Eco: Conclusion

Gustav Doré (1832-1883), The Confusion of Tongues, 1865-68, currently held privately. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“Plures linguas scire gloriosum esset, patet exemplo Catonis, Mithridates, Apostolorum.”

Comenius, Linguarum methodus novissima

“This story is a gesture of propaganda, in so far as it provided a particular explanation of the origin and variety of languages, by presenting it only as a punishment and a curse [ . . . ] Since the variety of tongues renders a universal communication among men, to say the least, difficult, that was certainly a punishment.

However, it also meant an improvement of the original creative powers of Adam, a proliferation of that force which allowed the production of names by virtue of a divine inspiration.”

J. Trabant, Apeliotes, oder der Sinn der Sprache

“Citizens of a multiform Earth, Europeans cannot but listen to the polyphonic cry of human languages. To pay attention to the others who speak their own language is the first step in order to establish a solidarity more concrete than many propaganda discourses.”

Claude Hagège, Le souffle de la langue

“Each language constitutes a certain model of the universe, a semiotic system of understanding the world, and if we have 4,000 different ways to describe the world, this makes us rich. We should be concerned about preserving languages just as we are about ecology.”

V.V. Ivanov, Reconstructing the Past

“I said at the beginning that it was the account in Genesis 11, not Genesis 10, that had prevailed in the collective imagination and, more specifically, in the minds of those who pondered over the plurality of languages.

Despite this, as Demonet has shown (1992), already by the time of the Renaissance, a reconsideration of Genesis 10 was under way, provoking, as we saw, a rethinking of the place of Hebrew as the unchanging language, immutable from the time of Babel.

We can take it that, by then, the multiplicity of tongues was probably accepted as a positive fact both in Hebrew culture and in Christian Kabbalistic circles (Jacquemier 1992). Still, we have to wait until the eighteenth century before the rethinking of Genesis 10 provokes a revaluation of the legend of Babel itself.

In the same years that witnessed the appearance of the first volumes of the Encyclopédie, the abbé Pluche noted in his La méchanique des langues et l’art de les einsegner (1751) that, already by the time of Noah, the first differentiation, if not in the lexicon at least in inflections, between one family of languages and another had occurred.

This historical observation led Pluche on to reflect that the multiplication of languages (no longer, we note, the confusion of languages) was more than a mere natural event: it was socially providential. Naturally, Pluche imagined, people were at first troubled to discover that tribes and families no longer understood each other so easily. In the end, however,

“those who spoke a mutually intelligible language formed a single body and went to live together in the same corner of the world. Thus it was the diversity of languages which provided each country with its own inhabitants and kept them there. It should be noted that the profits of this miraculous and extraordinary mutation have extended to all successive epochs.

From this point on, the more people have mixed, the more they have produced mixtures and novelties in their languages; and the more these languages have multiplied, the harder it becomes to change countries. In this way, the confusion of tongues has fortified that sentiment of attachment upon which love of country is based; the confusion has made men more sedentary.” (pp. 17-8).

This is more than the celebration of the particular “genius” of each single language: the very sense of the myth of Babel has been turned upside down. The natural differentiation of languages has become a positive phenomenon underlying the allocation of peoples to their respective territories, the birth of nations, and the emergence of the sense of national identity.

It is a reversal of meaning that reflects the patriotic pride of an eighteenth century French author: the confusio linguarum was the historically necessary point of departure for the birth of a new sense of the state. Pluche, in effect, seems to be paraphrasing Louis XIV: “L’état c’est la langue.”

In the light of this reinterpretation it is also interesting to read the objections to an international language made by another French writer, one who lived before the great flood of a posteriori projects in the late nineteenth century–Joseph-Marie Degérando, in his work, Des signes. Degérando observed that travelers, scientists and merchants (those who needed a common language) were always a minority in respect of the mass of common citizens who were content to remain at home peaceably speaking their native tongues.

Just because this minority of travelers needed a common language, it did not follow that the majority of sedentary citizens needed one as well. It was the traveler that needed to understand the natives; the natives had no particular need to understand a traveler, who, indeed, had an advantage over them in being able to conceal his thoughts from the peoples he visited (III, 562).

