Melvin: On the Tower of Babel

“The story of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11:1–9 provides further evidence for the human origin of civilization in the form of city-building. As Theodore Hiebert notes, the story of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11:1–9 is not chiefly concerned with the construction of a tower, but rather with the founding of the city of Babylon.

(Wenham finds it odd that an individual condemned to wander as a nomad would be the founder of city-life, and he suggests that Enoch built the city and named it after his son, Irad. Thus, the name of the first city would have been “Irad”, which is very close to “Eridu”, the oldest city and the first cultural center of the world, where Enki / Ea dwelled (Genesis 1–15, p. 111).

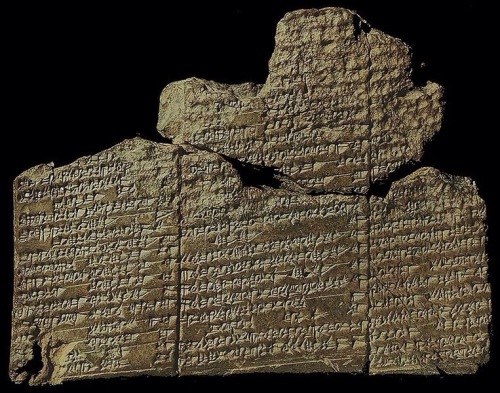

The Birs-i-Numrud, alleged to be the ruined remains of the historical Tower of Babel.

Current dimensions are 150 feet high with a circumference of 2300 ft.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/206180489165185035/

(“The Tower of Babel and the Origin of the World’s Cultures,” JBL 126 (2007), pp. 34–35.)

The biblical text portrays the entire enterprise as an expression of human hubris in the face of the divine command to “fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28; 9:1; cf. Genesis 11:4), and their efforts are met with direct divine opposition.

Here postdiluvian humanity resolves to: 1) build a city and a tower “with its top in the heavens”, and 2) make for themselves a “name”, so that they will not be scattered upon the face of the earth (Genesis 11:4).

Traditional interpretation has viewed this as an act of prideful defiance of Yahweh, although a number of post-colonial interpreters see the story of Babel as an attack on imperial domination.

(See, for example, Christoph Uehlinger, Weltreich und “eine Rede”: Eine neue Deutung der sogenannten Turmbauerzählung (Genesis 11, 1–9) (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1990), pp. 514–58. By way of contrast, Hiebert contends that the account is not about pride and punishment at all, but rather seeks to provide an explanation of the origin of the various cultures of the world (“The Tower of Babel,” p. 31).

Similarly, Walter Brueggemann reads the story as a “polemic against the growth of urban culture as an expression of pride,” specifically, pride before Yahweh.

(Walter Brueggemann, Genesis (Interpretation; Atlanta: John Knox, 1982), p. 98.)

Needless to say, the biblical story of Babel does not depict the city of Babylon as a product of divine action, but rather the story appears to be a polemic against the tradition of the divine origin of Babylon represented in the myth Enuma Elish.

Click to zoom. Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1526/1530-1569), The Tower of Babel, 1563, held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

This work is in the public domain in the United States and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less. This file has been identified as being free of known restrictions under copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_The_Tower_of_Babel_(Vienna)_-_Google_Art_Project_-_edited.jpg

In Genesis 11:1–9, there is no divine assistance in the founding of the city, nor does Yahweh (or any other deity) bless or inhabit it, but rather Yahweh’s intervention to stop the construction by confusing the languages of humanity indicates direct divine opposition to the endeavor.

Westermann’s observations that civilization in Genesis 1–11 is depicted positively insofar as it is 1) actual human progress, without divine assistance as in the Mesopotamian myths, and 2) the working out of the divine blessing of Genesis 1:28–30 (and later 9:1–7) notwithstanding, it is clear that Genesis 1–11 has greatly muted the positive depiction of civilization found in Mesopotamian literature.

(Westermann, Genesis 1–11, pp. 60–61. Similar to Westermann’s is the evaluation of Batto, who reads the Yahwistic account of primeval history as, “the story of a continuously improved creation, which reached its culmination in the final definition of humankind at the conclusion of the flood in Genesis 8.”

