Eco: The Gift to Adam

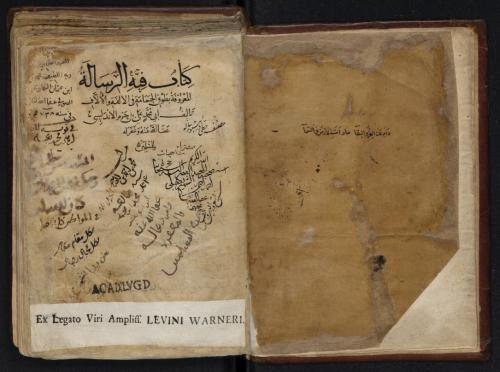

Ibn Hazm (994-1064), The Ring of the Dove (Tawq al-Hanamah), circa 1022, held in the University Library Leiden, Oriental Collections. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“What was the exact nature of the gift of tongues received by the apostles? Reading St. Paul (Corinthians 1:12-13) it seems that the gift was that of glossolalia–that is, the ability to express oneself in an ecstatic language that all could understand as if it were their own native speech.

Reading the Acts of the Apostles 2, however, we discover that at the Pentecost a loud roar was heard from the skies, and that upon each of the apostles a tongue of flame descended, and they started to speak in other languages.

In this case, the gift was not glossolalia but xenoglossia, that is, polyglottism–or, failing that, at least a sort of mystic service of simultaneous translation. The question of which interpretation to accept is not really a joking matter: there is a major difference between the two accounts.

In the first hypothesis, the apostles would have been restored to the conditions before Babel, when all humanity spoke but a single holy dialect.

In the second hypothesis, the apostles would have been granted the gift of momentarily reversing the defeat of Babel and finding in the multiplicity of tongues no longer a wound that must, at whatever cost, be healed, but rather the key to the possibility of a new alliance and of a new concord.

So many of the protagonists in our story have brazenly bent the Sacred Scriptures to suit their purposes that we should refrain ourselves from doing likewise. Ours has been the story of a myth and of a wish. But for every myth there exists a counter-myth which marks the presence of an alternative wish.

If we had not limited ourselves from the outset to Europe, we might have branched out into other civilizations, and found other myths–like the one located in the tenth-eleventh century, at the very confines of European civilization, and recounted by the Arab writer Ibn Hazm (cf. Arnaldez 1981: Khassaf 1992a, 1992b).

In the beginning there existed a single language given by God, a language thanks to which Adam was able to understand the quiddity of things. It was a language that provided a name for every thing, be it substance or accident, and a thing for each name.

But it seems that at a certain point the account of Ibn Hazm contradicts itself, when saying that–if the presence of homonyms can produce equivocation–an abundance of synonyms would not jeopardize the perfection of a language: it is possible to name the same thing in different ways, provided we do so in an adequate way.

For Ibn Hazm the different languages could not be born from convention: if so, people would have to have had a prior language in which they could agree about conventions.

But if such a prior language existed, why should people have undergone the wearisome and unprofitable task of inventing other tongues? The only explanation is that there was an original language which included all others.

The confusio (which the Koran already regarded not as a curse but as a natural event–cf. Borst 1957-63: I, 325) depended not on the invention of new languages, but on the fragmentation of a unique tongue that existed ab initio and in which all the others were already contained.

It is for this reason that all people are still able to understand the revelation of the Koran, in whatever language it is expressed. God made the Koranic verses in Arabic in order that they might be understood by his chosen people, not because the Arabic language enjoyed any particular privilege. In whatever language, people may discover the spirit, the breath, the perfume, the traces of the original polylinguism (sic).

Let us accept the suggestion that comes from afar. Our mother tongue was not a single language but rather a complex of all languages. Perhaps Adam never received such a gift in full; it was promised to him, yet before his long period of linguistic apprenticeship was through, original sin severed the link.

Thus the legacy that he has left to all his sons and daughters is the task of winning for themselves the full and reconciled mastery of the Tower of Babel.”

FIN.

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 351-3.

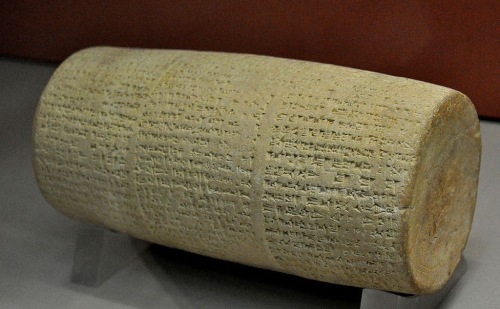

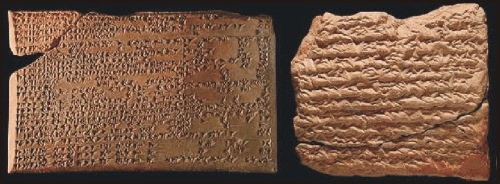

![AM-102 ; No. #1 (K4023) British Museum of London

Tablet K.4023 COL. I [Starting on Line 38] . . . Root of caper which (is) on a grave, root of thorn (acacia) which (is) on a grave, right horn of an ox, left horn of a kid, seed of tamarisk, seed of laurel, Cannabis, seven drugs for a bandage against the Hand of a Ghost thou shalt bind on his temples. FOOTNOTES: [1] - The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 54, No. 1/4 (Oct., 1937), pp. 12-40; Assyrian Prescriptions for the Head By R. Campbell Thompson

http://antiquecannabisbook.com/chap2B/Assyria/K4023.htm](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/k4023-antdiluvian-medical-text.jpg?w=500)