With regard to scientific contact, any common language for science would grow distant from the language of letters, but we know that the language of science and the language of letters influence and fortify each other (III, 570). An international language of purely scientific communication, moreover, would soon become an instrument of secrecy, from which the humble speakers of their native dialects would be excluded (III, 572).

And as to possible literary uses (and we leave Degérando the responsibility for such a vulgar sociological argument), if the authors were obliged to write in a common tongue, they would be exposed to international rivalries, fearing invidious comparisons with the works of foreign writers.

Thus it seems that for Degérando circumspection was a disadvantage for science and an advantage for literature–as it was for the astute and cultivated traveler, more learned than his native and naive interlocutors.

We are, of course, at the end of the century which produced de Rivarol‘s eulogy to the French language. Thus, although Degérando recognized that the world was divided into zones of influence, and that it was normal to speak German in areas under German political influence just as it was normal to speak English in the British Isles, he could still maintain, were it possible to impose an auxiliary language, Europe could do no better than to choose French for self-evident reasons of political power (III, 578-9).

In any case, according to Degérando, the narrow mindedness of most governments made every international project unthinkable: “Should we suppose that the governments wish to come to an agreement over a set of uniform laws for the alteration of national languages? How many times have seen governments arrive at an effective agreement over matters that concern the general interest of society?” (III, 554).

In the background is a prejudice of the eighteenth century–and eighteenth century Frenchmen in particular–that people simply did not wish to learn other tongues, be they universal or foreign. There existed a sort of cultural deafness when faced with polyglottism, a deafness that continues on throughout the nineteenth century to leave visible traces in our own; the only peoples exempt were, remarked Degérando, those of northern Europe, for reasons of pure necessity.

So diffuse was this cultural deafness that he even felt compelled to suggest provocatively (III, 587) that the study of foreign languages was not really the sterile and mechanical exercise that most people thought.

Thus Degérando had no choice but to conduce his extremely skeptical review with an eulogy to the diversity of tongues: diversity placed obstacles in the way of foreign conquerers, prevented undue mixing between different peoples, and helped each people to preserve their national character and the habits which protected the purity of their folkways.

A national language linked a people to their state, stimulated patriotism and the cult of tradition. Degérando admitted that these considerations were hardly compatible with the ideals of universal brotherhood; still, he commented, “in this age of corruption, hearts must, above all else, be turned towards patriotic sentiments; the more egotism progresses, the more dangerous it is to become a cosmopolitan” (IV, 589).

If we wish to find historical precedents for this vigorous affirmation of the profound unity between a people and their language (as a gift due to the Babelic event), we need look no farther than Luther (Declamationes in Genesim, 1527).

It is this tradition, perhaps, that also stands behind Hegel’s decisive revaluation of Babel. For him the construction of the tower is not only a metaphor for the social structures linking a people to their state, but also occasions a celebration of the almost sacred character of collective human labor.

“What is holy?” Goethe asks once in a distich, and answers: “What links many souls together.” . . . In the wide plains of the Euphrates an enormous architectural work was erected; it was built in common, and the aim and content of the work was at the same time the community of those who constructed it.

And the foundation of this social bond does not remain merely a unification on patriarchal lines; on the contrary, the purely family unity has already been superseded, and the building, rising into the clouds, makes objective to itself this earlier and dissolved unity and the realization of a new and wider one.

The ensemble of all the peoples at that period worked at this task and since they all came together to complete an immense work like this, the product of their labor was to be a bond which was to link them together (as we are linked by manners, customs, and the legal constitution of the state) by means of the excavated site and ground, the assembled blocks of stone, and the as it were architectural cultivation of the country.”

(G.W.F. Hegel, trans. T.M. Knox: 638).

In this vision, in which the tower serves as a prefiguration of the ethical state, the theme of the confusion of languages can only be interpreted as meaning that the unity of the state is not a universal, but a unity that gives life to different nations (“this tradition tells us that the peoples, after being assembled in this one center of union for the construction of such a work, were once again dispersed and separated from each other”).

Nevertheless, the undertaking of Babel was still a precondition, the event necessary to set social, political and scientific history in motion, the first glimmerings of the Age of Progress and Reason. This is a dramatic intuition: to the sound of an almost Jacobin roll of muffled drums, the old Adam mounts to the scaffold, his linguistic ancien régime at an end.

