More Totemism

“We can learn a good deal about this totemism from the old ideographic representations of the names of the chief deities. They are like fossils, embodying the beliefs of a period which had long passed away at the date of the earliest monuments that have come down to us.

The name of Ea himself affords us an example of what we may find. It is sometimes expressed by an ideograph which signifies literally “an antelope” (dara in Accadian, turakhu in Assyrian, whence perhaps the Biblical name of Terah).

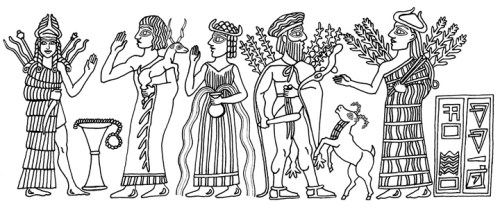

Ishtar is depicted at far left, wearing the horned headdress of divinity, with weapons on her back and a long knife in her hand.

A worshipper presents a sacrificial animal, next to an uncertain goddess depicted with water flowing from her vase.

Ea appears with a fishtail hanging behind him, and an antelope bucking beside him.

I am not certain which goddess appears at far right.

Thus we are told that Ea was called ”the antelope of the deep,” “the antelope the creator,” “the antelope the prince,” “the lusty antelope;” and the “ship” or ark of Ea in which his image was carried at festivals was entitled “the ship of the divine antelope of the deep.”

Ishtar receives the worship of an Amazon. Ishtar stands on a lion, holding a bow with arrows at her back. Her eight-pointed star is atop her head.

Lusty antelopes rear on the right side, perhaps signifying the god Ea.

We should, indeed, have expected that the animal of Ea would have been the fish rather than the antelope, and the fact that it is not so points to the conclusion that the culture-god of southern Babylonia was an amalgamation of two earlier deities, one the divine antelope, and the other the divine fish.

Perhaps it was originally as the god of the river that Ea had been adored under the form of the wild beast of the Eden or desert.

There was yet another animal with which the name of Ea had been associated. This was the serpent. The Euphrates in its southern course bore names in the early inscriptions which distinctly connect the serpent with Ea on the one hand, and the goddess Innina on the other.

It was not only called “the river of the great deep”– a term which implied that it was a prolongation of the Persian Gulf and the encircling ocean; it was further named the river of the śubar lilli, “the shepherd’s hut of the lillu” or “spirit,””the river of Innína,” “the river of the snake,” and “the river of the girdle of the great god.”

In-nina is but another form of Innána or Nâna, and we may see in her at once the Istar of Eridu and the female correlative of Anúna. Among the chief deities reverenced by the rulers of Tel-loh was one whose name is expressed by the ideographs of “fish” and “enclosure,” which served in later days to denote the name of Ninâ or Nineveh.

It seems clear, therefore, that the pronunciation of Nina was attached to it; and Dr. Oppert may accordingly be right in thus reading the name of the goddess as she appears on the monuments of Tel-loh.

Nina, consequently, is both the fish-goddess and the divinity whose name is interchanged with that of the snake. Now Nina was the daughter of Ea, her eldest daughter being described in a text of Tel-loh as “the lady of the city of Mar,” the modern Tel Id, according to Hommel, where Dungi built her a temple which he called “the house of the jewelled circlet” (sutartu).

This latter epithet recalls to us the Tillili of the Tammuz legend as well as the Istar of later Babylonia. In fact, it is pretty clear that Nina, “the lady,” must have been that primitive Istar of Eridu and its neighborhood who mourned like Tillili the death of Tammuz, and whose title was but a dialectic variation of that of Nana given to her at Erech.”

A.H. Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians, 5th ed., London, 1898, pp. 280-2.