor of verbal languages. Anyone who wished to communicate in a strictly visual language would probably have to go about with a camcorder, a portable television set, and a sackful of tapes, resembling Swift’s wise men who, having decided that it was necessary to show any object they wanted to designate, were forced to drag enormous sacks behind them.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 173-6.