Selz: The Debate Over Mesopotamian Influence on Jewish Pre-History is 2000 Years Old

“The reports further continue with the famous account of the downfall of the Persian empire in the same year, after the battle at Gaugamela, north of Mosul (331 BCE).

“On the 11th of that month, panic occurred in the camp before the king. The Macedonians encamped in front of the king. On the 24th [1 October], in the morning, the king of the world [Alexander] erected his standard and attacked.

Opposite each other they fought and a heavy defeat of the troops of the king [Darius] he [Alexander] incited. The king [Darius], his troops deserted him and to their cities they went. They fled to the east.”

As I have learnt from the Swiss philosopher and historian of science, Gerd Graßhoff, these collections of data were systematically made in order to obtain knowledge about the possible connections of various events, and more specifically in order to get information of how one could interfere and prevent an otherwise probable future event.

The Fall of Babylon, John Martin, 1831 CE.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pd/j/john_martin,_the_fall_of_babyl.aspx

John Martin (1789-1854 CE) first exhibited his painting The Fall of Babylon at the British Institution in 1819. He later supervised mezzotint reproductions, hence the date 1831 CE for this print.

Held by the British Museum.

This image is included under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

(I refer to Graßhoff, “Diffusion”; see also idem, “Babylonian Metrological Observations and the Empirical Basis of Ancient Science,” in The Empirical Dimension of Ancient Near Eastern Studies—Die empirische Dimension altorientalischer Forschungen (ed. G.J. Selz with the assistance of K. Wagensonner; Wiener Offene Orientalistik 6, Wien: Lit, 2011), pp. 25-40.)

The Astronomical Diaries are certainly a latecomer within the cuneiform tradition; there is, however no reason to postulate a fundamental change in the methodological attitude of Mesopotamian scholars, at least after the Old Babylonian period.

In comparison to our approaches, “there is no methodological difference for Babylonian scholarship compared to causal reasoning to obtain knowledge about causal regularities with causes indicated by signs. This counts for all sorts of domains of knowledge—from medical, over meteorological, economic to astronomical knowledge.”

(Graßhoff, “Diffusion.”)

Numerous articles and books deal with Enoch and “Enochic literature.” From the viewpoint of a cuneiform scholar, Helge Kvanvig’s book Roots of Apocalyptic: The Mesopotamian Background of the Enoch Figure and the Son of Man must be considered a major contribution.

The Babylonian surroundings of the forefathers of apocalyptic literature, Ezekiel and Deutero-Isaiah, led to the hypothesis that other apocalyptic texts may have their roots in the Babylonian exile.

Be that as it may, the great impact the Babylonian mantic and astronomical tradition had on the growing Hebrew apocalyptic texts remains beyond dispute.

(VanderKam, Enoch and the Growth, pp. 6-15; Robinson, “Origins,” pp. 38-51.)

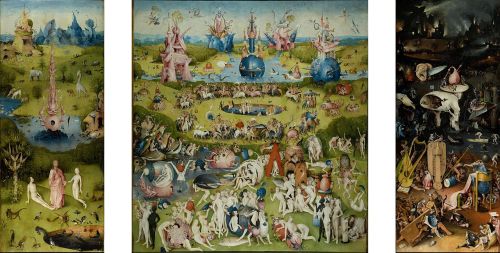

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Earthly Paradise (Garden of Eden).

Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516 CE) painted The Garden of Earthly Delights with oil on panel between 1480 and 1505 CE. This is the leftmost panel of three. It was acquired by the Museo del Prado, Madrid, in 1939.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jheronimus_Bosch_023.jpg

This work is in the public domain in the United States and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less.

Since the times of Flavius Josephus, the first century Jewish historian who also recorded the Roman destruction of the second temple on 4 August 70 CE, the relationship of the Jewish prehistory to the similar traditions of the neighbouring cultures became a pivotal point for all sorts of discussions.

While not very widely distributed initially, the Babyloniaca of Berossos gained increasing influence on the picture of the earlier Mesopotamian history in antiquity, despite the fact that the primary source for all Hellenistic scholarship remained Ctesias of Cnidos (in Caria) from the fifth century BCE.

The interest in Berossos’ work was mainly provoked by his account of Babylonian astronomy, and, in the Christian era, by his record of the Babylonian flood lore.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1480-1505 CE, the complete triptych.

It is in the collection of the Museo del Prado, Madrid.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jheronimus_Bosch_023.jpg

This work is in the public domain in the United States and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less.

(A Hellenistic priest from Babylon, living during Alexander’s reign over the capital (330-323 BCE), that is less than 200 years before the alleged earliest Qumran manuscripts!)

His report of the ten antediluvian kings was paralleled apologetically to traditions from the Hebrew Bible. In this way Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea (circa 260-340 BCE), used the Babyloniaca in order to harmonize the biblical and the pagan traditions, whereas Flavius Josephus used it for Jewish apologetics.

Therefore, the controversial debate over the reliability of biblical stories about the patriarchs and their relation to the mytho-historical accounts of Mesopotamian prehistory have persisted for two millennia.”

Gebhard J. Selz, “Of Heroes and Sages–Considerations of the Early Mesopotamian Background of Some Enochic Traditions,” in Armin Lange, et al, The Dead Sea Scrolls in Context, v. 2, Brill, 2011, pp. 787-9.