And yet Hegel’s sentence did not lead to a capital punishment. The myth of the tower as a failure and as a drama still lives today: “the Tower of Babel […] exhibits an incompleteness, even an impossibility of completing, of totalizing, of saturating, of accomplishing anything which is in the order of building, of architectural construction” (Derrida 1980: 203).

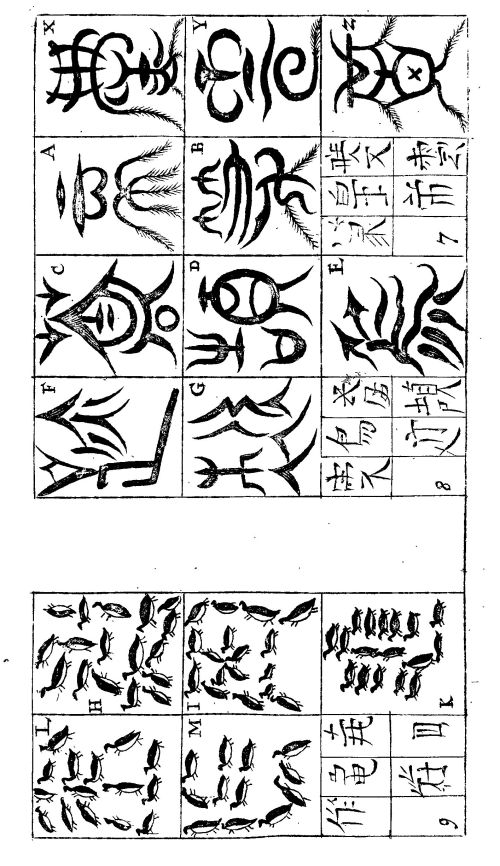

One should remark that Dante (DVE, I, vii) provided a “technological” version of the confusio linguarum. His was the story not so much of the birth of the languages of different ethnic groups as of the proliferation of technical jargons: the architects had their language while the stone bearers had theirs (as if Dante were thinking of the jargons of the corporations of his time).

One is almost tempted to find here a formulation, ante litteram to say the least, of the idea of the social division of labor in terms of a division of linguistic labor.

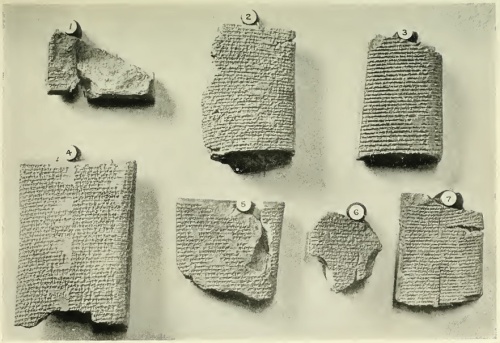

Somehow Dante’s hint seems to have journeyed through the centuries: in his Histoire critique du Vieux Testament (1678), Richard Simon wondered whether the confusion of Babel might not have arisen from the fact that, when the workmen came to give names to their tools, each named them in his own way.

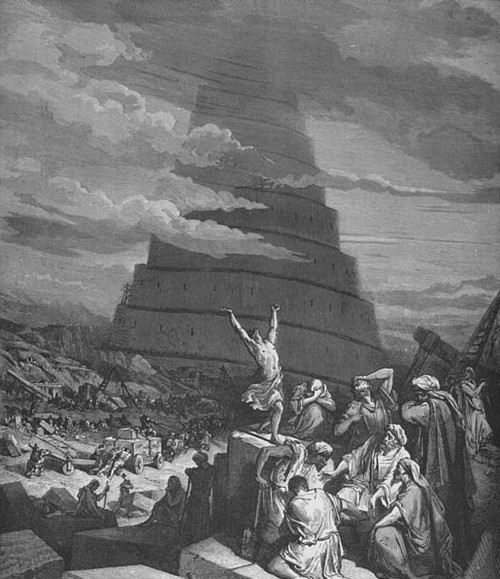

The suspicion that these hints reveal a long buried strand in the popular understanding of the story is reinforced by the history of iconography (cf. Minkowski 1983).

