Melvin: Human Civilization is a Gift of the gods

“At other times, the gods create civilization directly, either through the birth of the patron deities of aspects of civilization (e.g., agriculture) or by means of themes.

(This phenomenon is especially prevalent in Sumerian creation accounts, which often emphasize the importance of agricultural technology by placing the creation of tools prior to and even necessary for the creation of humans (see, for example, The Song of the Hoe [COS 1.157]) and by presenting the development of agriculture as a theogony in which the patron deities of various agricultural technologies are born. See Cattle and Grain in Samuel N. Kramer, Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. (rev. ed.; New York: Harper & Brothers, 1961), 72–73.)

(See Enki and Inanna (COS 1.161). See also Kramer, Sumerian Mythology, 64–68; Bottéro, 238–39.)

In The Song of the Hoe, Enlil invents the hoe, first, in order to prepare the ground for sprouting humans, and second, for humans to use in their work of temple-building.

(In Mesopotamian Creation myths, the origin of humans is usually described in one of two ways. The first is that they are fashioned from clay, usually mixed with the blood of a slain god (cf. Enuma Elish; Atrahasis). The second is that they sprout up from the ground like plants, as is the case here.)

Similarly, in Cattle and Grain the arts of animal husbandry and agriculture are tied to their patron deities, Lahar and Ashnan. In another text, Enki decrees the fates of the cities of Sumer, blessing them and causing civilization to develop.

Batto notes that a number of texts present the earliest humans (i.e., humans prior to the divine bestowal of the gift of civilization) as animal-like. Thus, in Cattle and Grain, early humans walk about naked, eat grass like sheep, and drink water from ditches.

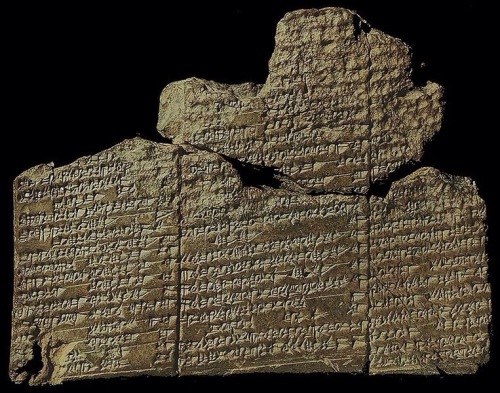

A fragment of The Eridu Genesis.

The earliest recorded Sumerian creation myth is The Eridu Genesis, known from a cuneiform tablet excavated from Nippur, a fragment from Ur, and a bilingual fragment in Sumerian with Akkadian, from the Library of Ashurbanipal dated 600 BCE. The main fragment from Nippur (depicted above) is dated to 1600 BCE.

http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.7.4#

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumerian_creation_myth

It was Thorkild Jacobsen who named this fragment. As he says, “…it deals with the creation of man, the institution of kingship, the founding of the first cities and the great flood. Thus it is a story of beginnings, a Genesis, and, as I will try to show in detail later, it prefigures so to speak, the biblical Genesis in its structure.

The god Enki and his city Eridu figure importantly in the story, Enki as savior of mankind, Eridu as the first city. Thus “The Eridu Genesis” seems appropriate.”

In a footnote, Jacobsen observes, “The tablet was found at Nippur during the third season’s work of the Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania (1893-6) but was not immediately recognized for what it was. The box in which it was kept was labeled “incantation.” Thus it was not until 1912, when Arno Poebel went through the tablet collection, that its true nature was discovered.”

He continues, “Poebel published it in hardcopy … and furnished a transliteration, translation and penetrating analysis …. He convincingly dated the tablet (pp. 66-9) on epigraphical and other grounds to the latter half of the First Dynasty of Babylon.”

“Little further work of consequence was done on the text for thirty-six years—a detailed bibliography may be found in Rykle Borger, Handbuch der Keilschriftliteratur I (Berlin: de Gruyter, p. 411 … but in 1950 Samuel N. Kramer’s translation was published in ANET (pp. 43-4) and again, almost twenty years later, Miguel Civil restudied the text in his chapter on Atra-hasīs (pp. 138-47).

The interpretation here offered owes much to our predecessors, far more than would appear from our often very different understanding of the text.”

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=g5MGVP6gAPkC&pg=PA129&dq=Eridu+Genesis.+Nippur&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CCEQ6AEwAGoVChMI4ImL2PiCxwIVhNWACh01nwD6#v=onepage&q=Eridu%20Genesis.%20Nippur&f=false

Both The Rulers of Lagash and The Eridu Genesis present early humanity as similar to animals in that they slept on straw beds in pens because they did not know how to build houses and also lived at the mercy of the rains because they did not know how to dig canals for irrigation.

Batto concludes that Mesopotamian literature depicts the advancement of early humans as their evolution from a low, animal-like state to a higher, “civilized” state by means of gifts from the gods.

A further illustration of the role of the gods in the rise of civilization in Sumer is the myth Innana and Enki. In this text, Inanna steals the mes (in this case, corresponding to the arts of civilization) from Enki in Eridu and brings them to Uruk, thus transferring civilization to Uruk. The text mentions 94 individual elements of civilization, including:

“… the craft of the carpenter, the craft of the copper-smith, the art of the scribe, the craft of the smith, the craft of the leather-worker, the craft of the fuller, the craft of the builder, the craft of the mat-weaver, understanding, knowledge, purifying washing rites, the house of the shepherd,…kindling of fire, extinguishing of fire….”

Key in this myth is the fact that it is the divine mes, originally bestowed by Enki upon Eridu alone but subsequently transferred to Uruk by Inanna, which give rise to civilization.

What is nearly universal in the Mesopotamian literature, as far as the available texts indicate, is that the source of human civilization is divine, with humans acting primarily as recipients of divine knowledge.

Because of its divine origin and the clear benefits which it provides for humans—at least for those favored humans on whom the gods bestow it—civilization is portrayed in an overwhelmingly positive manner in these texts.”

David P. Melvin, “Divine Mediation and the Rise of Civilization in Mesopotamian Literature and in Genesis 1-11,” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures, 2010, pp. 6-7.