Eco: New Prospects for the Monogenetic Hypothesis

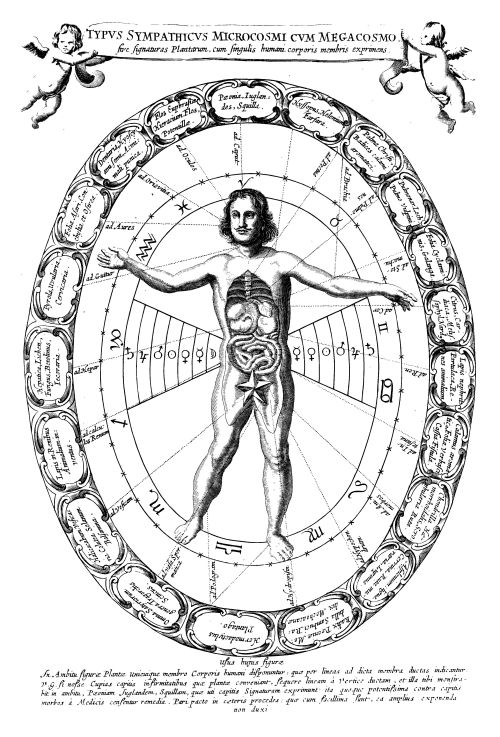

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), frontispiece to Magnes sive De Arte Magnetica, 1641 and 1643 editions, digitized by the University of Lausanne and Stanford University. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“Doubting the possibility of obtaining scientific agreement upon an argument whose evidence had been lost in the mists of time, about which nothing but conjectures might be offered, the Société de Linguistique of Paris 1866 decided that it would no longer accept scientific communications on the subject of either universal languages or origins of language.

In our century that millenary debate took the form of research on the universals of language, now based on the comparative analysis of existing languages. Such a study has nothing to do with more or less fantastic historic reconstructions and does not subscribe to the utopian ideal of a perfect language (cf. Greenberg 1963; Steiner 1975: I, 3).

However, comparatively recent times have witnessed a renewal of the search for the origins of language (cf., for example, Fano 1962; Hewes 1975, 1979).

Even the search for the mother tongue has been revived in this century by Vitalij Ševorškin (1989), who has re-proposed the Nostratic hypothesis, originally advanced in Soviet scientific circles in the 1960s, and associated with the names of Vladislav Il’ič-Svitych and Aron Dolgoposkiji.

According to this hypothesis, there was a proto-Indo-European, one of the six branches of a larger linguistic family deriving from Nostratics–which in its turn derives from a proto-Nostratics, spoken approximately ten thousand years ago. The supporters of this theory have compiled a dictionary of several hundred terms of this language.

But the proto-Nostratics itself would derive from a more ancient mother tongue, spoken perhaps fifty thousand years ago in Africa, spreading from there throughout the entire globe (cf. Wright 1991).

According to the so-called “Eve’s hypothesis,” one can thus imagine a human couple, born in Africa, who later emigrated to the Near East, and whose descendants spread throughout Eurasia, and possibly America and Australia as well (Ivanov 1992:2). To reconstruct an original language for which we lack any written evidence, we must proceed like

“molecular biologists in their quest to understand the evolution of life. The biochemist identifies molecular elements that perform similar functions in widely divergent species, to infer the characteristics of the primordial cell from which they are presumed to have descended.

So does the linguist seek correspondences in grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and vocalization among known languages in order to reconstruct their immediate forebears and ultimately the original tongue. (Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1990: 110).”

Cavalli-Sforza’s work on genetics (cf., for example, 1988, 1991) tends to show that linguistic affinities reflect genetic affinities. This supports the hypothesis of a single origin of all languages, reflecting the common evolutionary origin of all human groups.

Just as humanity evolved only once on the face of the earth, and later diffused across the whole planet, so language. Biological monogenesis and linguistic monogenesis thus go hand in hand and may be inferentially reconstructed on the basis of mutually comparable data.

In a different conceptual framework, the assumption that both the genetic and the immunological codes can, in some sense, be analyzed semiotically seems to constitute the new scientific attempt to find a language which could be defined as the primitive one par excellence (though not in historical but rather in biological terms).

This language would nest in the roots of evolution itself, of phylogenesis as of onto-genesis, stretching back to before the dawn of humanity (cf. Prodi 1977).”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 115-6.