Batto reads the J portions of Genesis 1–11 in tandem in the Atrahasis myth as portraits of the attempt of a naïve and inexperienced (and at times bumbling) creator deity to properly define the status and role of humanity. Most of Genesis 2–9 consists of humanity’s attempt to attain divinity by breaking free of the loosely and inconsistently established boundaries established by Yahweh.

At the same time, Yahweh must contend with humanity in order to force them to accept their divinely appointed role as creatures of the soil, only achieving success in Genesis 9:20, when Noah accepts his lot as a “man of the soil” (i.e., a farmer).

Batto compares this reading of Genesis 2–9 with Enlil’s creation of humans for the purpose of serving the gods (e.g., working the ground, digging canals, feeding the gods) in Atrahasis. In both Atrahasis and Genesis, “humankind’s refusal to accept its servant role, grasping at divinity instead” culminates in the flood and finally the concrete definition of humanity as mortal.

It is only with the later Priestly redaction of Genesis 1–11 in the exilic/post-exilic period that Genesis 2–11 becomes the story of “the fall” of humanity from its originally perfect created state in paradise (Batto, “Creation Theology,” 26–38).

Batto’s readings of both Genesis 1–11 and Atrahasis are faulty. Although Batto is correct to point out that the original setting of the creation of humanity in Genesis 2 is a dry, barren wasteland, rather than paradise, it does not follow from this fact that all of the Yahwistic Primeval History is a story of the continued improvement of creation.

Batto makes no attempt to account for how the expulsion of humans from the garden (which has by this time truly become paradise) and the cursing of the soil is an “improvement.” Neither is there as much similarity between the motives for the deity’s sending of the flood in Genesis 6–9 and Atrahasis as Batto maintains.

As Robert Di Vito points out, the argument that the boundary between the divine and the human and humanity’s repeated attempts to achieve divinity are the chief concerns of Genesis 2–11 has been greatly overstated.

The primary sin of the first human couple was that they disobeyed God, and the reason for the flood was the wickedness (especially “violence” חמם) of humanity—not “the violation of ontologically defined boundaries” (“The Demarcation of Divine and Human Realms in Genesis 2–11,” Richard J. Clifford and John J. Collins [eds.], Creation in the Biblical Traditions [CBQMS, 24; Washington, D.C.: The Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1992], p. 50).

While Di Vito goes too far in his denial of the motif of human/divine boundaries in Genesis 1–11—transgression of the boundary between the human and the divine does seem to be an issue in Genesis 3 and in Genesis 6:1–4 (see David L. Peterson, “Genesis 6:1–4, Yahweh and the Organization of the Cosmos,” JSOT 13 [1979], pp. 47–64)—Batto’s attempt to see humanity’s refusal to accept its role as creatures of the soil and servants of the divine reads far too much into the text, while ignoring much of what is there.

Likewise, Batto’s contention that humanity’s refusal to accept its role as servants of the gods led to the flood in Atrahasis is puzzling. Although it is true that the Igigi gods protest against their subjection to labor prior to the creation of humans, there is no hint of such refusal on the part of humanity in the text, and the reason for the flood is not the attempt of humans to obtain divinity, but rather their noisiness (see Atrahasis, I.352–59). There is also no indication that humans sought to obtain divinity, not even Atrahasis, to whom the gods decide to grant immortality after the flood.)

In the Mesopotamian traditions, civilization arises via divine intervention, either directly in the form of a gift bestowed upon humanity, or indirectly through semi-divine mediators. Moreover, in these mythic texts human progress moves along an upward trajectory, from the earliest stages, in which humans are animal-like and incapable of harnessing the elements of nature for their benefit, to civilized life, in which they enjoy the blessings of divine gifts and a more “god-like” status.”

David P. Melvin, “Divine Mediation and the Rise of Civilization in Mesopotamian Literature and in Genesis 1-11,” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, 2010, pp. 9-11.