Eco: A Dream that Refused to Die, 2

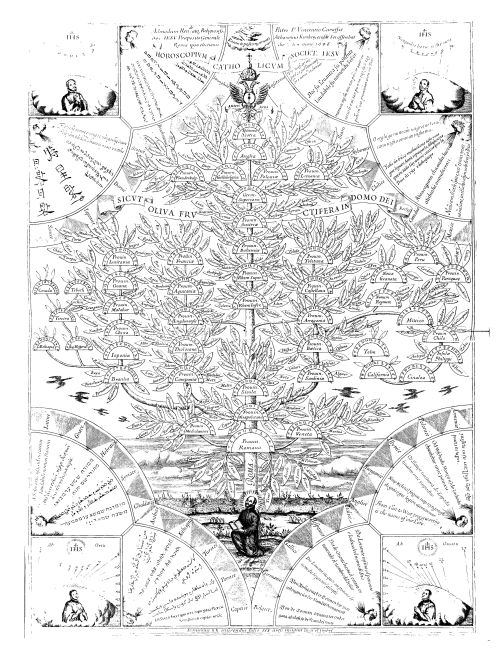

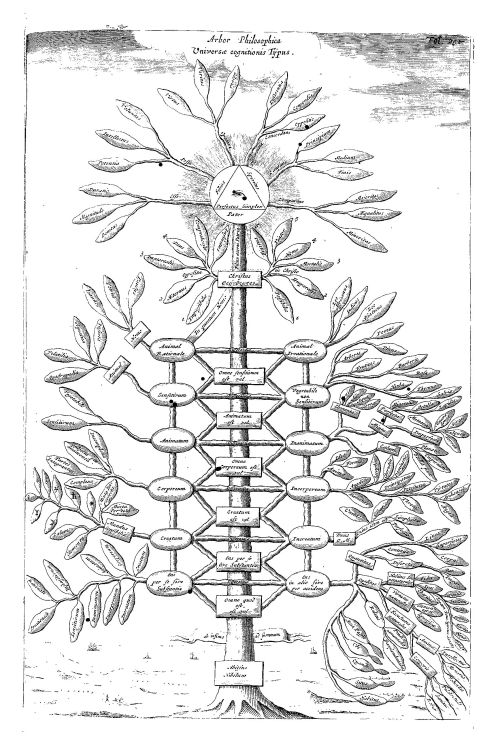

Athanasius Kircher (1602-80), the philosophical tree, from Ars Magna Sciendi, 1669, digitized in 2007 and published on the web by the Complutense University of Madrid. This illustration courtesy of Stanford University. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or less.

“Again apropos of the crusty old myth of Hebrew as the original language, we can follow it in the entertaining compilation given in White (1917: II, 189-208).

Between the first and ninth editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1771 and 1885), a period of over one hundred years, the article dedicated to “Philology” passed from a partial acceptance of the monogenetic hypothesis to manifestations of an increasingly modern outlook in scientific linguistics.

Yet the shift took place only gradually–a series of timid steps. The notion that Hebrew was the sacred original language still needed to be treated with respect; throughout this period, theological fundamentalists continued to level fire at the theories of philologists and comparative linguists.

Still in 1804, the Manchester Philological Society pointedly excluded from membership anyone who denied divine revelations by speaking of Sanskrit or Indo-European.

The monogeneticist counterattacks were many and varied. At the end of the eighteenth century, the mystic and theosophist Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin dedicated much of the second volume of his De l’esprit des choses (1798-9) to primitive languages, mother tongues and hieroglyphics.

His conclusions were taken up by Catholic legitimists such as De Maistre (Soirées de Saint Petersburg, ii), De Bonald (Recherches philosophiques, iii, 2) and Lamennais (Essai sur l’indifférence en matière de religion).

These were authors less interested in asserting the linguistic primacy of Hebrew as such than in contesting the polygenetic and materialist or, worse, the Lockean conventionalist account of the origin of language.

Even today, the aim of “reactionary” thought is not to defend the contention that Adam spoke to God in Hebrew, but rather to defend the status of language itself as the vehicle of revelation.

This can only be maintained as long as it is also admitted that language can directly express, without the mediation of any sort of social contract or adaptations due to material necessity, the relation between human beings and the sacred.

Our own century has witnessed counterattacks from an apparently opposite quarter as well. In 1956, the Georgian linguist Nicolaij Marr elaborated a particular version of polygenesis.

Marr is usually remembered as the inventor of a theory that language depended upon class division, which was later confuted by Stalin in his Marxism and Linguistics (1953). Marr developed his later position out of an attack on comparative linguistics, described as an outgrowth of bourgeois ideology–and against which he supported a radical polygenetic view.

Ironically, however, Marr’s polygeneticism (based upon a rigid notion of class struggle) in the end inspired him–again–with the utopia of a perfect language, born of a hybrid of all tongues when humanity will no more be divided by class or nationality (cf. Yaguello 1984: 7, with a full anthology of extracts).”

Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, translated by James Fentress, Blackwell. Oxford, 1995, pp. 113-5.