Figurines Excavated from the Burnt Palace and Fort Shalmaneser

The most expansive text prescribing the types of figurines is the Aššur ritual KAR, no. 298. After defining the purpose of the ritual as to avert evil from the house, the text begins to prescribe the types of figures to be fashioned and buried at set locations.

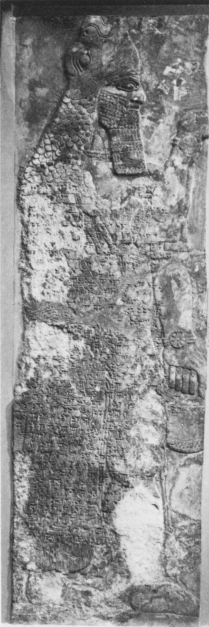

BM 124573, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum. Plate Xa.

This fish apkallū appears to have his right hand raised in the gesture of blessing with the mullilu cone, with the banduddu bucket in his left hand.

It begins with a long passage prescribing wooden figures of seven apkallē “Sages,” from seven Babylonian cities. No such actual figurines appear to exist, nor should we expect any if the prescription were faithfully followed, since timber figurines would have perished.

A bird-apkallū of the Nisroc kind, plate IXb. The figure is too worn to discern what is held in the right hand, while the left hand holds what appears to be a banduddu bucket.

The next passage, however, prescribes apkallū figures with the faces and wings of birds. These are the bird-headed figures (Plate IXb), found appropriately in groups of seven. As well as in the Burnt Palace, a group of such figures was found in Fort Shalmaneser in a late seventh-century context; the excavator believed that the figures were redeposited ninth-century pieces, but they are rather different in style (ND 9518, figures in the round rather than flat-backed plaques) and may in fact date closer to the period suggested by their findspot.

Fish-Apkallū figure, Plate Xb. ND 4118, courtesy of the British School of Archeology in Iraq, photograph by David A. Loggie.

A group of figures of the same type was found by George Smith in the so-called “S.E. Palace,” perhaps a part of the same building as Palace “AB;” the pieces are close in style to the Burnt Palace examples and may date to the late ninth century.

ND 4123 (IM 59291), Plate Xc, courtesy of the British School of Archeology in Iraq. Photograph: David A. Loggie.

The ritual goes on to prescribe a set of seven figures of the apkallē cloaked in the skin of a fish. This type is represented by septenary groups of fish-garbed human figures which vary somewhat from deposit to deposit.

The usual type from the Burnt Palace, thin and fairly flat, sometimes has a fish-head and, on the reverse, a dorsal fin (Plate Xb), but often has no very obvious fish elements, so that the pieces must be identified from others in the same deposit or by comparison with those in other deposits.

Also from the Burnt Palace come some more obvious human-piscine figures of heavy solid clay (Plate Xc). Six examples of this subtype were found, together with a seventh, “leader” (?), figure of the same being but of a very different style: a tall but flat fish-garbed man, the scales and tail indicated on the back by incised cross-hatching and diagonal lines.

ND 7903B. Courtesy of the British School of Archeology in Iraq, photograph by David A. Loggie. Plate Xd.

Over thirty figurines and metal figurine accoutrements were found not buried in boxes but loose in the fill of one of the so-called “barracks-rooms” of Fort Shalmaneser. They would seem to be remnants from disturbed deposits, but evidently reused, since the fish-cloaked figures, of incongruous styles, were nevertheless seven in number.

It is possible, therefore, that the room was a kind of sick-bay, decked out with these prophylactic images. Plate Xd shows one of the types found, rather crudely made but with the line of the fish-cloak evident enough.

It is interesting to note, in this context, that when one of the legs is exposed and set forward on figurines of this type, it is the left one, perhaps foreshadowing an Islamic custom of entering a holy place with the right foot first, but the haunts of the jinn leading with the left.

The fish-cloaked figure is known in Mesopotamian art from the Kassite period, and despite a dearth of extant sculpture was not an uncommon figure in the Neo-Assyrian palace or temple (Plate Xa).”

Anthony Green, “Neo-Assyrian Apotropaic Figures,” Iraq, Vol. 45, 1983, pp. 88-90.