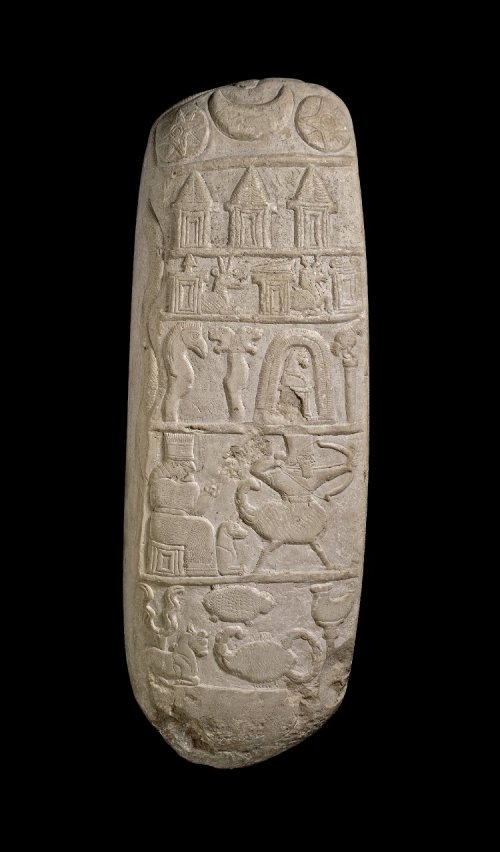

Boundary Stone of Ritti-Marduk (British Museum, No. 90,858)

The accompanying illustration, which is reproduced from the Boundary Stone of Ritti-Marduk (Brit. Mus., No. 90,858), supplies much information about the symbols of the gods, and of the Signs of the Zodiac in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I, King of Babylon, about 1120 B.C.

British Museum number 90858

Description 3/4: Right

Limestone stela in the form of a boundary-stone: consisting of a block of calcareous limestone, shaped and prepared on four sides to take sculptures and inscriptions. It is now mounted on a stone plinth.

Faces B and C each bear a single column of inscription, the lines running the full width of the stone.

The top of the stone and Face D have been left blank, except for the serpent, which has been carved to the left of the emblems on Face A.

Inscribed with a Charter from the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I.

Thus in Register 1, we have the Star of Ishtar, the crescent of the Moon-god Sin, and the disk of Shamash the Sun-god.

In Reg. 2 are three stands (?) surmounted by tiaras, which represent the gods Anu, Enlil (Bel) and Ea respectively.

In Reg. 3 are three altars (?) or shrines (?) with a monster in Nos. 1 and 2. Over the first is the lance of Marduk, over the second the mason’s square of Nabû, and over the third is the symbol of the goddess Ninkharsag, the Creatress.

In Reg. 4 are a standard with an animal’s head, a sign of Ea; a two-headed snake = the Twins; an unknown symbol with a horse’s head, and a bird, representative of Shukamuna and Shumalia.

In Reg. 5 are a seated figure of the goddess Gula and the Scorpion-man.

In Reg. 6 are forked lightning, symbol of Adad, above a bull, the Tortoise, symbol of Ea (?), the Scorpion of the goddess Ishkhara, and the Lamp of Nusku, the Fire-god.

Down the left-hand side is the serpent-god representing the constellation of the Hydra.

The mutilated text of the Fifth Tablet makes it impossible to gain further details in connection with Marduk’s work in arranging the heavens. We are, however, justified in assuming that the gaps in it contained statements about the grouping of the gods into triads.

In royal historical inscriptions the kings often invoke the gods in threes, though they never call any one three a triad or trinity. It seems as if this arrangement of gods in threes was assumed to be of divine origin.

In the Fourth Tablet of Creation, one triad “Anu-Bel-Ea” is actually mentioned, and in the Fifth Tablet, another is indicated, “Sin-Shamash-Ishtar.”

In these triads Anu represents the sky or heaven, Bel or Enlil the region under the sky and including the earth, Ea the underworld, Sin the Moon, Shamash the Sun, and Ishtar the star Venus.

When the universe was finally constituted several other great gods existed, e.g., Nusku, the Fire-god, Enurta, a solar god, Nergal, the god of war and handicrafts, Nabu, the god of learning, Marduk of Babylon, the great national god of Babylonia, and Ashur, the great national god of Assyria.

E.A. Wallis Budge, et al, & the British Museum, The Babylonian Legends of the Creation & the Fight Between Bel & the Dragon Told by Assyrian Tablets from Nineveh (BCE 668-626), 1901, pp. 11-2.

![Illustration: Tablet sculptured with a scene representing the worship of the Sun-god in the Temple of Sippar. The Sun-god is seated on a throne within a pavilion holding in one hand a disk and bar which may symbolize eternity. Above his head are the three symbols of the Moon, the Sun, and the planet Venus. On a stand in front of the pavilion rests the disk of the Sun, which is held in position by ropes grasped in the hands of two divine beings who are supported by the roof of the pavilion. The pavilion of the Sun-god stands on the Celestial Ocean, and the four small disks indicate either the four cardinal points or the tops of the pillars of the heavens. The three figures in front of the disk represent the high priest of Shamash, the king (Nabu-aplu-iddina, about 870 B.C.) and an attendant goddess. [No. 91,000.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00582752_001_l.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration: Tablet inscribed with a list of the Signs of the Zodiac. [No. 77,821.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/015.png?w=500)