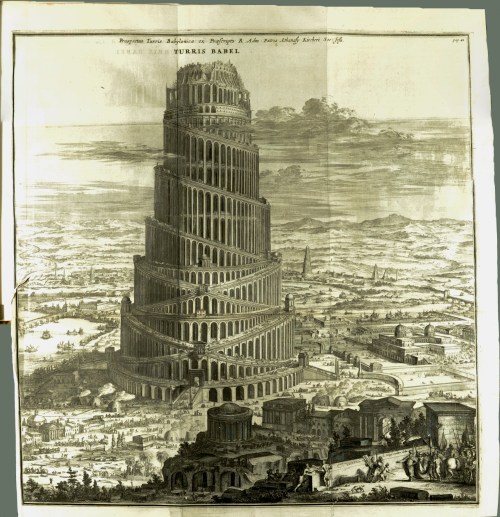

From the Middle Ages onwards, in fact, in the pictorial representations of Babel we find so many direct or indirect allusions to human labor–stonemasons, pulleys, squared building stones, block and tackles, plumb lines, compasses, T-squares, winches, plastering equipment, etc.–that these representations have become an important source of our knowledge of medieval building techniques.

And how are we to know whether Dante’s own suggestion might not have arisen from the poet’s acquaintance with the iconography of his times?

Towards the end of the sixteenth century, the theme of Babel entered into the repertoire of Dutch artists, who reworked it in innumerable ways (one thinks, of course, of Bruegel), until, in the multiplicity of the number of tools and construction techniques depicted, the Tower of Babel, in its robust solidity, seemed to embody a secular statement of faith in human progress.

By the seventeenth century, artists naturally began to include references to the latest technical innovations, depicting the “marvelous machines” described in a growing number of treatises on mechanical devices.

Even Kircher, who could hardly by accused of secularism, was fascinated by the image of Babel as a prodigious feat of technology; thus, when Father Athanasius wrote his Turris Babel, he concentrated on its engineering, as if he were describing a tower that had once been a finished object.

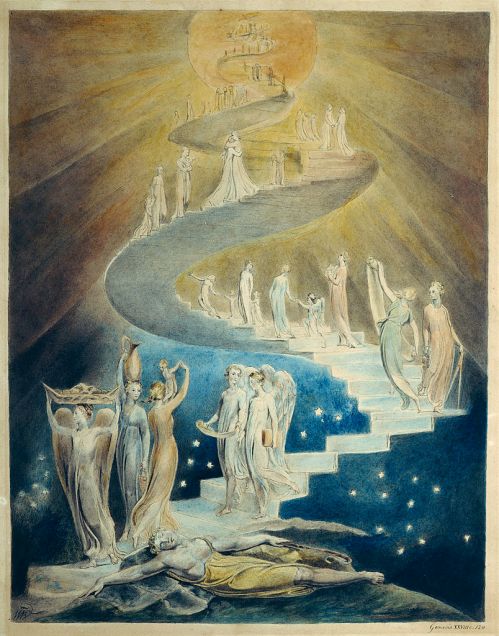

In the nineteenth century, the theme of Babel began to fall from use, because of a lesser interest in the theological and linguistic aspects of the confusio: in exchange, in the few representations of the event, “the close up gave way to the “group,” representing “humanity,” whose inclination, reaction, or destiny was represented against the background of the “Tower of Babel.”

In these dramatic scenes the focus of the representation is thus given by human masses” (Minkowski 1983: 69). The example that readily springs to mind is in Doré’s illustrated Bible.

By now we are in the century of progress, the century in which the Italian poet, Carducci, celebrated the steam engine in a poem entitled, significantly, Hymn to Satan.

Hegel had taught the century to take pride in the works of Lucifer. Thus the gesture of the gigantic figure that dominates Doré’s engraving is ambiguous. While the tower projects dark shadows on the workmen bearing the immense blocks of marble, a nude turns his face and extends his arm towards a cloud-filled sky.

Is it defiant pride, a curse directed towards a God who has defeated human endeavors? Whatever it is, the gesture certainly does not signify humble resignation in the face of destiny.

Genette has observed (1976: 161) how much the idea of confusio linguarum appears as a felix culpa in romantic authors such as Nodier: natural languages are perfect in so far as they are many, for the truth is many-sided and falsity consists in reducing this plurality into a single definite unity.”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 337-44.