Melvin: Divine Knowledge is Transcendent

“Wellhausen understands “good and evil” as a comprehensive term indicating that it is knowledge without bounds. Thus, “knowledge of good and evil” refers to knowledge in general, and the secret knowledge of the workings of nature, the possession of which leads to the development of civilization, in particular.

“Knowledge” in Genesis 3:1–7 would correspond roughly to the “instruction” in the arts of civilization in the Mesopotamian apkallu/culture hero traditions. Wellhausen also notes that progression in civilization correlates with regression in the fear of God in Genesis 1–11, especially in the JE material, giving the entire primeval history a “distinctive gloomy colouring.”

Wellhausen’s view is appealing, but not without significant difficulties. As Gunkel notes, Genesis 3:1–7 says nothing explicit about civilization.

Reading טוב ודע as a merismus (a “merism is a figure of speech by which a single thing is referred to by a conventional phrase that enumerates several of its parts, or which lists several synonyms for the same thing”) is probably correct, but to go beyond understanding this “knowledge” as knowledge in general and connect it with “secret knowledge” of the arts of civilization in such a direct fashion reaches beyond the evidence of the text.

(See the use of טוב and דע in Genesis 31:24, 29 and Isaiah 45:7).

Michelangelo (1475-1564 AD), Sündenfall und Vertreibung aus dem Paradies, Sistine Chapel, Rome.

This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art. The work of art itself is in the public domain because it is outside the copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo_Sündenfall.jpg

Skinner attempts to synthesize the interpretations of Wellhausen and Gunkel by viewing primal humanity as existing in a state of “childlike innocence and purity,” so that the acquisition of “knowledge” corresponds to a maturing and loss of innocence, which would include both sexual awareness and civilizing knowledge.

(Skinner, Genesis, pp. 96–97. One should note that Gunkel does not maintain that Genesis 3:1–7 refers only to sexual awareness, but rather that sexual awareness is the explicit example given in the text of the kind of knowledge which results from eating the fruit.)

What is key for understanding “knowledge” in Genesis 3:1–7 is that it is explicitly connected with divinity, which leads to the second point regarding this passage.

The result of obtaining the knowledge contained in the fruit is that one becomes “like a god.” Thus, the “knowledge” is “divine knowledge”, i.e., the knowledge that is naturally possessed only by gods. This “divine knowledge” would certainly include sexual awareness and the arts of civilization, but it ultimately transcends both.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553 AD), Adam und Eva im Paradies (Sündenfall), Adam and Eve in Paradise (The Fall), 1533 AD.

Held at the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

This work is in the public domain in the United States, and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lucas_Cranach_the_Elder_-_Adam_und_Eva_im_Paradies_(Sündenfall)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Thus, Wellhausen is correct in understanding “good and evil” as a comprehensive term. He is also correct in connecting it with civilization, although it would be more accurate to say that civilization arises as a result of possessing divine knowledge, rather than being the essence of divine knowledge itself.

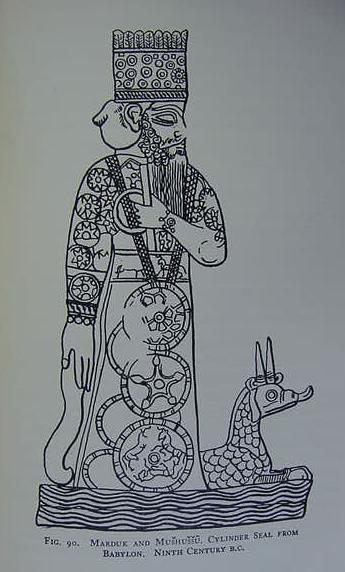

Knowledge was often associated with divinity in the ancient Near East. I have already noted semi-divine transmitters of divine knowledge in Mesopotamia, the apkallus. The name of the Flood hero Atrahasis means “the most wise,” and he is the privileged human recipient of secret knowledge of the decisions of the divine council by revelation from Ea.

(See Brian E. Colless, “Divine Education,” Numen 17 (1970), p. 124.)

Moreover, the life-saving knowledge he receives ultimately leads to his being granted divinity and immortality after the Flood.”

(See the version of the Atrahasis epic from Ugarit, which reads “I am Atrahasis, I was living in the temple of Ea, my lord, and I knew everything. I knew the counsel of the great gods, I knew of their oath, though they would not reveal it to me. He repeated their words to the wall, ‘Wall, hear […] Life like the gods [you will] indeed [possess]” (obv. 6–12, rev. 4 [Foster, Before the Muses, 1:185]).

David P. Melvin, “Divine Mediation and the Rise of Civilization in Mesopotamian Literature and in Genesis 1-11,” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, 2010, pp. 13-4.