Eco: The Nationalistic Hypothesis, 4

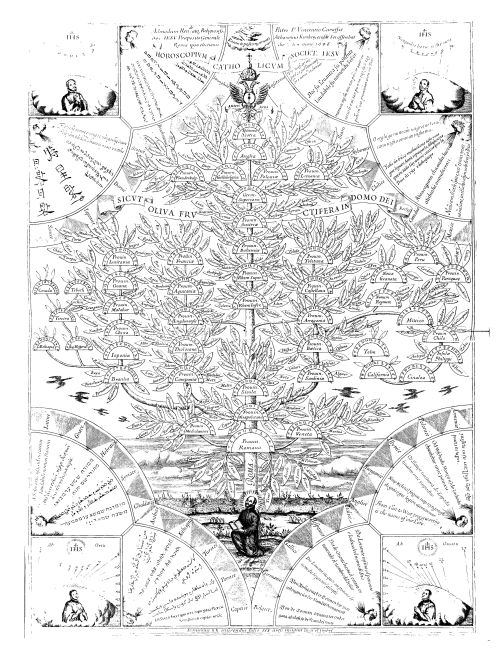

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), Universal horoscope of the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits. Comprising an olive tree as a sundial, the time in each Jesuit province can be read. From Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, 1646, p. 553, courtesy of Herzog August Bibliothek, and Stanford University. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“In the British context, the Celtic hypothesis had naturally quite a different meaning; it meant, for one thing, an opposition to the theory of a Germanic origin.

In the eighteenth century the thesis of Celtic primacy was supported by Rowland Jones, who argued “no other language, not even English, shows itself to be so close to the first universal language, and to its natural precision and correspondence between words and things, in the form and in the way in which we have presented it as universal language.”

The English language is

“the mother of all the western dialects and the Greek, elder sister of all orientals, and in its concrete form, the living language of the Atlantics and of the aborigines of Italy, Gaul and Britain, which furnished the Romans with much of their vocables . . . The Celtic dialects and knowledge derived their origin from the circles of Trismegistus, Hermes, Mercury or Gomer . . . [and] the English language happens more peculiarly to retain its derivation from that purest fountain of languages (“Remarks on the Circles of Gomer,” The Circles of Gomer, 1771: II, 31-2).”

Etymological proofs follow.

Such nationalistic hypotheses are comprehensible in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the larger European states began to take form, posing the problem of which of them was to be supreme on the continent.

In this period, spirited claims to originality and superiority arise no longer from the visionary quest for universal peace, but–whether their authors realized this or not–from concrete reasons of state.

In whatever case, and whatever their nationalist motivations, as a result of what Hegel calls the astuteness of reason, the furious search for etymologies, which was supposed to prove the common descent of every living language, eventually ended by creating the conditions in which serious work in comparative linguistics might become more profitable.

As this work expanded, the phantom of an original mother tongue receded more and more into the background, remaining, at most, a mere regulative hypothesis. To compensate for the loss, there arose a new and pressing need to establish a typology of fundamental linguistic stocks.

Thus, in this radically altered perspective, the search for the original mother tongue transformed itself into a general search for the origins of a given language.

The need to document the existence of the primeval language had resulted in theoretical advances such as the identification and delimitation of important linguistic families (Semitic and Germanic), the elaboration of a model of linguistic descent with the inheritance of common linguistic traits, and, finally, the emergence of an embryonic comparative method typified in some synoptic dictionaries. (Simone 1990: 331).”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 102-3.