Eco: The International Auxiliary Languages

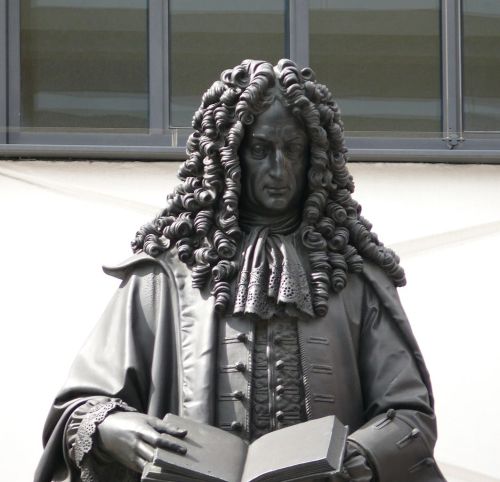

Louis Couturat (1868-1914) & Léopold Leau (1868-1943), Histoire de la langue universelle, Hachette, Paris, 1903, held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and archive.org. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed a revolution in transport and communications. In 1903 Couturat and Leau noted that it was now possible to voyage around the world in just forty days; exactly one half of the fateful limit set by Jules Verne just thirty years before.

Now the telephone and the wireless knitted Europe together and as communication became faster, economic relations increased. The major European nations had acquired colonies even in the far-flung antipodes, and so the European market could extend to cover the entire earth.

For these and other reasons, governments felt as never before the need for international forums where they might meet to resolve an infinite series of common problems, and our authors cite the Brussels convention on sugar production and international accord on white-slave trade.

As for scientific research, there were supranational bodies such as the Bureau des poides et mesures (sixteen states) or the International Geodesic Association (eighteen states), while in 1900 the International Association of Scientific Academies was founded.

Couturat and Leau wrote that such a growing of scientific information needed to be organized “sous peine de revenir à la tour de Babel.”

What could the remedy be? Couturat and Leau dismissed the idea of choosing a living language as an international medium as utopian, and found difficulties in returning to a dead language like Latin.

Besides, Latin displays too many homonyms (liber means both “book” and “free”), its flexions create equivocations (avi might represent the dative and ablative of avis or the nominative plural of avus), it makes it difficult to distinguish between nouns and verbs (amor means both love and I am loved), it lacks a definite article and its syntax is largely irregular . . . The obvious solution seemed to be the invention of an artificial language, formed on the model of natural ones, but which might seem neutral to all its users.

The criteria for this language should be above all a simple and rational grammar (as extolled by the a priori languages, but with a closer analogy with existing tongues), and a lexicon whose terms recalled as closely as possible words in the natural languages.

In this sense, an international auxiliary language (henceforth IAL) would no longer be a priori but a posteriori; it would emerge from a comparison with and a balanced synthesis of naturally existing languages.

Couturat and Leau were realistic enough to understand that it was impossible to arrive at a preconceived scientific formula to judge which of the a posteriori IAL projects was the best and most flexible. It would have been the same as deciding on allegedly objective grounds whether Portuguese was superior to Spanish as a language for poetry or for commercial exchange.

They realized that, furthermore, an IAL project would not succeed unless an international body adopted and promoted it. Success, in other words, could only follow from a display of international political will.

What Couturat and Leau were facing in 1903, however, was a new Babel of international languages invented in the course of the nineteenth century; as a matter of fact they record and analyze 38 projects–and more of them are considered in their further book, Les nouvelles langues internationales, published in 1907.

The followers of each project had tried, with greater or lesser cohesive power, to realize an international forum. But what authority had the competence to adjudicate between them?

In 1901 Couturat and Leau had founded a Delégation pour l’adoption d’une langue auxiliaire internationale, which aimed at resolving the problem by delegating a decision to the international Association of Scientific Academies.

Evidently Couturat and Leau were writing in an epoch when it still seemed realistic to believe that an international body such as this would be capable of coming to a fair and ecumenical conclusion and imposing it on every nation.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 317-9.